|

|

Government changes in south Asia often remind us how dissimilar are the political cultures and practices in the subcontinent, especially in India and Pakistan. This week’s change in government in Islamabad, however, has been different. It has eerie similarities with the recent political changes in New Delhi.

Pakistan’s new prime minister, Chaudhry Shujaat Hussain — howsoever interim he may be — is the scion of Pakistan’s third most important political dynasty after the Bhuttos and the Sharif brothers. Like the Nehru-Gandhis on the other side of the border, but quite unlike India’s foremost political dynasty in background or upbringing.

Chaudhry Shujaat’s father and the political deity of the family, the late Chaudhry Zahur Elahi, was a mere assistant sub-inspector of police until he realized that serving the “land of the pure” through politics was his real calling. He became what his biographers unanimously call a “seasoned parliamentarian”. Amnesty International named him a “prisoner of conscience” some time before he was murdered in 1981. But along the way, the assistant sub-inspector-of-police-turned-politician also became one of the richest men in Pakistan with ownership of textile factories, sugar mills and agricultural farms.

After the senior Chaudhry’s assassination, the now-incoming interim prime minister donned the joint political family’s leadership. His political instincts and cunning surpassed that of his father. After Pakistan’s elections, carefully choreographed by Pervez Musharraf in October 2002, Chaudhry Shujaat was the natural choice for prime ministership.

He became president of the “King’s party”, as the Pakistan Muslim League (Qaid-e-Azam) is derisively known in Pakistan, because it was formed by defectors from Nawaz Sharif’s party to support “King” Musharraf in acquiring the fig-leaf of democratic respectability. Chaudhry Shujaat was elected leader of the parliamentary party, making him the obvious choice for prime ministership. Above all, Chaudhry Shujaat showed Musharraf how good he was at splitting his opponents and creating a majority in the national assembly. Therefore, everyone expected Chaudhry Shujaat to be the prime minister of Pakistan in November 2002.

Then, out of the blue, he addressed the nation on October 24 that year because he believed he owed the nation an explanation on why he was renouncing the prime ministership of Pakistan when “I have been elected as the parliamentary leader of the single largest party”. He acknowledged that “there has been unrelenting pressure from across the nation and from all quarters that I, being the natural and logical choice to head the new government” should become prime minister.

“My family elders saw politics as a vehicle for public service and not for the naked pursuit of power…Today, Pakistan stands at the crossroads. It is time for wisdom and sacrifice. If the larger national interest requires a personal sacrifice, then so be it. For the sake of Pakistan, I am giving up the right to be prime minister of Pakistan when the tradition in the past has been to sacrifice Pakistan for personal political power,” he told a stunned Pakistan. “Lust for power led to the break-up of Pakistan in 1971 and in the continuing jump from crisis to crisis… Make no mistake, I treat this as an amanat. The sole consideration will be the supreme national interest of Pakistan … I hope to see a new dawn of decency and democracy in Pakistan, Inshallah.”

More often than not, Pakistan has followed India’s lead in many areas — especially after the end of the Cold War and the collapse of socialism — for reasons that are geographic, economic and geo-political. But as Pakistan gets a new government, and researchers and analysts across the world dig up details about its new prime minister — albeit interim — there will be a realization in foreign offices across the world that for a change, the political process in India after the last elections followed that of Pakistan after its October 2002 poll. Sonia Gandhi’s renunciation of prime ministership in her speech to the Congress parliamentary party on May 18 was eerily similar to Chaudhry Shujaat’s speech to the nation on October 24, 2002.

But the recent similarities in the political processes of India and Pakistan do not end there, although, in some respects Pakistan is following India’s lead. In May, India elected an economist who does not fit the traditional mould of a politician as its new prime minister. Pakistan will do the same soon, once its finance minister, Shaukat Aziz, now a senator, is elected to the national assembly: Pakistan’s constitution does not allow a member of the upper house to become prime minister. Like Manmohan Singh a decade ago, Aziz has been instrumental in reforming Pakistan’s economy under Musharraf. No one talks of Pakistan any more as a failed state in economic terms, and the credit for this goes largely to Aziz.

Another similarity in the political process, though, is not a source of comfort for Indians. About 10 days ago, The Economist published a story about India, which must have acutely embarrassed a regular Indian reader of that magazine: the prime minister, Manmohan Singh. The story is titled, “India’s tainted ministers: the boys from Bihar”, and chronicles, with more kindness than they deserve, the allegations of corruption, crime and abuse of power by Laloo Prasad Yadav and his ilk.

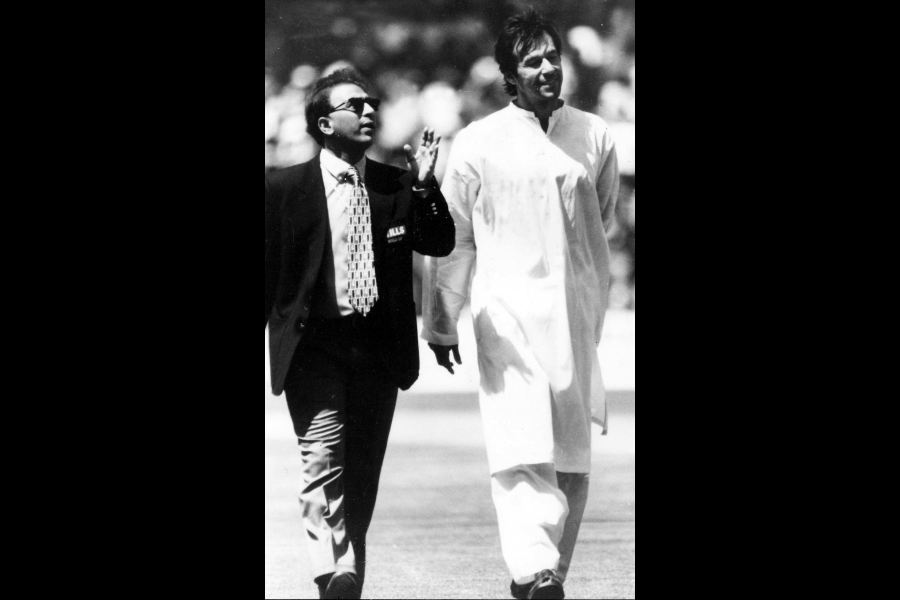

Chaudhry Shujaat and his family could easily match Laloo and his fellow politicians on this score. A documented example of the abuse of power by Chaudhry Shujaat’s family was brought to Musharraf’s attention by the cricketer-turned-politician, Imran Khan, nearly two years ago. Nothing happened.

The case cited by Khan involves a loan of Rs 22.792 million written off by Pakistan’s Muslim Commercial Bank four years ago. According to Khan, the State Bank of Pakistan was allegedly involved in a similar write-off of Rs 218.598 million. Both loans were given to Punjab Sugar Mills, where Chaudhry Shujaat, his uncle Chaudhry Mansoor Elahi and cousin Chaudhry Pervez Elahi, the chief minister of Punjab, were all directors. A case filed in Lahore high court by Mian Sajid Pervez, president of Khan’s Tehrik-i-Insaf party, alleged a similar loan write-off by the National Bank of Pakistan to the tune of Rs 37.987 million.

Under Pakistani law, if a politician, his spouse or any dependents have not repaid any bank loan of Rs 2 million or above, he would be disqualified from being elected to national or provincial assemblies. It is a testimony to the immense clout of the Chaudhry family that one of its defaulting members has thrived as Punjab’s chief minister while another has become the country’s prime minister. Meanwhile, typifying subcontinental politics, there is no shortage of new, emerging dynasties in Pakistan.

Waiting in the wings for Aziz to either fail or become expendable is the trio of sons of former generals. They are Ejaz-ul-Haq, son of Zia-ul-Haq, Gohar Ayub, son of Ayub Khan, and Humayun Akhtar, son of General Akhtar Abdur Rehman, Zia’s ISI chief who was killed along with him in a plane crash. All three sons are suspected by Pakistan’s National Accountability Bureau of having stashed away billions of dollars abroad in ill-gotten wealth, obviously bequeathed to them by their fathers.

Of these, Humayun Akhtar, a former commerce minister, is said to be Musharraf’s favourite, who missed being prime minister this time because Chaudhry Shujaat wanted the job and preferred Aziz to succeed him when he goes abroad again shortly for medical treatment.