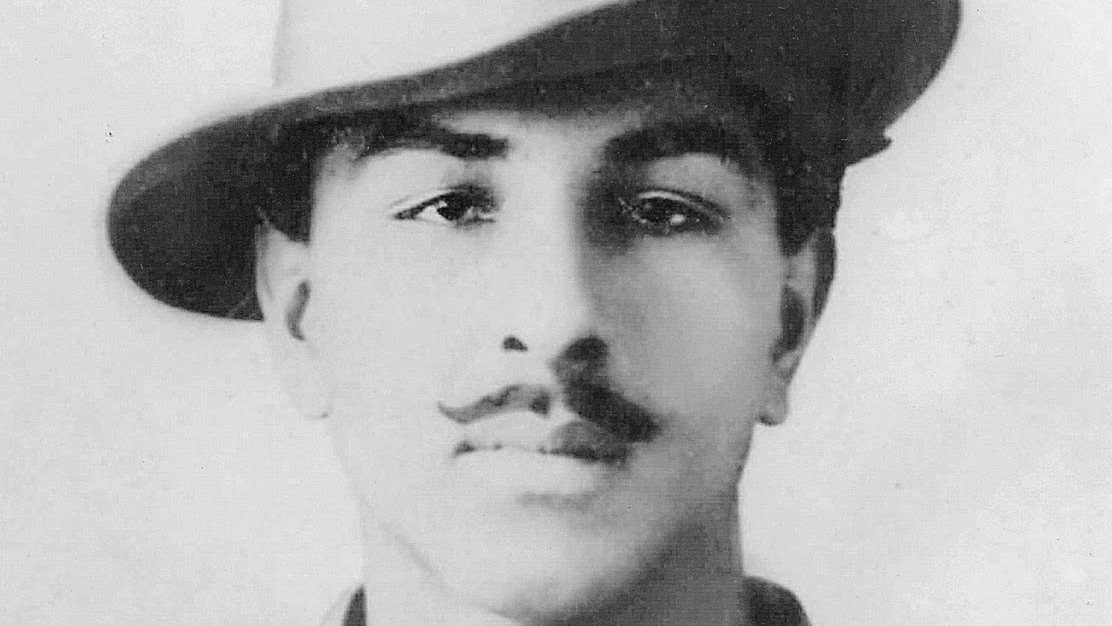

Today is the 90th death anniversary of Bhagat Singh. He was one of the tallest revolutionary freedom fighters, sacrificing his life at the age of 23. Many other revolutionaries died even younger. But Bhagat Singh was different. He was not only a martyr, but also a political and social visionary. In the introduction to his book, Inquilab, the historian, S. Irfan Habib, explains why this is so: “We do great injustice to his memory when we extol him only as a martyr. Bhagat Singh left behind a corpus of political writings underlining his vision for an independent India.”

Bhagat Singh lived a very short life but with a privilege that very few had. He was born into a family of nationalists. His father’s younger brother, Ajit Singh — he spent most of his life in exile — was a crusader against imperialism; another uncle, Swaran Singh, underwent many years in prison, defying the British; his father, Kishan Singh, was a Congressman who participated in the Non-cooperation and Civil Disobedience movements and swore by the Mahatma’s ideology and the objectives of the Indian National Congress. Given this political background, Bhagat Singh matured early as a great patriot and revolutionary thinker. He spent a great deal of time reading and writing. When he was only 17, he wrote an article on ‘Universal Brotherhood’ in which he says: “Vishvbandhuta! For me the greatest meaning of the word is equality and nothing else…”

In 1926, at the age of 19, Bhagat Singh founded the Naujawan Bharat Sabha, an organization of a secret group of young revolutionaries. The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh had been founded in 1925 and the Muslim League two decades earlier. Despite the positive impact of the Khilafat and the Non-cooperation movements on Hindu-Muslim relations, polarization was on the rise, once again. To his credit, the young revolutionary took a completely secular approach. The members of the Sabha were asked to sign a pledge that they will “place the interest of their country above that of their community”. A part of its manifesto read: “Religious superstitions and bigotry are a great hindrance in our progress… and we must do away with them. The thing that cannot bear free thought must perish.”

Bhagat Singh wrote regularly for Kirti, a journal founded by the communist leader, Sohan Singh Josh, who influenced his move away from anarchism towards socialism, a creed which Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose were propagating from the platforms of the Indian National Congress. Their charisma and popularity among the youth influenced Bhagat Singh and the other revolutionaries.

The year, 1928, was eventful in the history of the Independence movement. It was the year of the Simon Commission, the Bardoli Satyagraha and the presentation of the Nehru Report prepared by Motilal Nehru, who presided over the 43rd session of the Congress in Calcutta. In a column written for Kirti in July 1928, Bhagat Singh talks of Nehru and Bose in glowing terms: “Many new leaders with modern thoughts are emerging... The most important young leaders in the present scenario are Bengal’s Subhas Chandra Bose and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. These two leaders are making their presence felt and are participating in the movements of the youth in a big way. Both are wise and true patriots. Still there are considerable differences between the views of these two leaders. One is called the worshipper of ancient Indian culture while the other is called a staunch disciple of the West.” He goes on to explain the differences and exhorts the youth to understand the true meaning of Inquilab: “Subhas favours complete independence because he says that the English are from the West and we are from the East. Nehru says that we have to change the entire social system by establishing our government. For that it is important to obtain complete independence, Subhas sympathises with the workers and he wants to improve their situation. Nehru wants to change the system itself by a revolution. Subhas is sentimental, for the heart... Nehru is a revolutionary who is giving a lot to the heart as well as the head... They... should aim at Swaraj for the masses based on Socialism...”

Even though Bhagat Singh went to the gallows avenging the death of Lala Lajpat Rai following a brutal lathi charge, a few months earlier, he had castigated the ‘Lion of Punjab’ for his association with the Hindu Mahasabha. Lajpat Rai responded by calling Bhagat Singh a ‘Russian agent’. Despite this exchange, Bhagat Singh could not tolerate Punjab’s tallest national leader being beaten at the hands of an Englishman.

Bhagat Singh’s most popular work, Why I am an Atheist, was written in October 1930 while he was in jail. In this long article, Bhagat Singh raises many questions: “I ask why your omnipotent God does not stop every person when he is committing any sin or offense?… Why did he not kill war overlords or kill the fury of war in them and thus avoid the catastrophe hurled down on the head of humanity by the Great War? Why does he not produce a sentiment in the minds of the British people to liberate India? Why does he not infuse altruistic enthusiasm in the hearts of all capitalists to forgo their rights of personal possessions... and redeem the whole society from the bondage of Capitalism?”

Bhagat Singh had a message for the press that seems relevant today: “The real duty of the newspapers is to… cleanse the minds of the people, to save them from… sectarian divisiveness and to eradicate communal feelings to promote the idea of common nationalism.”

How should we remember Bhagat Singh today? The best homage citizens can pay is by fighting fearlessly the forces that propagate communalism, hatred, superstition and economic disparity.