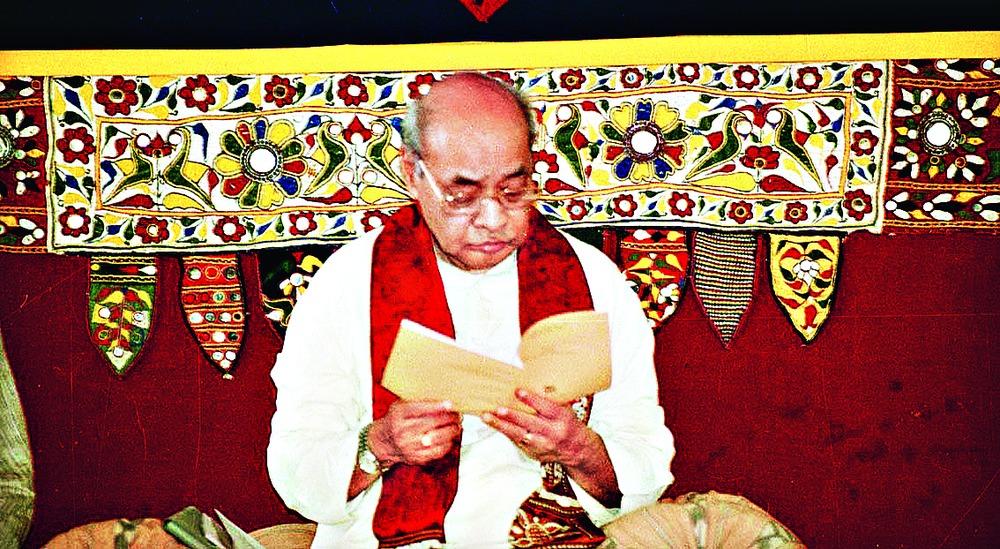

HALF LION: HOW P.V. NARASIMHA RAO TRANSFORMED INDIA By Vinay Sitapati, Viking, Rs 699

The curious title is from the Bhagavata Purana, which describes Narasimha as half-man, half-lion, and is an allusion to the former prime minister's ambiguous and complex character and his "dual disposition... at once principled, at once immoral". Written by an academic but in an accessible style with innumerable testimonies and references, the book seeks to portray P.V. Narasimha Rao as an excellent improviser, who knew his limitations and is underrated for his skill and bravery in implementing the first and most important wave of economic reforms in post-Independence India.

Rao was not in control of Parliament or his own party, but his prime-ministerial tenure lasted a full five-year term. He was a statist who partly liberated the private sector, and Manmohan Singh and M.S. Ahluwalia were other poachers turned gamekeepers. Rao was a member of legislative assembly, minister of state, chief minister, general secretary of the Congress, member of parliament, minister of external affairs, home affairs, defence and human resource development. In all these posts, he seems to have emerged unscathed, even from the anti-Sikh riots, Rajiv Gandhi's rejection of a uniform civil code, the ill-fated Rajiv intervention in Sri Lanka and the hasty exit of the chairman of Union Carbide, albeit without close allies but, which is perhaps more important, without sworn enemies. Vinay Sitapati charitably describes this as the quality of a team player and perfect courtier, whereas others might regard it as opportunism and ambition cloaked in, what Sonia Gandhi's claque accused Rao of even after the economic recovery, "procrastination, delay and the status quo".

Naturally, the apex of Rao's career was his tenure as prime minister - the first outsider in a monopoly controlled until then by the Gandhi-Nehru family - and the economic liberalization steps that were introduced. These reforms were undertaken by stealth, invoking Congress giants like Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi, and also Rajiv, with an eye to Sonia's concurrence. These measures in the teeth of opposition by the political Left, Congress traditionalists and the 'Bombay Club' of protectionist business circles, but supported by the reform-inclined Confederation of Indian Industry, involved a new Exim policy, industrial and telecom policies, reduced subsidies, eased foreign investment, liberalized foreign exchange, free pricing of public issues, private TV channels, private airlines, and joining the World Trade Organization. All these steps were taken with Prime Minister Rao remaining in the background and allowing others to absorb the inevitable criticism. But it remains to Rao's credit that he selected instruments from the political and civil services who were energetic and dedicated enough to carry these measures through.

The author states, "the demolition of Babri Masjid has become the principal taint on Narasimha Rao's legacy." Sitapati's chapter on this subject shows Rao as a Hamlet-like figure, torn between several courses of action but eventually finding it impossible to act. He wanted to protect all three: the mosque, Hindu sentiments and his government. He was prevented from intervention in Uttar Pradesh to foil the mosque's destruction due to the constraints of the Constitution on imposition of president's rule, and none of his close advisers gave him clear counsel. He was too overconfident in managing Hindu religious groups, although he failed to reach out to the Bajrang Dal and Shiv Sena.

In the Congress, the relationship between Rao and Sonia deteriorated from being correct and cordial to becoming one of distance and distaste. Sonia implied that Rao's premiership was contingent on his sensitive handling of the Bofors scandal and prompt investigation of Rajiv's murder, and with neither was she convinced that Rao was doing his best. Rao brought her ire on himself when, feeling strong enough, he stopped taking the time to brief her in 1993.

This book gives for the first time the steps taken by Rao towards testing a nuclear device, from which he eventually desisted under pressure from the Americans. The Prithvi missile was, however, deployed with the army despite similar pressure.

There are too few accounts of Rao's personal life. He was too private a person to reveal much of himself, although Sitapati gained access to his personal papers. From his early years, he was associated with Hindu god-men. He made his first trip overseas at the age of 53. The biography is unable to throw much light on his "barbed relationship" with his children, but alludes to his two long-standing romantic affairs. In his official capacity, he was chauffeur-driven for decades, and at one stage, he exclaims, "I had forgotten what traffic is like." I recall an occasion at the Amsterdam airport when Rao, then briefly out of office, was seemingly unaware that one had to pay for one's telephone calls.

This biography had to be written as a corrective to Rao's belittled reputation and is worth a dozen of the self-serving autobiographies that have recently appeared covering much of the same period. Thus Salman Khurshid is quoted as saying, Rao "is remembered for so much that went wrong but not for so much that went right". Was Rao a man of high principle? Sitapati veers towards a favourable conclusion, but how is one to explain Rao's failed bid for the presidency in 1987 and his dash to the capital after Rajiv's death, so as to be in the reckoning for the top job? The biographer may not be entirely convincing about the fact that Rao was not just another careerist politician, but he concludes that "the job of leading the world's largest democracy remains mired in contradiction." How true.