|

|

The arrest of the sankaracharya of the Kancheepuram math is more than a flash-point for the sangh parivar in its search for a new symbol of substance in the wake of its electoral routs in recent months. It also marks a significant change of tack by the Tamil Nadu chief minister, J. Jayalalithaa, who has encashed the older traditions of militant opposition to Brahmanical orthodoxy by proceeding with the incarceration of the Kanchi seer. In doing so, she seeks to re-capture a political space more commonly associated with other, more radical Dravidian outfits and also distance herself from the saffron outfits with which she has had a pre-electoral accord earlier this year.

The wheel has turned, and turned with a vengeance, for the head of the Kanchi math. In fact, it was the period of All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam rule, especially the early Eighties, when Jayendra Saraswati found political leaders much more receptive to his message than in the past. The chief minister herself has, on many occasions, called on the seer and been in close contact with him. Yet, many tend to underestimate her capacity to re-invent herself when the need arises. Her mentor, M.G. Ramachandran, had close personal ties with V. Prabhakaran of the the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, but she did not hesitate to go after them in the wake of the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi. Similarly, when Tamil Brahmins protested against reservation policies, she offered a 10 per cent quota, knowing well that it would be rejected.

She embodies the paradox of being a Brahmin heading a political party that recognizes E.V. Ramaswamy Naicker, the most influential radical social reformer of 20th-century Tamil Nadu. In the past, and most so in her recent spell in power since 2001, the chief minister has played on both religiosity and her affinities with Hindutva. The two are distinct. Her scheme for feeding the poor at temples won approval of the sangh parivar, but she is careful to turn up at dargahs and mazhars at appropriate occasions. But it was her presence at the investiture of Narendra Modi and her comments on Godhra that seemed to indicate a creeping saffronization of the polity. Even prior to that, Tamil Nadu enacted a bill against religious conversion that won encomia from the saffron fraternity and paved the way for re-negotiating an electoral alliance.

The May 2004 general elections saw such sanguine hopes fall flat, and there has been a change of tack ever since. With the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam and smaller parties lining up with the Congress, Jayalalithaa stood in danger of being politically isolated. The killing of Veerappan, a dacoit with a long record of evading the police forces of two states, was the first good news in a long time.

If anything, the rallies and demonstrations outside the state have seen the Bharatiya Janata Party play into the chief minister?s hands. In one fell swoop, she has transcended the memory of herself as a person who first allied with the BJP in Tamil Nadu in the 1998 election. It is also significant that this opens up lines of communication with the leaders of lower-caste outfits in north India. These may prove critical if Jayalalithaa ever embarks on her pet project of linking up with non-Congress, non-BJP parties.

Within the state, her actions won grudging support of her arch-rival, M. Karunanidhi. The rationalist DMK even clashed with pro-Rashtriya-Swayamsevak-Sangh volunteers outside the courts. But taking on the head of the Kanchi math is another matter altogether. Although the Brahmins make up only a minuscule three per cent of the population of the state, the early 20th century movements set the tone for much of popular political discourse. The last two decades saw the slow rise of Hindutva in public and political fora, but it still does not have the kind of clout it has in neighbouring states like Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh.

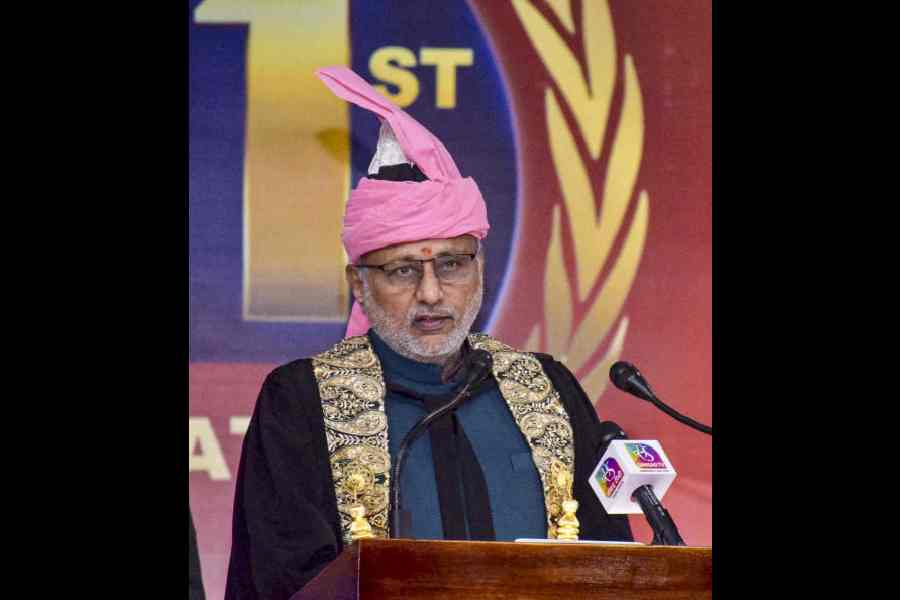

What Jayendra Saraswati did was to expand that space. His extensive networking with the political leaders from beyond the Tamil-speaking zone gave him clout and stature unequalled by any other religious leader. Unlike the Tamil Saivite saint, Adigalar, who forged links with the currents of social reform, Jayendra spoke a language more in common with the emerging Hindu Munani. The revival of Brahmanical cultural symbols and the more-than-nodding acquaintance with militant Hindutva went well together.

Even his bid to play a mediator in 2002 on the Ayodhya dispute was shot through with contradictions. First, he managed to get the Vishwa Hindu Parishad to agree that a court settlement would be binding. Once the organization went back on its word, the seer himself disclaimed any question of building any new mosque anywhere in Ayodhya. Muslims, he told Shekhar Gupta on a television channel, already had nine masjids: why did they need any more? In all this, the bid was to wrest a larger-than-life space for religious leaders. He often expressed the hope that they would solve the Ayodhya dispute if left to themselves. Politics was foul, religion was not. The former connoted division and the latter harmony. Politicians misled India; the men of god would rescue it.

Eventually, the expansion of the math?s own financial clout and public activity exposed deep fissures within. Irrespective of who was or was not guilty of the murder of its former accountant in a temple, it will be a long and tough job reclaiming its older image as a place of reflection, asceticism and study of the scriptures. Religion and politics are often closely inter-linked in Indian public life.

But Tamil Nadu is perhaps exceptional for its long history of militant atheism. This strand was far more significant in the non-Brahmin stirs in the state than in any other region in the country. Karunanidhi is one of the last living links to that other age; for long, Jayalalithaa and her predecessor, MGR, were seen as moving on towards an embracing of religious symbols in public life.

Even in the present controversy, she has disclaimed any intention of taking over the Kanchi math. Tamil Nadu has a minister for Hindu religious endowments and the takeover of such establishments was a major demand of early Dravidian social reform. The power of the state is more central to her vision than the reform of belief. Many forget how the Muslim leader, Palani Baba, was booked and jailed during her previous tenure in office. For much of the Nineties, India saw a slow erosion of secular political space and an increasing role for religious figures in public life. Tamil Nadu was no exception to the trend. It is no coincidence that the VHP, which played a key role in the political recruitment of Lord Ram, was first off the mark in condemning the arrest of Jayendra Saraswati.

What the incident has driven home is a different but more sobering message. Debates on religiosity, social reform or atheism should continue, for they are the lifeblood of a democracy. But the law recognizes no bounds when religion intrudes. Jayalalithaa?s reasons for her timing may be subject to political calculation. But the suspicion of murder is a matter for criminal law. Something in Caesar?s domain should on no account be left to the realm of the sacred.