FRANCIS BACON IN YOUR BLOOD: A MEMOIR By Michael Peppiatt, Bloomsbury, Rs 599

What does it mean, or what does it feel like, to have someone "in your blood"? It is a metaphor that mixes kinship and contagion, suggesting an encounter that is inevitable. Somewhere between privilege and doom, it is closeness of a sort that breeds as much productive resistance as hindering intimacy. Michael Peppiatt was 21 and Francis Bacon 53 when they met in London in 1963. According to Philip Larkin, the English poet, it was the year "sexual intercourse began". He puts it in history "between the end of the Chatterley ban/ And the Beatles' first LP."

The intercourse that began between Peppiatt (straight and timid) and Bacon (gay and rampant) wasn't sexual - in the sense that there was no sex, which need not, of course, make things asexual - but it deeply and irreversibly changed the direction, nature and quality of the younger man's life and work. For Peppiatt, 1963 turned out to be exactly what Larkin had called his poem: the "Annus Mirabilis", in which life suddenly becomes a "brilliant breaking of the bank,/ A quite unlosable game." "Breaking of the bank" is surely a pun - a flood as well as a heist. Transgression was the name of this game, and Middle England, bored out of its wits since the end of the war and Empire, was desperate to play it again. Oscar Wilde had died long ago, and Auden had turned American.

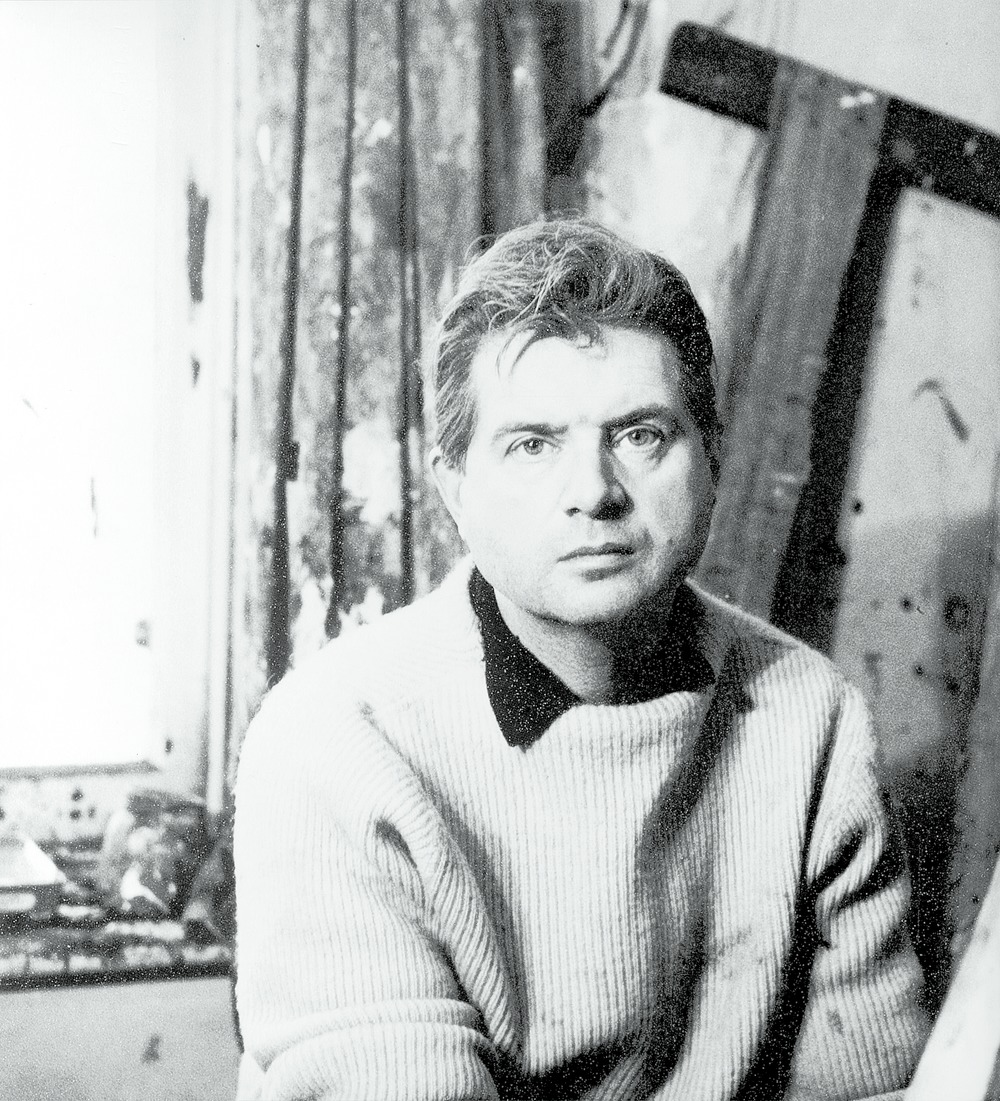

Inequality of age, class, intellect and achievement, together with the peculiar self-consciousness that such things take on in England, was built into the way Bacon, to shift the metaphor a little, got under Peppiatt's skin. More or less comparable to a summer's day, Peppiatt was then an Art History undergraduate in Cambridge trying to revive a dormant student magazine with an issue on modern art in Britain; his parents were unhappily married, middle-class Londoners, his father was bipolar, and his school had only been obscurely public. Bacon, on the other hand, had had his first big show at the Tate the year before. Already regarded as a genius painter, as much among the European avant garde as among the "lost souls of Soho", he was making and unmaking large sums of money, and was given to drifting from "bar to bar, person to person" driven by champagne, wit and the death wish, all of which had begun to come together as parts of a brilliantly self-curated personal mythology.

Repeatedly told that he couldn't bring out his issue of the magazine without having Bacon in it, Peppiatt gets to the artist at last for an interview, in a bar in Soho. He is surrounded by a threatening moat of queens in various stages of inebriation and decay, led by the photographer, John Deakin - the "Mona Lisa of Paddington" - from whose photographs of models Bacon had made some of his most famous paintings. Mysteriously for Peppiatt, Bacon pulls him into his inner circle in an instant, thrusting into his hands a glass of wine that could well have been the Grail: "'Here's to everything you want,' he says to me, anointing our newly formed group with a radiant smile. 'I can't wish you more than that, can I?' 'To everything you want,' the others repeat in unison, as if we have engaged in a secret rite."

Thus began a "complex, volatile relationship" that lasted through homosexual thick and heterosexual thin for three decades until Bacon's death. It was an amitié amoureuse that generated an invaluable archive of diaries and records, material as well as intangible, maintained by Peppiatt out of an immediate and overwhelming sense of vocation. Here was an extraordinary artist, and it was nothing but pure chance - if chance is ever pure - that had brought them together. So, he must "get it down", as Deakin had commanded him once. Peppiatt quickly trained himself to capture - first in his memory, and then in writing - the exhaustingly interminable, mesmerizingly repetitive, and brilliantly unflinching talk that came out of Bacon during their meetings, binges, sojourns and skirmishes over the years. He has produced a proper biography out of all this material, apart from a lavishly illustrated book on Bacon in the 1950s, the years before they met. But Francis Bacon in Your Blood is a less proper, and more troubling, complicated, flawed by overwriting, and therefore more valuable, book. Peppiatt writes himself into it with a candour that sometimes risks leaving the reader uneasy with, or even cringing at, the unabashed use - there is no other word - that the two men make of each other and of the inequalities that draw them closer and closer apart. So, in Peppiatt's life, 'growing up' and 'going up' become one and the same story of "doing the Bacon", symbolized by that steep flight of stairs leading up to the notorious chaos of the painter's studio. And this is how Bacon, with his "masochistic generosity", wanted it written, too, when the writer first suggested such a book to him: "the more indiscreet it is the better... if you're going to tell the story, only the whole story is worth telling." This was, of course, before making it, in his usual contradictory way, as difficult as possible for Peppiatt to get the book published during Bacon's lifetime.

Just as well, perhaps, for the passing of time - Bacon died in 1992 - gives to Peppiatt's book an aura of authentic loss and longing that comes close to the spirit of Bacon's fellow-asthmatic, Marcel Proust, whose Time Regained the painter would read over and over again, calling it "the last great tragedy that's been written". While I was reading Peppiatt's book, I also happened to be watching, by sheer coincidence, Raúl Ruiz's exquisite film of this last volume of Proust's novel, and the incessant, slowly circular and slightly sickening movement of Ruiz's camera, catching the phantasmagoric disorientation of Proust's deathbed memories, together with the relentless morbidity and abjection of the Baron de Charlus (Proust's great vision of perversion, and Bacon's favourite character), merged in my mind with the ebb and flow of time and alcohol-fuelled talk recorded by Peppiatt, at the heart of which would always be Bacon's vision of "nothing, just nada, nada": "it's not just the circularity of places and the deadening recurrence of bottle after bottle which in themselves gradually swallow up all notion of time but the circularity imposed by Francis himself as he repeats what he just said, again and again like a mantra, until you feel imprisoned in a tightening circle of nihilism and finality." Reading this claustrophobic book, full of its own anxieties and panic, is a very different experience from reading that other, perhaps more self-assured and enduring, book of interviews with Bacon, The Brutality of Fact, by David Sylvester. He was Peppiatt's chief rival among the "vestal virgins tending to the sacred flame", and therefore the subject of some wonderfully unkind anecdotes in the memoirs.

The bravura writing that forms the core of Peppiatt's book, and captures, almost like great cinema, the grandeur, tragedy and, above all, the chilling classicism of what Bacon used to call his "gilded gutter life" of art, love and drink, comes in a chapter called "A Death Foretold" in the middle of the book. Bacon's lovers had mastered the art of timing their suicides with the openings of his great shows, and in this chapter, Peppiatt narrates the experience of being with Bacon in Paris during his exhibition at the Grand Palais in April 1971, a major show with more than a hundred paintings, after the opening of which, at the grandest of banquets hosted by Bacon, the news arrived of his lover, George Dyer, a failed burglar, having killed himself in the hotel room where he and Bacon had been staying. There is a matchless conversation between Bacon and Peppiatt in front of Monet's Waterlilies at the beginning of the chapter. But its high point comes during the banquet after the news of Dyer's suicide, with Bacon deciding to go ahead with the dinner, and Isabel Rawsthorne, his friend and subject, getting up to make a speech: "Isabel's high, insistent voice rises like a rant, drowning out all whispered commentary in a stream of increasingly incomprehensible phrases that sound as if she was speaking in tongues, inducing an awed silence in every corner of the room. She is addressing Francis opposite her, as if he had asked her a question and she can no longer contain the truth now or for the future as it wells uncontrollably up in her. And everybody sits there, stunned, as she appears to be saying that this is what she had seen coming, fatally, and now that it was there it was final, and this was the price that had to be paid. And Francis sits there immobile, his head bowed." Trained in "living art" by the great painter himself, Peppiatt also describes how, during Isabel's speech, the waiters had been darting around, noiselessly plying the guests with the Rully Clos Saint-Jacques and the Côte de Brouilly Château Thivin, both 1970, "as frequently and plentifully as possible".