My current research interest causes me some trepidation. The life of one of the earliest Indian members of the Indian Civil Service sounds innocuous enough, especially when it can be shown that India's governance and even political evolution owe something to his quiet initiative. But this very distinction might raise hackles among readers who are averse to fame. It's said that when King Edward VII's tailor complained that the Riviera had gone down socially, the king admonished him, "Don't be silly, we can't all be tailors!"

As a commentator on the contemporary scene, I write about everyone from dukes to dustmen. Dukes couldn't care less when dustmen bask in the limelight. But some dustmen bristle with resentment if they feel attention is lavished on dukes. The reviewer in Desh, for instance, of First Proof: The Penguin Book of New Writing from India accused me of "name-dropping" in my essay, "Didima: The Last Ingabanga". The criticism was amusing for two reasons. To take the second and less important one first, a sudden English phrase in the foremost Bengali literary journal suggested there was no Bengali equivalent of "name-dropping". Does that mean Bengalis steeped in the native culture don't drop names? Or is name-dropping so much the norm that it excites no comment and doesn't even merit a distinctive description?

Social anthropologists would find the first reason - the umbrage the reviewer took because my essay mentioned celebrities - revealing. Some comments expose more the speaker than the subject of comment. In this case, the name-dropping charge meant the reviewer found it impossible to imagine that people he or she (I forget whether the reviewer was male or female) regarded with awe as grandees could be part of someone else's everyday life. What is extraordinary for some can be commonplace for others.

I once witnessed a practical demonstration of this inability to step out of the limitations of one's own skin. My grandmother's unconscious mention of "Rabi babu" provoked an ambitious (then young) Bengali littérateur who happened to be visiting our house that evening to pompous rebuke. "We are trying so hard to teach everyone to say Buddhadev, Saratchandra and Rabindranath..." he began in his mincing Bengali when my grandmother, unable to understand the fuss, cut him short. "But Baba would yell 'Rabi!' whenever he stayed with us in Cuttack or Simultala!" By her reckoning, "Rabibabu" was adequately deferential for a familiar figure from her younger days.

One writes partly for one's own satisfaction and partly for the pleasure of communication. The two are linked, so that personal satisfaction is dimmed when communication fails. That happens usually when writer and reader are not on the same page. Responses often reflect the stratification - perhaps ghettoization would be more accurate - of society. Most of us are content if there is any response at all. It means one isn't writing in a vacuum. But I have long suspected that an English-language newspaper's editorial page has a very limited role in exposing abuses, effecting change and even, perhaps, in establishing communication. Ian Stephens's thunder, in The Statesman, about the Bengal famine had an impact because authority was both English-speaking and suffered from a sense of guilt. Today's tirades about urban public transport or the publicity-seeking farce of Swachh Bharat don't even evoke rebuttal. Authority has become totally insensitive.

It was pleasantly surprising, therefore, when an article in this paper describing the dilatory and negligent postal service in my part of Calcutta brought the Ballygunge postmaster to my flat. The improvement wasn't permanent, but the gesture showed there are still people who care. It was pleasant, too, to note that when I raised the question of municipal taxes with a former commissioner of Calcutta Corporation, he pressed a button and out popped all the relevant documents. It's rarely that an officer of his rank is ready and able to perform such service without summoning clerks and peons. Like the postmaster, he was a short-lived exception. The next commissioner was firmly embedded in pride and prestige.

It would have been the peak of professional satisfaction if irate auto drivers had mobbed me when I wrote about my auto rides to Metro stations. That would have meant that this particular genre of journalism is not yet totally irrelevant. It would have indicated an egalitarian society in which knowledge of English is a unifying and not divisive factor, and where reading English-language newspapers isn't the indulgence of an infinitesimally small percentage of the public. I had to be content, instead, with a friend's telephone call from Delhi expressing surprise that I should ride autos.

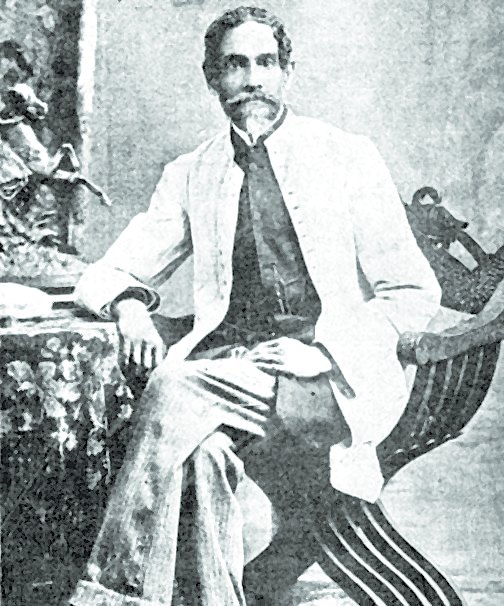

More ambitious topics can have critics sharpening their machetes. Bihari Lal Gupta's plea for justice resulted in the Ilbert Bill to establish parity between Indian and British magistrates. The bill was a watered-down version of the original measure and a victory for its British opponents. But, as the Oxford historian, Margaret MacMillan, says, the diehards who won a battle lost the war. Their victory had an unforeseen result. "Indian nationalists who, up till then, had confined themselves to the politest of requests for the mildest of reforms watched and learned from the storm. They learned how to organize an effective protest; they discovered that the Government of India did not like a fuss; they saw the futility of appealing to opinion in Britain. Shortly after the Ilbert Bill agitation, the Indian National Congress held its first meeting. Indian nationalists went on being polite but they also began to make larger and firmer demands."

The Indian Association and the National Conference to which Gupta's childhood friend and former ICS colleague, Surendra Nath Banerjea, had already invited delegates from all over north India, provided the link between the Ilbert Bill agitation and the INC. Banerjea has told his story in several volumes of speeches and autobiography. The third member of the ICS trio, Romesh Chunder Dutt, was even more prolific. Gupta alone left no record of his doings. It's almost as if he deliberately followed the motto his cousin, Pramathalal Sen, Keshub Chandra Sen's nephew, inscribed in the students' hostel he set up in Harrison Road, "Seek to be Unknown".

Not only is he unknown but some of what little is known is incorrect. Although S. Gopal places the Ilbert Bill in "the highest reaches of political morality and statesmanship" in his admirable work, The Viceroyalty of Lord Ripon 1880-1884, he mistakenly suggests "the government could not shrink from a remedy" after Gupta "proved he was a victim of unjust discrimination." Actually, Gupta wasn't a magistrate when he demanded equality as a matter of principle. The beneficiaries were Dutt and the first Indian in the heaven-born service, Rabibabu's "Bhai Meja Dada", Satyendranath Tagore.

Writing about them can be called name-dropping. Since Gupta was my great-grandfather, it will undoubtedly provoke fresh charges of nepotism. But it is ignorantly shortsighted to ignore people in the public domain because they are family. There were many reasons for punishing Sanjay Gandhi but, as his mother rightly observed, being her son wasn't one of them. My son's book launch fracas I described ("Instructive scuffle", July 18) was widely reported on the internet and media because certain issues were at stake. Intelligent readers understood that as well as the meaning of the "full disclosure" admission at the start of my article. Anyone who is at all familiar with India's socio-economic history (or social scene) also knows that the first Indian head of the Inchcape empire was much more than either a boxwallah or royalty.

This is not an apology. It's an explanation. Also an appeal to more knowledgeable readers for any details they might have, no matter how trivial, about Bihari Lal Gupta's life, career, family and friends. I would be most grateful for information sent to blgupta1849@gmail.com.