The unquiet ones: A history of Pakistan cricket By Osman Samiuddin, HarperSport, Rs 799

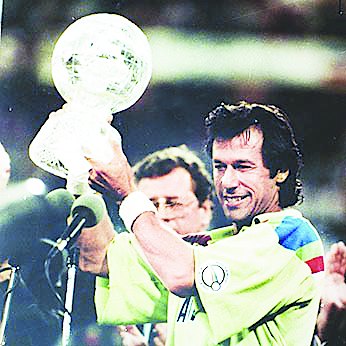

Two stories nicely validate the conundrum of Pakistani cricket for me, a special place where the sublime strikes a fine balance with the ludicrous, the bewakoofi with the jaazba and the izzat. A friend, who would know, related the first of the stories. Wasim Akram is once said to have told him how Pakistan was up against the wall in some Test match; Wasim had come in, not having done much with the bat in the series, but at the other end Inzamam was his usual, blasé, brilliant self. So with the last ball coming up, Wasim walked down to Inzi and told him to just tap the ball and run and the 'farming' would be accomplished. Inzi nodded; the last ball was bowled and even before Inzi had played it, the very athletic Wasim was at Inzi's end. The ball shot to square leg off a superbly executed flick but Inzi had not budged. Wasim slid to a halt, with both batsmen at one end. Inzi looked at Wasim and said, 'Wasim bhai, aap yahan?' The other story is darker. Osman Samiuddin tells it in his book. On the eve of the 1992 World Cup, Pakistan had flown in early but found itself beset with problems; fitness, lack of form, dissensions, a captain who himself was nursing a tired body. And the Australia match was coming up. Imran sensed the quantum of despair and lined up his team; he was wearing his special T-shirt with the springing tiger. Imran was, at the best of times, an avuncular sort, someone who spoke in short, staccato sentences. He asked each one, 'Is there a more talented player than you, in this world? Pakistan will win this World Cup.' It was abrupt and up front. The fact that Inzi and Wasim and a re-energized team worked their magic and proved their iconic captain right is World Cup history. Then, at the presentation, Imran dedicated the Cup to his cancer hospital; the team was left out in his speech. Many were astounded; more importantly, it left a trail of bitterness amongst all who were involved in the game in Pakistan. Many years later, Imran chided himself for his lack of grace. I think Osman Samiuddin also believes that such incidents serve the purpose of pinning down the contrariness more effectively than a bucketful of words and phrases offered as analyses and often inserts anecdotes and quirky comments to make his point. For example, he quotes Imran, handing over the ball to a very jittery Aquib Javed with Viv Richards chewing gum at the striker's end, saying, chillingly, ' Maro b*****d ko bouncer'; Aquib, the teen neophyte, said later that he felt an uncontrollable adrenaline rush as he began his run up. Not to imply, though, that Samiuddin's book deals only in insta-prints and trivialities; his research is remarkably diverse and deep, and he uses it all to very good effect, highlighting the themes of jaazba and izzat which have rescued Pakistani cricket time and again from the pit of chaos.

Save for a few deflections and time warps, he follows a fine chronological order of things; the beginnings of club and college cricket, pre and post '47; the first few national teams, the early tours, the historic Oval victory of 1954 rising like a phoenix out of the bitter ashes of a simmering dispute between captain and star players; the slow, troubled beginnings of the BCCP, of radio and, later, television coverage, which was seen by those who ran the country as a 'diversionary narcotic'; the abysmal 1960s and the glorious 1990s; the friction within and on the periphery of the teams, mainly the Lahore-Karachi divide that just refused to die, fuelled by nepotism and abysmally inept political interference. Samiuddin writes that when spinner Haseeb Ahsan was suspected of chucking, the legendary Crawford White of the Daily Express queried team manager Ghaziuddin 'Gussy' Haider about the chucking tag attaching to some of his team's spinners. 'What do you mean some? All my bowlers are chuckers and bloody good ones,' 'Gussy' thundered. Haider, a polo man, had no idea what White was talking about. And, of course, the captaincy carousel; from the Oxford educated, upper class A.H. Kardar ('Kardar was an authority figure,' the fabled commentator-sports journalist of Pakistani cricket, Omar Kureishi, memorably commented, 'unfortunately the authority he believed in was his.') to Imran Khan, who was more NWFP warlord than Oxonian, with bits of the gully-smart Miandad and the tortured Javed Burki thrown in. Samiuddin's book is inspired, when he traces the black comedy of Pakistan's captaincy woes, particularly when youngsters were elevated to that position because, as he says, 'this always meant ( sic) that there is turmoil in the team and/or the management... the results under him are a reflection of that turmoil.' But what is significant is how the team always rose above these issues, in one more example of the intriguing balance we talked about at the beginning. In essence, 'administrative degeneration' habitually called for panic stations and in one critical instance, 'Kardar met Pirzada, Pirzada met the players, Pirzada met the PM, Kardar met the players, the PM met the players, Kardar met the PM.' Cricket suffered telling blows, but not more than Bangladeshi cricket, according to an incensed Samiuddin, 'Administratively short-changed, politically suppressed, culturally ignored, linguistically repressed and economically exploited, it (East Pakistan) looked a poor picture... It could not but help seep through to cricket.'

Samiuddin is a well rounded cricket journalist and his professional stimuli mark out his book; scrupulous research, orderliness of subject matter, basic no fuss reportage, respecting his readership and so on. Thus, clearly outlined segments are reserved for the movers and shakers of Pakistani cricket with the occasional joker in the pack thrown in for effect, and I would leave you to decide who's what. Yet, I have two problems with his book; one on subject matter and the other on style. First, I think the book misses out appreciably by shying away from paralleling the chronicles of other cricketing nations, at least those of India and Sri Lanka, the sub continental brothers. Basically, were the fault lines of Pakistani cricket missing elsewhere, and if not, how did they cope? Second, Samiuddin's highly readable style, which shows up frequently in his description of personalities and perils, the dynamics of the spinning or the swinging ball and the defiant riposte, loses its way as it tortuously negotiates, at unnecessary length, the match-fixing and ball-tampering episodes, but these are small irritants in an otherwise finely told tale, particularly so because we know how difficult it is to play with a straight bat when there are multiple demons in the pitch.