BECOMING A MOUNTAIN: HIMALAYAN JOURNEYS IN SEARCH OF THE SACRED AND THE SUBLIME By Stephen Alter, Aleph, Rs 495

Life is idyllic for those lucky enough to have their homes on the Landour ridge above Mussoorie. The hill station that Frederick Young, a British soldier, founded in the 1820s is now overcrowded and hideously commercialized. But Landour, with its splendid isolation and magnificent views of the Himalayan peaks, still retains much of its old charm.

Stephen Alter, who was born in Mussoorie and whose family has lived there for almost a century since his grandparents first spent a summer in the hill station in 1916, has always known those mountains as his 'birthright'. So when armed intruders invaded their Landour home a few years ago and inflicted grievous wounds on him and his wife, Ameeta, their world of Himalayan bliss came tumbling down. They took weeks to recover from the physical injuries. But, how to recover from the trauma and handle the sense of loss tormented Alter even more.

There was only one way he could survive the crisis, he realized, and that was by going back to the mountains. This book is an account of the journeys he undertakes in order to recover from the near-fatal assault on his body and mind. And the three treks he embarks on are chosen carefully, for the three mountains - Nanda Devi, Bandarpunch and Mount Kailash in Tibet - are not only among the most difficult destinations in these heights but also offer the best in religious mythology and Himalayan folklore. He journeys to these mountains, not so much to climb them as to try and know once again what mountains mean. The result is a rich narrative in which myth and memory mix with vivid descriptions of the natural world.

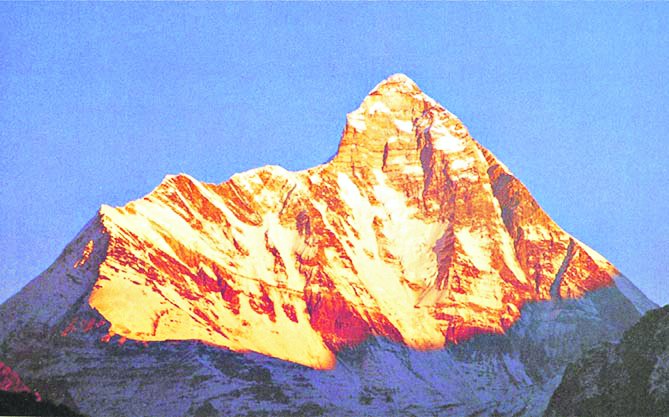

Nanda Devi is not only the second highest mountain in India but is also arguably the most beautiful of the Himalayan peaks. Only Ama Dablam, often called the Matterhorn of the Himalayas, equals Nanda Devi's beauty. One of the most difficult to climb, Nanda Devi is also the most sacred of the mountains in all of Garhwal and Kumaon. The biggest religious festivals and pilgrimages in the Indian Himalayas centre around the myths about this mountain goddess. As he crosses the passes, the valleys and the ridges on his way toward the Nanda Devi sanctuary, Alter narrates the sacred traditions associated with the mountain. He also has memories of mountaineers of yore who made it to its top and others who died on their way up or down.

Many of these stories have been told and retold. Early heroes such as Eric Shipton, Bill Tilman and Noel Odell are remembered as much as latter-day pathfinders like Dorjee Lhatoo. The most dramatic - and tragic - story of an ascent of Nanda Devi - of Willi Unsoeld's burial of his daughter on the mountain - is touchingly retold. The American girl had been named Nanda Devi by her father, whose favourite mountain it had always been. Near the base camp of the Nanda Devi sanctuary, Indian climbers later erected a memorial to the girl. The inscription on it was taken from her diary: "I stand upon a wind-swept ridge at night with the stars bright above and I am no longer alone but I waver and merge with all the shadows that surround me. I am a part of the whole and am content." Alter does not forget, however, to tell the other well-known story of the 'desecration' of the mountain when American and Indian intelligence agencies together planted a nuclear-powered sensor on the mountain's summit to keep a watch on China's atomic weapons tests in Tibet.

In Hindu mythology, Nanda Devi is the mountain bride of Lord Shiva, who sits in meditation on Mount Kailash. "If I were to ride on the wings of a Himalayan griffon across the mountains, soaring from Bandarpunch to Nanda Devi, then follow a straight line towards Tibet", Alter would often tell himself, "the trajectory of our flight would take me directly to Kailash, no more than 300 kilometres away." So, soon after the trek to the base of Nanda Devi, off he sets on a journey to Kailash and Manasarovar in Tibet.

Once again, he takes us through a maze of ancient faiths and modern facts, citing Hindu and Buddhist religious texts as well as modern-day tales of expeditions and exploits. The journey to Kailash and Manasarovar, though, is different from the one to Nanda Devi. This time Alter is part of a group of Indian pilgrims driven for two weeks in a convoy of several Land Cruisers. Reflections on religious rituals and practices alternate with wry observations on the eccentricities of some of the Indian pilgrims, the absurd ways of the Chinese police or the co-existence of faith and filth in sacred places. And, as he finally has his first view of Kailash, he has mixed emotions. His has not been a pilgrim's progress, yet "my vision blurs with tears and my throat constricts, not from altitude, but from a sense of having arrived." Kailash, after all, is "nothing but an enormous mass of rock covered in snow and ice".

At Kailash, the success of the journey brings no religious joy to Alter. On the expedition to Bandarpunch, the failure of the mission makes no difference to the sense of fulfilment. The personal journeys that the book narrates are ultimately less about the mountains than about the mind that defines them. That is not to say, though, that the natural world, with its beauty, terror and mystery, is not important. But the more important thing, Alter tells us, is "to become a mountain". Obviously, an idea like that sounds a bit trite. But Alter's evocative language and the range of his references make us understand what mountains can mean.

The brief chapter, "Healing Light", is an excellent example of what the author wants us to know about the quintessential nature of 'becoming' a mountain. He talks about the very special quality of light in the mountains at different times of day and night. But when he says, "Certain light, found only in the mountains, travels with us as we ascend", we know he is talking of an illuminated mental landscape.