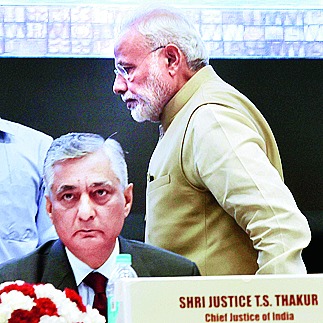

WORK TOGETHER

The Centre has returned the list of 77 names that was sent to it by the Supreme Court collegium. The majority of names were rejected. The collegium has now rejected the Centre's plea for "reconsideration". The action will only increase the acrimony between the apex court and the government.

More than a year ago, a Constitution bench of the apex court struck down the National Judicial Appointments Commission Act and the Constitution (Ninety-Ninth Amendment) Act. The laws, experts claim, violated the basic structure of the Constitution. To avoid embarrassment, the Centre attempted a cover-up. An old adage goes like this: 'the last resort for a losing attorney is to change the narrative of the story'. The government, too, shifted the narrative of the debate from 'the role of executive in appointing judges' to 'the authority of the Supreme Court to strike down laws passed by Parliament'. Arun Jaitley's "tyranny of the unelected" comment (it is supposed to have been misinterpreted) is one example of how the government tried to change the course of the debate.

The apex court and the government are still working on the memorandum of procedure to establish the norms of judicial appointment. They must ensure that the new law does not violate the spirit of the Constitution. Whether the government ought to have a role in the appointment of judges needs to be debated. Article 50 talks of the separation of powers, stating "The State shall take steps to separate the judiciary from the executive..." "State" includes Parliament, the Union government, state governments and the Vidhan Sabhas.

Regarding the appointment of judges, the apex court observed in the Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association versus Union of India (1993) that the government must voluntarily "reduce its role to one which is purely formal or ceremonial, ensuring that the decisive factor is the wish and will of the judicial family." Article 50 is a part of the directive principles of state policy and cannot be enforceable in a court of law. The MoP must be consistent with democratic values.

Conflict of interest also makes it difficult for the government to have a role in the appointment of judges. The principles of natural justice imply that litigants should have no role to play in selecting the judge who would settle the dispute.

The nullifying of the NJAC also raised serious doubts about the authority of the Supreme Court. The NJAC Act was passed unanimously by both Houses. Article 141 of the Constitution says that the laws passed by the Supreme Court are binding on all authority and, therefore, are "the law of the land". The top court not only enjoys the right to 'declare' and 'interpret' laws, but also test their validity and implementation.

This is not to say that the collegium system is transparent. Justice J. Chelameswar, in his lone dissenting judgment while upholding the NJAC Act, said that the collegium system is "absolutely opaque and inaccessible both to public and history, barring occasional leaks." Discussions in the collegium are never recorded and minutes are not maintained. This has allegedly led to favouritism and nepotism. When the NJAC Act was struck down, the collegium was resurrected. Since October 2015, the collegium system of appointment is the law.

It could seem that the government's decision to draft the MoP was an unwise move. It should have redrafted the act, passed it in Parliament and allowed its validity to be tested in the court again. Litigants are suffering as a result of this bruising battle between the executive and the judiciary. Vacancy in the higher courts stands at above 40 per cent. Both the judiciary and the executive must resolve the crisis at the earliest.