On May 11, a Supreme Court bench led by Justice N.V. Ramana refused to pass orders to restore 4G internet connectivity in Kashmir. Instead, it directed the grievances to be considered by a three-member committee. With this, the court continues to maintain its approach of evading adjudication where the action of the executive is under judicial review.

In the past, especially during the 1980s, the culture of public interest litigations revolutionized our legal system at two levels. First, it enabled the courts to make substantial interventions in rights issues. Secondly, it provided a platform for espousing the cause of the poor by public-spirited citizens and momentarily enabled access to justice. Thus began an era of intense review of executive action (and inaction). Several rights, such as the right to dwelling (Olga Tellis & Ors vs Bombay Municipal Corporation & Ors. Etc, 1985), the right against forced labour (People’s Union For Democratic Rights and Others vs Union Of India & Others, 1982), the right to speedy trial (Hussainara Khatoon & Ors vs Home Secretary, State of Bihar, 1980), were interpreted to be part of the right to life under Article 21 of the Constitution. From environmental issues to police atrocities, the court nurtured a new philosophy of rights.

One of the first things that we learn in law school about judicial review is that the function of the courts is to adjudicate competing claims of rights. In most cases of rights violation, the State is the alleged violator and the judiciary is the independent organ that examines whether the right is breached. The idea is that courts cannot abdicate adjudication, since its primary task is to assess them and protect fundamental rights.

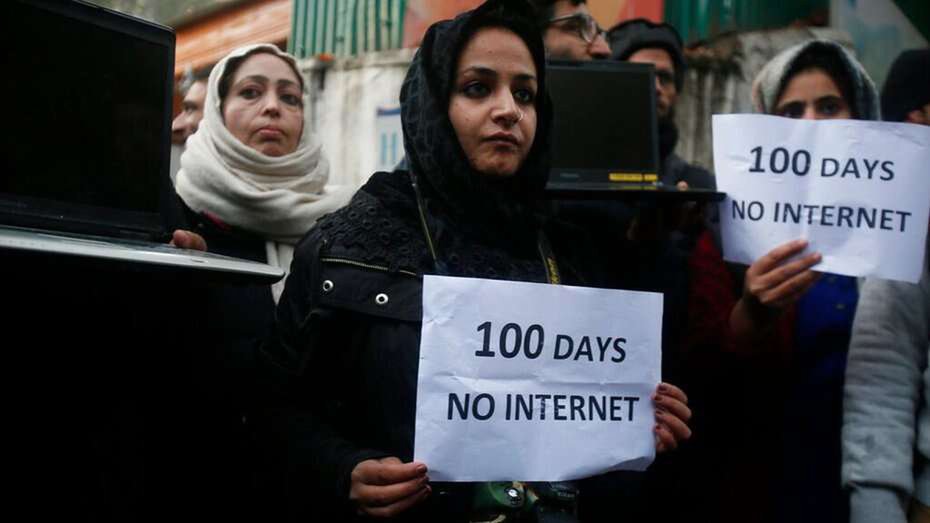

On August 5, 2019, the Central government repealed the special status of Jammu and Kashmir and bifurcated the state into two Union territories. The region was put under a complete shutdown of all kinds of communication, including landline, mobile and internet services. Even 2G internet services remained suspended until March 2020. The shutdown led to a complete dismantling of valuable fundamental rights — of movement, access and expression.

In Anuradha Bhasin vs Union of India and Ors, the communications lockdown was challenged in the Supreme Court. The executive action was challenged on multiple grounds. One of the prominent arguments was that the lockdown fails to meet the four-pronged check in human rights law on the basis of which the validity of State action must be tested. The test requires legality — the existence of a law — necessity of the restriction, proportionality of the restriction, and least intrusiveness — whether the restriction was the least intrusive measure which the State could have imposed. In spite of recalling the test and an elaborate discussion on free speech, the judgment in Anuradha Bhasin refused to interfere with the prohibition on communications. No effective analysis of the legality of proportionality took place. No argument was provided as to why less intrusive measures could not be imposed by the State if at all there is a threat to its interests. The court merely remanded the matter to the executive saying: “the submission of the Solicitor General that there is still possibility of danger to public safety cannot be ignored...” A mere reference to ‘national security’ was enough for the court to sustain the legality of the world’s ‘longest ever shutdown in a democracy’ (The Washington Post, December 15, 2019).

The Covid-19 pandemic has led to major changes in our daily life. Movement has become severely restricted and distancing has become the normal. A significant part of India’s population, at least those who have access, are entirely reliant on internet connectivity for a variety of services such as food or medicines. Students have taken up learning via online classes and courts are operating through video conferencing. When the world witnesses a digital revolution during the fight against a global pandemic, access to high-speed internet remains distant in Kashmir. Patients and pregnant women are unable to get full access to doctors, individuals cannot contact their families and partners, and the society is practically barred from a vital source of information and entertainment. The spread of the epidemic with severe access restrictions, therefore, puts Kashmiris in a precarious position.

Avinash Kumar, executive director, Amnesty International India, said that “The responses to coronavirus cannot be based on human rights violations and a lack of transparency and censorship.” It is in this context that the apex court considered the plea of restoring 4G internet services in Kashmir. But instead of either upholding the validity of the State action (for which the legal basis is shaky) or directing restoration by holding that the executive is wrong, the court has adopted a new technique of deference and delegation.

The court directed a committee to examine the issue — a committee that consists of members of the executive only: secretary, ministry of home affairs, secretary, ministry of communications, and chief secretary, Union territory of Jammu and Kashmir. A whole array of fundamental rights continues to be violated in one part of the country, while the Supreme Court stays silent.

Alexander Hamilton, one of the founding fathers of the US Constitution, said in Federalist papers No. 78, (1787-1788): “the judiciary, from the nature of its functions, will always be the least dangerous to the political rights of the Constitution; because it will be least in a capacity to annoy or injure them. The Executive not only dispenses the honors, but holds the sword of the community. The legislature not only commands the purse, but prescribes the rules by which the duties and rights of every citizen are to be regulated. The judiciary on the contrary has no influence over either the sword or the purse...” Hamilton says that there are always limits to what the court can do since it commands neither military nor economic power. But judicial power is ominous when it evades its paramount task of protecting constitutional rights.