Thanks to a humongous oversight on the part of the government, India’s unorganized labour has suddenly become a vivid, long-running story. Photographers walk with families undertaking unimaginable journeys. Reporters tail them in SUVs. Their faces and daily tragedies have dominated newspaper headlines and television news for two months running, something nobody would have ever thought possible. Since when did hyperventilating news channels focus on the travails of the poor?

But how did a segment of the population numbering at least 80 million, going by the government’s provisioning for them, become so invisible that the State did not plan for them while preparing for a nationwide lockdown? As Atul Sood, a professor at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, put in one of the many Zoom discussions taking place, “In the imagining of the so-called lockdown... there was no imagining of labour.” But the question is why?

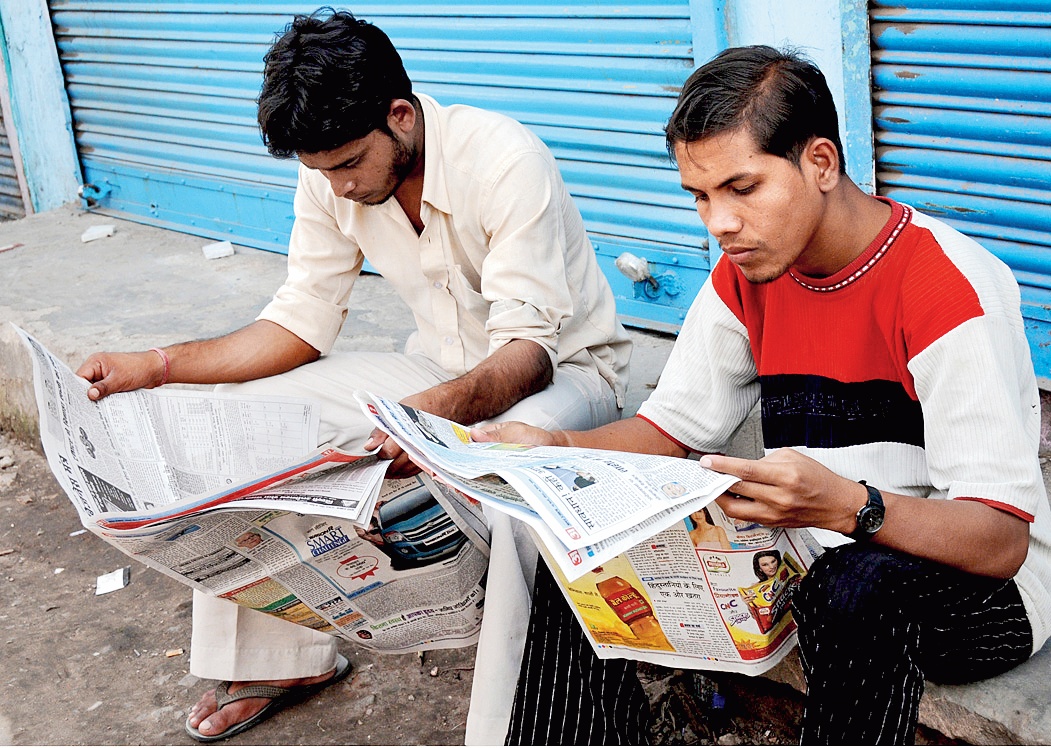

The media have been partly responsible for their invisibility, until they chose to make them visible. Unorganized labour, with no formal representation, was not on their radar. Tracking labour has not been a news beat for a few decades. Covering the ministry of labour and employment and the organized labour via trade unions was something that lost relevance with the advent of liberalization in the 1990s. And even when it was a beat, it did not cover unorganized labour whose numbers had begun to grow as smaller unions were disbanded and contractualization set in.

The trade unions themselves have done little to project the travails, or indeed the existence, of migrant workers or other categories of informal labour. The problems of vulnerable unorganized labour are more likely to be responded to by civil society organizations. Last week the major unions held countrywide demonstrations, billed to be in solidarity with these circular migrants. But there was no mention of the migrants in their demands, which focused on the withdrawal of changes in labour laws, and opposed privatization of public sector enterprises. The red flag protests got no coverage at all except on Left-liberal websites.

A third reason is the lack of data (https://www.livemint.com/news/india/why-india-s-migrants-deserve-a-better-deal-11589818749274.html) on circular migration. The government has no identification or registration of informal, interstate labour coming into cities, either on their own or through contractors. So it was just not aware of the scale of their presence.

And a fourth reason linked to the third is spelt out in an analysis (https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/india-lockdown-inter-state-migrant-workmen-act-6400710/) of why a key piece of legislation governing interstate migrants in India — the Inter-State Migrant Workmen Act of 1979 — fails to ensure their registration and protection and, thereby, their formalization. It was enacted to prevent the exploitation of interstate migrant workmen by contractors and to ensure fair and decent conditions of employment. If it had been implemented properly, state governments would have had the details of interstate migrant workmen coming through contractors within their states. But the law has so many onerous compliance requirements that it proved impossible to implement, making it too costly to hire interstate migrants formally.

The media’s own role in invisibilizing such labour has gone through different stages. In his 2018 memoir, The Post-Truth Media’s Survival Sutra, the veteran political reporter, P. Raman, describes the “universal, permanent list of pariahs” in the newsrooms of the leading English dailies of the 1980s: “trade unions, Left parties, the Bahujan Samaj Party and rural issues — in that order”. He writes that if there was an all-India bandh, the chief sub on the night edition was expected to know better than to put it on Page 1. Strikes were to be reported from the lens of the disruptions they caused, if they were reported at all. Newspaper proprietors were allergic to trade unions.

Then came the 1990s and the decade of liberalization and upward mobility for both India’s middle class and the press. There was little sympathy for organized labour, which was synonymous with trade unions and strikes. Post liberalization the middle class and upper middle class also had little interest in reading about poverty, the media catered to upwardly mobile consumerist readers, and the poor became invisible, except in calamities. Readers were not presumed to be interested in the travails of the working class, which then slipped below the radar and stayed there. The invisibility persisted through the first decade of the next century even as smaller unions disappeared with growing contractualization, and the informalization of labour grew.

The big irony in all of this was that journalists in the mainstream publications persisted in wanting labour protection for themselves via the Working Journalists Act (which mandated periodic wage board announcements for working journalists), even as they ignored the unorganized sector. In the current overhaul of labour laws being undertaken however, the wage boards have been scrapped.

The other reason for the invisibility of migrants who build cities and keep the wheels of micro, small and medium enterprises running is the attitude the Dutch sociologist, Jan Bremen, cited in a Zoom webinar on labour and the pandemic (https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?v=302921200702336&ref=watch_permalink): “Labour should behave as a commodity, not have citizen expectations.” Cities don’t look at migrant workers as human beings, he added. They are anonymous, and not meant to become citizens.

But when millions of them poured out of the same cities and hit the road, they became a phenomenon impossible to ignore, for the media and for the rest of the entitled citizenry of Delhi, Mumbai, Ahmedabad and elsewhere. An inured middle class and upper class suddenly discovered their existence, and were at least temporarily shaken.

The absence of regular media coverage of the working classes perpetuates both invisibility and inequality. Sanitation workers throughout the country enter drains every day without equipment despite two laws rendering manual scavenging illegal. They make news only when they die. Bonded labour still thrives in pockets of the country. And mandated minimum wages remain a myth despite legislation. All of these issues merit precious little focus even as the government has embarked on a major reorganization of labour laws into four codes, including one on social security. The invisibility helps to explain what the civil society activist, Harsh Mander, describes as the privileged Indian’s ability to be comfortable with some of the most unconscionable inequalities in the planet.

The recent watering down of labour laws in some states triggered by the collapse in economic activity has served to revive an editorial engagement with the issues of wages, labour rights, and access to social security. The dilution of protections, particularly the lengthening of the working day in at least 10 states, has outraged many. However, the fact is that a 12-hour working day has long been the norm for informal workers without either journalists or citizens losing sleep over it.

Labour law reform is not the sexiest of subjects. But the events of the last two months have made humanizing it that much easier. Will more journalists now wake up to the challenge of turning sweat labour into citizens for their readers and viewers?

The author is a media commentator and was the founder-editor of TheHoot.org