|

|

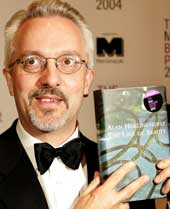

| Hollinghurst: Semi-precious |

The Line of Beauty

By Alan Hollinghurst, Picador, £9.75

?Oh doomful question: is fun, fun?? the irrepressible androgyne and socialite, Stephen Tennant, had once asked Nancy Mitford on a postcard. (?Yes it is,? she had replied promptly.) This was in the Fifties. But Tennant?s question is still at the heart of serious modern novels about male homosexual life in the West. ?Is gayness gay?? they ask in different ways. Or is there not something crass about reducing complex and plural ways of being to the pros and cons of promiscuity? How does one represent in fiction the complexity of the homosexual experience, and the seriousness of what is at stake in it, without letting go of the challenge posed by an access to pleasure that has nothing to do with babies and weddings? And crucially, how does the ?gay writer? remain true to the crossing of the bar (inevitable, if he is any good), when his subject stops being merely ?homosexual experience?, and becomes nothing less than Experience itself ? that ?Jewell?purchased at an infinite rate? ? which takes the reader far beyond questions of sexual orientation and identity?

Alan Hollinghurst ? whose profile includes Oxford English, TLS deputy editorship, four locally successful novels, residence in Hampstead, a distinguished baritone and this year?s Booker ? is well on his way to becoming one of England?s stately homos, to borrow Quentin Crisp?s peerless phrase. Auden, the stateliest after Wilde, called them the Homintern, and resented their attempts ?to secure our Top-Bard as a patron saint?. That ?our? is clever. It plays with his own relationship, as a writer and human being, with Shakespeare: is the point of identification shared Englishness or sexual identity? Auden?s words are from his 1964 introduction to the Sonnets. So his public edginess might have something to do with Parliament having not yet decriminalized homosexual acts between consenting adults. The British law changed in 1967, and Hollinghurst?s writing career ? unlike that of Forster or Isherwood ? began after the public battle had been largely won in the West. Yet The Line of Beauty goes back to a more oppressive time, the Eighties, and to English life under the twin shadows of AIDS, just beginning to be confronted, and Thatcherism, in its fullest glory.

Nick Guest, the novel?s centre of consciousness and a typical denizen of provincial Middle England, has taken his First in English from Oxford and, in the summer of 1983, starts living in London while desultorily working on ?style? in James, Conrad and Meredith. In London, he is a lodger in the Notting-Hill residence (?white stucco and private gardens?) of the ambitious new Tory MP, Gerald Fedden, and his ?distantly foreign? wife, Rachel. Their son, Toby, was Nick?s closest friend at Oxford, and the secret, abiding, but romantically unreciprocated love of Nick?s life. Toby has a brittle, plain-speaking, self-harming sister, Catherine, who goes out with Rastafarians and cab-drivers to outrage her Conservative parents. Nick lives between Toby and Catherine like a ?lost middle child?, with a quietly ?hilarious sense of his own social displacement?. He gets increasingly involved in the ?family?s romance of itself, with its little asperities and collusions that were so much more charming and droll than those in his own family?. (How many more times will Brideshead be revisited?) The inexorable unfolding of Nick?s relationship with the Feddens and the ?frightfully grand people? in their set (including the Iron Lady herself, a cameo Queen among the queens) is the backbone of this novel.

Within and alongside this master-plot, unfold the loves and lusts of Nick?s London life, arranged in a triptych. Part I, ?The Love-Chord? (1983), with its allusion to Wagner?s Tristan Prelude, is about Nick?s affair with Leo (black, working class, reads only Time Out). This is Nick?s ?chocoholic? phase, with another turn of the ?social displacement? screw. The title of Part II, ?To Whom Do You Beautifully Belong?? (1986), refers to the question put by a man to a butler in a country-house in Henry James?s play, The High Bid. This part of the novel is about Nick?s affair with the beautiful Lebanese multi-millionaire, Wani (another Oxford friend), who ?keeps? Nick, gets him addicted to cocaine, and finances the glossy that he ends up editing. Wani embodies chic, trashy, cosmopolitan, sex-and-drugs London. Nick sometimes feels that porn is ?the real deep template? of Wani?s life. But it is while running his hand down Wani?s back that he recalls the ?double curve? of the ?line of beauty? in Hogarth?s Analysis of Beauty (1753): ?the snakelike flicker of an instinct, of two compulsions held in one unfolding movement.? This section ends with the high-camp interlacing of Nick?s dance with none other than Mrs. T herself at the Feddens?s anniversary ball, and his coke-powered threesome in the loo with Wani and Trist?o, the Italian waiter.

The final part, ?The End of the Street? (1987), is where mortality strikes. We learn that Leo had died of AIDS, and that Wani is wasting away with it. Catherine?s godfather publicly embarrasses the Feddens by dying of it. But the Fedden story comes to a climax with the mid-career expos? of Gerald?s affair with his secretary (in classic Tory-party, Boris-Johnson-and-Petronella-Wyatt style), unwittingly brought about by Nick, who is nastily expelled from his lodgings. He has been ?safe?, but goes in for another HIV test. And as he awaits the results, he suddenly discovers the bleak exhilaration of an uncloseted and temporarily unhoused solitude, of ?a love of the world? that is ?shockingly unconditional?.

Hollinghurst is an exceptionally clever and beautifully educated novelist who takes a great deal of care to write eminently quotable, sophisticatedly lascivious prose: ?Leo?s smells were little lessons constantly re-learnt, little shocks of authenticity.? All this exquisite talent and cultural range is deployed to elaborate on the three great preoccupations of upper-class English queenery ? sex, class and beautiful things, and to work endless variations on the ?Post coitum homo tristis? theme. And this is why, in spite of its bejewelled surfaces, the strenuous good taste of its High-Art clutter (sonatas, operas, antiques, paintings, first editions, manoirs in the Dordogne, etc), The Line of Beauty remains a strangely shallow, predictable and provincial novel, mired in a sort of semi-precious Englishness ? a wide-eyed and breathless fascination with frightfully grand people, barely disguised as social parody, that Nick shares with his creator. This is all the more unfortunate because Hollinghurst keeps paying homage to Henry James. ?There is no end/ To the vanity of our calling,? Auden had written in his tribute to the Master at his grave. The ?landscape of Distinction? that Auden?s poem celebrates, with its magnificent reticences and austerities, and its great, trans-Atlantic reach into the tragic heart of Old Europe, becomes, in the hands of this lesser Englishman and aesthete, a wasteland of loveliness and self-congratulatory writing, curiously devoid of any enduring inwardness, although at its better moments, canny, sharp and entertaining, even able, at its best, to capture some of the ?wistful keenness? of being horny and alone in the high London summer.