|

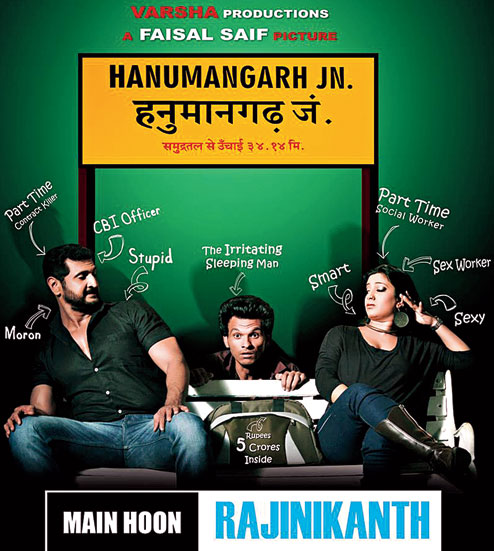

| BRAND EQUITY: A poster of the film Main Hoon Rajinikanth; (right) Sonu Nigam and Sridevi too have sought legal recourse against personality rights violation |

If a comedy called Main Hoon Rajinikanth was about to hit the theatres, was it likely that the south Indian superstar whom it is named after would sit quietly and watch the spoof unfold?

Certainly not. And the real Rajinikanth was quick to move the Madras High Court recently to stop the screening of the film saying it violated his “personality rights”.

The actor contended that the film could defame him and upset his fan base. He also stated that the producer neither approached him nor got his consent — either written or oral — to use his name/ caricature/image/ style of delivering dialogue. “It amounts to causing confusion and deception amongst the trade and public,” he said.

The court took his point and Justice S. Tamilvanan granted an interim injunction and stopped the release of the film using the superstar’s name. (Its director Faisal Saif has since changed its name to Main Hoon Rajini.)

So what exactly are “personality rights”? And why are celebrities invoking them left, right and centre?

Legal experts say that these rights are available to well-known personalities or celebrities to protect them from the unauthorised use of their name, image, signature or persona without permission or compensation.

But personality rights per se are not recognised as distinct legal rights in India, points out Khushal Vibhute, dean, Rajiv Gandhi School of Intellectual Property Law, Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur. They are generally invoked through the Right to Privacy guaranteed by Article 21 of the Constitution or through the Right to Publicity inferred from Article 19.

These rights usually allow for claims of injunction and damages. “The recent Madras High Court ruling in the Rajinikanth case extended this by deeming it to be a civil expression of a celebrity’s fundamental right to live with privacy and dignity, even though he or she is constantly in the public eye,” says Arun C. Mohan, the lawyer who represented Rajinikanth.

In India, personality rights, often called Right of Publicity or Image Rights, have developed primarily through case laws. In 2012, in the Titan Industries Limited vs M/s Ramkumar Jewellers case, trouble arose when Ramkumar Jewellers made unauthorised use of a picture of Amitabh Bachchan and Jaya Bachchan on their billboards — the very same picture that showed the celebrity couple endorsing the diamond jewellery brand owned by Titan. Since the defendant had neither sought permission from the couple nor from the plaintiff to use the image, the Delhi High Court ruled that it had not only infringed the latter’s copyright but also misappropriated the couple’s personality rights. The court said: “When the identity of a famous personality is used in advertising without their permission, the complaint is not that no one should not commercialise their identity but that the right to control when, where and how their identity is used should vest with the famous personality.”

Singer Sonu Nigam too won a case in April this year against another singer, Mika Singh, for the violation of his personality rights. Singh had put up hoardings with pictures of himself and other artistes, including Nigam, performing at an awards function. What irked Nigam was that the hoardings contained an enlarged image of Singh while the images of the other artistes including Nigam were several times smaller. Since Nigam’s picture had been used without his consent, the Bombay High Court ruled that Singh had to pay a compensation of Rs 10 lakh to Nigam for infringing his personality, publicity and image rights.

One of the earliest instances where a celebrity successfully sued those who tried to profit from his personality was when singer Daler Mehndi went to court against gift shops that were selling dolls resembling him. This was in 2001, when his song Tunak Tunak Tun became a huge hit and Mehndi became wildly popular. The Delhi High Court observed that his personality was infused in the dolls and used for commercial gain, which amounted to publicity rights violation.

Recently, actress Sridevi too slapped a legal notice on filmmaker Ram Gopal Verma for using her name in a movie with risque content. A few months back, Amitabh Bachchan spoke out against the unethical use of a deep baritone like his own in the voiceover of an advertisement for gutkha — an association, he claimed, was detrimental to his image.

Clearly, celebrities have become very aware of their personality rights — not only because of the commercial value of their brand but also because of the way its misuse can harm their image. Says Priyanka Khimani, a lawyer who fought the case against Mika Singh, “Today, when celebrities are actively involved in advertisements and endorsements and their images, names and likeness are used on account of their credibility, goodwill and glamour, it is essential for them to be aware of their rights and ensure that their credibility and popularity is not used without their consent.”

But experts say that these rights are not absolute and that there are reasonable restrictions on them. Says Kalyan C. Kankanala, an expert on intellectual property law, “Though celebrities have the right to prevent the commercial exploitation of attributes of their personality, their right is limited by the right of free speech and expression. In other words, a person will not be liable for publicity rights violation if his or her use of a celebrity’s persona amounts to free speech and expression, which includes news reporting, caricature, lampooning, parody, films, songs and so on.”

With celebrities becoming more and more conscious of their personality rights, perhaps it is time these rights were clearly defined in law. Otherwise celebs may soon begin to go to court citing violation of their personality rights every time someone spoofs their larger-than-life ways.