SHYLOCK IS MY NAME By Howard Jacobson, Vintage, Rs 499

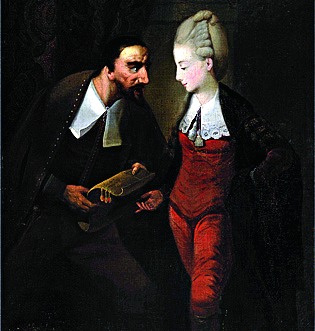

What first comes to mind when one chooses to read Howard Jacobson's Shylock Is My Name, which retells the story of Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice, is what new aspect Jacobson will highlight, or what new question he will raise that has hitherto not been explored. Jacobson has not tried to do either. Rather, he has tried to right an apparent wrong. William Shakespeare's original play never really allowed Shylock to speak. In the few scenes he does appear, he seems capable only of vitriol. The words that the playwright puts in the Jew's mouth were written by a man who could have been an anti-Semite or was at least permissive of the anti-Semitism prevalent in "Judenfrei Elizabethan England". Jacobson introduces not one but two Jews in his novel and allows them to tell their side of the story.

Shylock Is My Name is less of a rereading of the play and more of a sequel to it: what happened after the curtains came down? Did history repeat itself and were the wrongdoers made to account for their karma? At the centre of the plot is Simon Strulovitch, who has a disturbed relationship both with his daughter, Beatrice, and his religion, Judaism. He is not a moneylender but a trader in Anglo-Jewish art and a collector of old Bibles. He is not the modern day Shylock in this novel, but he could be Shylock's descendant living in London. Shylock himself makes an appearance in the story: Strulovitch meets him at a graveyard and invites him home. The book indicates that he is a ghost or a manifestation of Strulovitch's conscience. For instance, when Strulovitch and Shylock happen to be conversing at a restaurant, he notices people staring at them. Strulovitch attributes that to Shylock's loud voice, but people will stare if one speaks Macbeth-like to an empty stool. It is the conversation between the Jew past and the Jew present that takes up most of the space in Jacobson's slim novel.

Strulovitch does not practice Judaism. He does not read the Talmud and yet worries that Jews are on the brink of extermination. He throws away newspapers that do not speak well of the people of his covenant. He also worries that his daughter will marry a "goy" "troglodyte". Strulovitch could be described as a closet Jew. The prejudices that the characters in The Merchant of Venice display have not disappeared in modern times. Hence it is not surprising that Strulovitch distances himself from Jewishness, which he believes is stigmatized, by pretending to be only a secular aesthete.

Shylock, in spite of prejudice, was a proud Jew and had constantly defended his faith and people. He is remembered for the speech in which he says, "I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands... If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die?" In this book, he comes to the rescue of a troubled Strulovitch and encourages him to embrace his Jewish identity. "You secular Jews are more punctilious in your non observance of the law than the Jew of faith is in his performance of it", he explains. "You have as many things to remember not to do... you are, in so many other ways, cut out to be the full Jew... look what a fanatic separator you are... You have a kosher mind." He also tackles the issue of circumcision, a practice central to the male Jewish identity. Strulovitch is told by a psychiatrist that the practice of circumcision jeopardizes the parent-son relationship and that it is barbaric. Shylock explains that circumcision helps boys to get out of their "womb-swoon" - from staying too long in the ideal world of the womb - and realize that life is not idyllic. "We are not born free of loyalties and oaths," he says. "The mohel's knife symbolises what we owe."

Jacobson's portrayal of the other figures in his novel raises disturbing questions. All the Christian characters sound the same. Did Jacobson invest so much of himself in portraying his Shylock and Strulovitch that he intentionally dwarfed the rest? Or is this his way of mocking the bard for depicting all his Christians characters as anti-Semites? Strulovitch's Christians are cardboard figures, capable only of "Jewepithets" and anti-Semitic jokes. They seem mere caricatures of the original characters of the play, and do not work even as satire. In the parent text, the Jew's demand for a pound of flesh has been interpreted as a covert desire to circumcise the Christian Antonio; in this novel the joke is on Antonio - here D'Anton - who, although a proud Christian, is unaware that he has already been circumcised, which he discovers at the end of the novel. This bathetic ending undercuts the seriousness associated with the trial scene. But could it also be the author's way of punishing Antonio for his harsh treatment of Shylock?

Jacobson's women do not fare any better than his Christians. Shylock's wife, Portia, who is extolled as an intelligent woman in the play, is incarnated here as an air-headed Paris-Hilton-like figure. Strulovitch's daughter Beatrice - whose Shakespearean counterpart is Shylock's daughter, Jessica - initally strays and is then redeemed only by dutifully returning to her father.

When Jean Rhys retold Jane Eyre in her Wide Sargasso Sea, she intended to give a voice to Bertha, a mad woman residing in the attic. But in trying to render the dumb vocal, she made the same mistake as Charlotte Brontë and portrayed all her black characters as lascivious and unreliable. Jacobson has gone the same way. In trying to rewrite and not just retell history, and in trying to defend Shylock, he seems to have become biased against his gentile and female characters. The charge of bigotry that is often brought against the playwright can also be brought against the novelist. In order to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the bard, Hogarth Shakespeare has commissioned authors to retell his plays. Shylock Is My Name is a part of the project. But was Jacobson the right choice to retell The Merchant of Venice?