Is this then the end of our story? Not quite. The Mature Harappan culture (after about 2,500 BC) saw extensive brick construction, cultivation and use of rice and cotton, use of silver and of fixed brick altars, none of which is known to the Rig Veda - though the latter does mention other construction materials (stone, metal, wood), other cereals (barley), other textile fibres (wool, bark, hides) and other precious metals (gold). Further, quite unlike the Mature Indus Valley civilization, Rigvedic society is primarily one of pastoral nomads, only marginally acquainted with forts, crafts and settlements. All this suggests that the Rig Veda could not possibly have been contemporaneous with the Mature IVC.

None of this evidence, however, precludes the Rig Veda having been composed earlier. Some astronomical evidence suggests that the Satapatha Brahmana was composed no later than 2,300 BC - and the Rig Veda of, course, came earlier. At this early date, the Saraswati would certainly have been a majestic river with the Yamuna and the Sutlej as its tributaries, the Indus people may still have been pastoralists who grew some barley and had not yet settled down to irrigated agriculture, to cultivation of rice and cotton and to well-planned brick-built cities.

There remains, however, one major problem with this sequence. The Rig Veda resounds with the sound of horse hoofs and of horse-drawn chariots with spoked wheels. But there is very little archaeological evidence of horses during the Harappan era and none at all earlier. The existence of the Harappan horse is a hotly disputed topic among archaeologists and the source of much personal invective and acrimony. Reports of findings of horse remains at Harappa, Mohenjodaro, Lothal, Kalibangan, Malwan and Kayatha have been ignored by mainstream protagonists or dismissed as unverified. Even the observations of the world-famous archaeozoologist, Sándor Bökönyi, who verified the horse bones at Surkotada have been questioned as "a matter of emphasis and opinion". Figurines found at Mohenjodaro, Lothal, Kunal and Kayatha have been identified as depictions of horses by one school, but as anything but this by another. Terracotta spoked wheels found at Rakhigarhi and Banawali have been associated with horse-drawn chariots by one group but laughed away as representations of spinning wheels by another. The mainstream argument that the evidence in any case is far too scanty to establish the existence of a Harappan horse has been countered by the argument that remains or representations of horses do not become any more abundant after the supposed advent of the Aryans in 1,600 BC - in fact, not until the Mauryas 1,300 years later.

Even if we concede the existence of a Harappan horse, a pre-Harappan horse remains highly elusive. There is no evidence whatsoever of a modern horse or of horse-drawn chariots in India before 2,500 BC. However, it has been claimed that the Rigvedic horse was not the modern horse at all. The latter generally has 36 ribs while the Vedas describe an animal with only 34 (Rig Veda I, 162, 18, Satapatha Brahmana, 13.5). Perhaps, the Vedic horse was the Siwalik horse, which once ran wild across the Himalayan foothills but is believed to have become extinct during the last Ice Age. How, one may well ask, did an extinct animal resurrect itself for the Vedas? A possible answer to this question lies in the fact that "extinction" effectively means "disappearance from the fossil record". Suppose, however, that during the last glaciation, as the ice advanced, the Siwalik horse fled before it, as any sensible and highly mobile animal would, ending up perhaps on the shores of the Arabian Sea where other members of the equine species still run wild. From about 13,000 BC, the ice receded, the sea level rose as the ice melted and the migrant horse was driven inland from its coastal haunts while its remains disappeared in the rising waters. The Rigvedic horse emerges from the sea; it does not descend from the mountain passes.

Counterposed against the traditional tale of Aryan invaders or immigrants from the West with their horses destroying, or at least replacing, the IVC we then have a scenario of an indigenous population with native horses creating the Harappan culture before declining due to natural causes into nomadic pastoralism or being forced to migrate east into the Ganga valley. How does this alternative story square with the traditional model of language diffusion? Sanskrit belongs, as William Jones and Max Müller have established, to the Indo-European language family. And we have long been familiar with the story that the Indo-European languages and their speakers originated somewhere in Asia Minor, Southern Russia or Anatolia and migrated both westward and southeastward, reaching western Europe on the one hand and India on the other. Surprisingly, this account does not necessarily imply that the Aryans entered India during or after the late Harappan era. We may accept that proto-Sanskrit and its speakers immigrated without postulating that they did so only around 1,600 BC or later. Indeed, the British archaeologist, Colin Renfrew, suggests that the Indo-European language ancestral to Sanskrit entered India around 6,500 BC. It arrived in Mehrgarh in Balochistan along with Neolithic farmers carrying the Anatolian invention of settled agriculture. The agricultural community thus created expanded over the millennia, retained its earlier contact with Iran and eventually flowered into the Harappan culture. This account reflects the path and sequence of Aryan movement into India proposed by the Invasion theorists, but not their chronology at all.

We thus have three separate accounts of the people and times of Harappa and of their relationship with the Aryans. According to orthodoxy, the Harappans preceded the Aryans and were either annihilated or cowed into submission by their horse-drawn chariots. According to the other two, the Harappans were the Aryans - but while one claims that the Rig Veda was contemporaneous with the Harappan culture, the other asserts that it represented an earlier phase in Aryan evolution before they had blossomed into the urban sophistication of the IVC. Each account has its problems. The mainstream account cannot explain the end of the Harappans and of their language or the Rigvedic stories of a mighty Saraswati. Both the accounts of an earlier Aryan presence have to contend with what B.B. Lal calls "the problem of the truant horse". The account that makes the Rig Veda contemporary with the Harappan culture needs also to explain the pastoral nomadism of the Rigvedic Aryans as contrasted with the mature urbanism of the Harappans.

We could, of course, have chosen between the accounts had the Indus script been deciphered. If the language disclosed by the script doesn't resemble Sanskrit, the traditional view would have been vindicated, if it is closely related, this view would have dropped out of the picture. Unfortunately, the script has defied century-long efforts at decipherment, so that many feel that it does not represent a language at all but only commonly understood signs like international road signs or identification marks. If this surmise is correct, the IVC would appear, despite its sophistication, to be an illiterate civilization, quite unlike other ancient civilizations, of Egypt or Sumer. It would, however, resemble the Rigvedic culture in which oral transmission was the norm and even the words for "writing" were yet unknown. Also, we could not hope for a clarification of our mystery from this quarter.

An alternative source of clues to the Indus enigma is DNA analysis. Till date, almost all human or animal remains unearthed in the Indus valley have been too severely contaminated in the process for meaningful DNA analysis. However, archaeologists from Deccan College, Pune, have recently exhumed at Rakhigarhi four skeletons for which adequate precautions against contamination have been taken. These skeletons are being DNA tested by Korean forensic scientists soon. Should the tests reveal a close genetic relationship with present day North Indians, the hypothesis that the Harappans were our Aryan ancestors would be strongly reinforced. One of the major mysteries of world history may well be on the brink of resolution.

Concluded

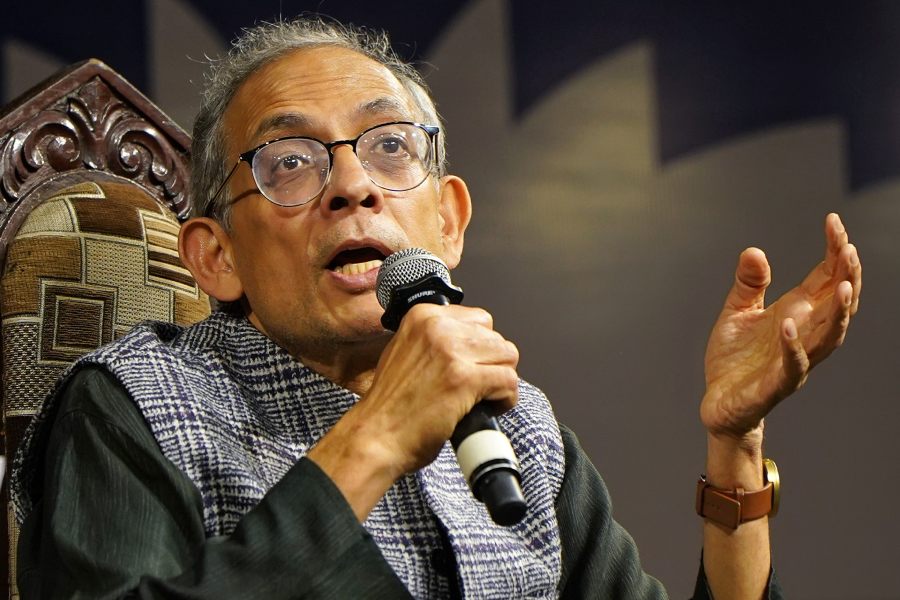

The author is Professor Emeritus, JNU