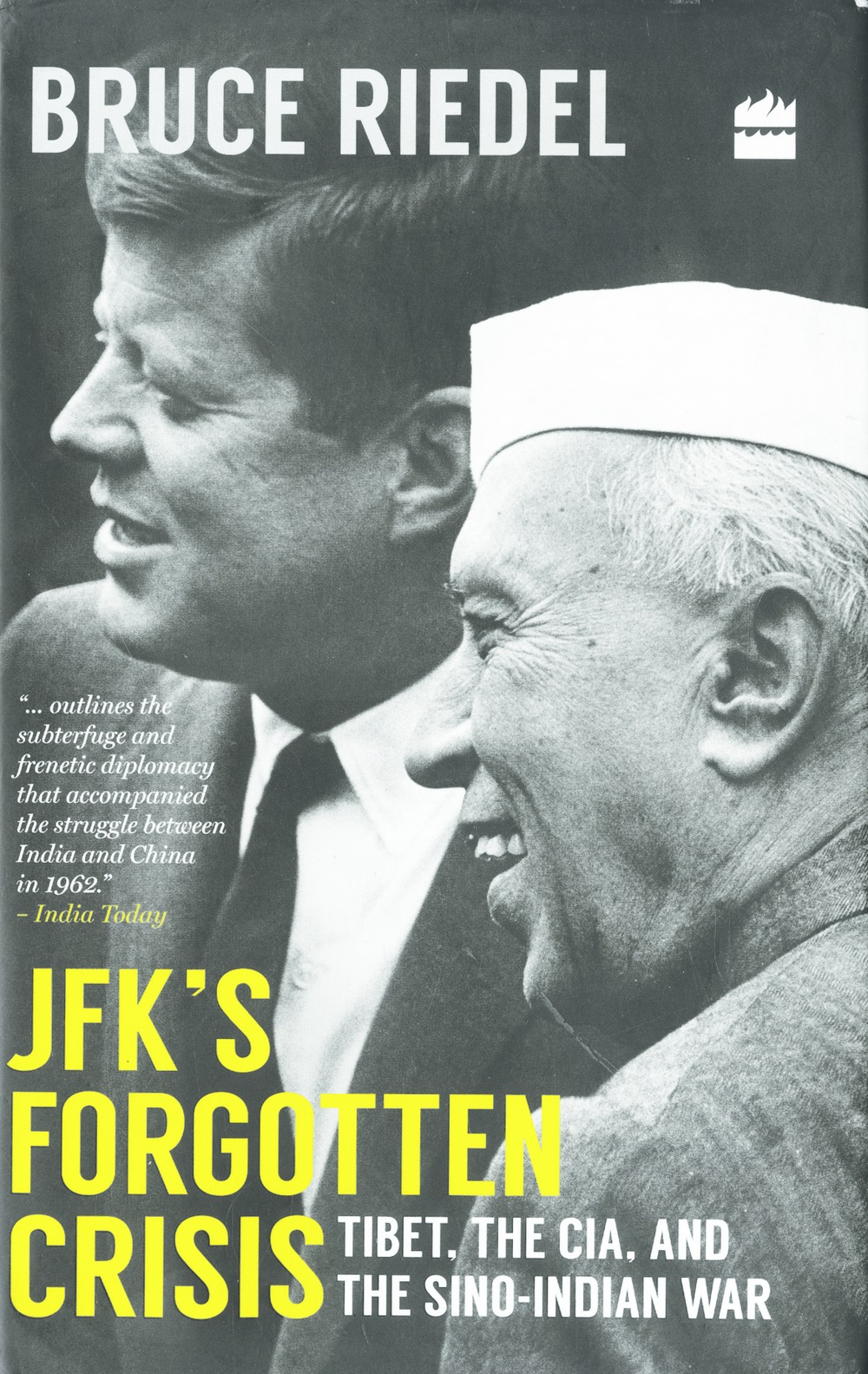

JFK'S FORGOTTEN CRISIS: TIBET, THE CIA, AND THE SINO-INDIAN WAR By Bruce Riedel,

HarperCollins, Rs 699

In November 1962, the Chinese People's Liberation Army, the world's largest military force, stormed through Arunachal Pradesh. India's Fourth Division, whose soldiers carried WWI-era rifles, disintegrated. Little stood between the PLA and Calcutta. Meanwhile, Field Marshal Ayub Khan of Pakistan contemplated invading Kashmir. South Asia's future hung in the balance.

In his clear and concise new book, Bruce Riedel demonstrates that the policy of the United States of America had a decisive effect at every stage of the war. While President John F. Kennedy's support of India ultimately saved it from catastrophe, his Central Intelligence Agency inadvertently helped cause the crisis. A former CIA analyst himself, Riedel is inclined to give JFK too much credit for his enlightened stance on India, and the CIA too little blame for its ruinous covert operations. His book is nonetheless an excellent introduction to a war that looms in the background of violence and militarism in South Asia today.

Before the fighting began, a strong Indo-American alliance seemed unlikely. Cold War strategizing dictated American foreign affairs in the 1950s, and it was Pakistan that signed two regional US security treaties, making itself America's "most allied ally," while India assumed leadership of the non-aligned movement. The two most important US operations in the area - the flight of U-2 spy planes over Russia and China and the dispatch of Tibetan rebels - were carried out from Pakistan. For hawkish American officials like Vice President Richard Nixon, Indian non-alignment was tantamount to collusion with the Communist devil.

As a young senator, Kennedy argued for a different approach. In a 1959 speech, he said India espoused "human dignity and individual freedom" against "Red China which represents ruthless denial of human rights". China, Kennedy went on, was developing at three times the rate of India thanks to Soviet economic aid. He proposed that the US invest $1 billion a year in India so that the democracy could keep pace.

Kennedy's views were inspired by John Kenneth Galbraith, a professor of economics at Harvard who was fascinated by India, having travelled across the country and discussed its economy with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in 1956. After the trip Galbraith told his wife, "When the Democrats get back in power, I think I will get myself made ambassador to India", which is exactly what happened when JFK took office in 1961. Riedel relishes such anecdotes about the swaggering intellectual. At a welcoming ceremony in India, Galbraith wore a black silk top hat that made the lanky man appear over seven feet tall. He demanded a direct line to the president, insistent that using the State Department was like "trying to fornicate through a mattress".

Galbraith was generally sceptical about the usefulness of CIA covert operations, and he opposed supporting the Tibetan resistance against China. He tried and failed to convince JFK that the US was "recklessly provoking the Chinese while having little chance of thwarting their takeover of Tibet," writes Riedel. Concern about the unintended consequences of intervention was justified. While Nehru's misguided refusal to compromise on the Sino-Indian border has often been blamed for provoking the initial Chinese offensive, Riedel shows that Chairman Mao Zedong had long planned an attack on India in retaliation for its supposed aid to Tibetan rebels. Nehru did give the Dalai Lama asylum, but it was Pakistan, not India, that enabled US-Tibetan strikes.

Foolhardy American support of Tibet was thus an indirect cause of the Sino-Indian War. The US was much more helpful to India during the war itself. Kennedy, using American leverage, restrained Ayub Khan from attacking India. Mao also chose not to press his advantage: after gaining decisive control of Aksai Chin, the PLA withdrew from Arunachal Pradesh and Mao declared that he accepted the status quo. Riedel argues persuasively that Mao must have been influenced by the airlifts of supplies to the Indian army organized by Kennedy and Galbraith, as well as the memory of the brutal war with American forces in Korea.

Riedel does not make the indictment of the CIA that his account seems to call for. He writes that "the Tibet operation never had any real chance of achieving its aims", but suggests that similar missions have been wiser and more successful. Bafflingly, he refers to the support for the mujahideen in Afghanistan as a "complete victory" and to the overthrow of Mohammad Mosaddegh in Iran as a "big success" without ever mentioning the repercussions. Riedel's book lacks an example of a covert CIA operation that did not end in disaster.

Riedel concludes that the war "created the balance of power, the alliance structure, and the arms race that still prevail today in Asia." Its effects were certainly far reaching. India soon started its nuclear weapons program, which even decades later Atal Bihari Vajpayee would attribute to the need to deter China. After the 1962 war Pakistan, newly distrustful of the US, began an alliance with China, causing the first of many US sanctions on Pakistan.

But Riedel overstates the import of 1962. The budding Indo-American entente, for example, soon collapsed. Riedel cites a poll that shows Indian approval of the US shooting up 55 points by the end of the year. Within a decade, however, Nixon would support Pakistan's genocidal slaughter of Bengalis in its civil war. The approval rating of the US went back down by 40 points, and India signed a treaty with the Soviet Union; relations between India and America wouldn't fully recover until the 21st century. JFK's time in office was fateful in many ways, but his untimely death was also a lost opportunity.