Poona , 1793. Two British surgeons, James Findlay and Thomas Cruso, were baffled when confronted by an Indian man desperate for a nose job. The man, a bullock-cart driver named Cowasjee, who worked for the British army, had excellent grounds for his desperation: he had been captured by Tipu Sultan, who had cut off his nose and released him as a warning to traitors. The surgeons did not know how to reconstruct a nose. To their amazement, they were to discover that there was someone who did. The 'nose reconstruction specialist' - brought in from 400 miles away - turned out to be an Indian potter. The British surgeons witnessed the entire surgery and were so impressed that they published an account of the operation in the Madras Gazette , with "before" and "after" pictures of Cowasjee.

The operation created a stir in British medical circles. The soundness of the reconstructed nose, which the potter-surgeon had constructed by using a flap of skin from the patient's forehead, was verified by a number of experts. Curiously, the potter had claimed that the procedure was based on hereditary knowledge. This raised more questions, particularly about the identity of the original inventor of the technique of Indian rhinoplasty.

The Karakoram Pass, 1888-90. The Russians were vying with the British for control over Central Asia. Andrew Dalgleish, a Scottish merchant and possibly a British spy, was making one of his regular trading trips, carrying goods from Leh to Central Asia by way of the Karakoram. Somewhere in the snowy mountains, he was joined by a Pathan trader named Dad Mahomed, who murdered him once the small band of traders had set up camp after crossing the Karakoram pass. Mahomed then fled. The British, suspecting a possible Russian conspiracy, assigned one of their intelligence experts, Hamilton Bower, to find Mahomed. Bower began trawling Central Asia in search of the murderer. In the course of his travels, he spent some time in a village called Kuchar at the foot of the Tian Shan mountains. There, he met a local of Turkish origin who had lived in India. The man showed him a birch bark manuscript written in a script that Bower could not decipher. Recognizing the value of the manuscript, Bower bought it, and presented it to the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal after his successful return from the mission. Once the manuscript was deciphered, the Bower Manuscript, as it came to be known, eclipsed Bower's mission.

The manuscript contained references to an ancient Indian surgical and medical expert by the name of Sushruta. Who was this mystery medical man? Why was he famous enough to be discussed in a manuscript traced to a remote Buddhist monastery? Happily, the Indologists already had a crucial missing piece - a Sanskrit manuscript called the Sushruta-Samhita attributed to Sushruta - in their possession. This manuscript contained an astounding array of surgical techniques, and was later translated into Arabic.

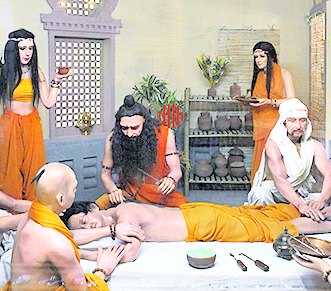

A reading of Sushruta's book reveals diagrams and descriptions of more than a 100 different kinds of surgical instrument, and descriptions of complicated cataract surgeries. The book also reveals Sushruta's ingenuity in acquiring knowledge of anatomy. Sushruta devised a method for decomposing a corpse in water and then scraping the tissues off the body using a special brush made of bamboo and grass roots. This would give would-be surgeons an idea of organs and bones. Sushruta also used the bodies of animals sacrificed in rituals to teach his students anatomy and dissection skills.

Most interestingly, the book contains techniques for reconstructing missing or deformed earlobes and for nose reconstruction. Similar techniques were used by the potter-surgeon in Poona. While Sushruta's techniques became known in the Arab and Persian world, it is a bit of a mystery as to why plastic surgery operations gradually became confined to a few members of an obscure potter caste. We may never know the answer.

For some unknown reason, surgeons all over the world experienced a dramatic decline in their status; witness the Roman Church's strict prohibitions on dissecting corpses and the relegation of surgical operations to barbers in the West. Surgery was illegal in east Asian countries like Korea and only gained acceptance with the spread of Western medicine in the late 19th and the early 20th centuries. It is comforting that Sushruta got the chance to push his ideas through and Indians in search of nose jobs reaped the benefit.