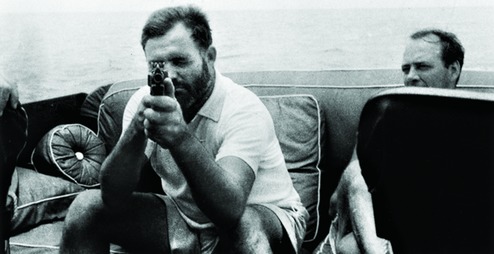

WRITER, SAILOR, SOLDIER, SPY: ERNEST HEMINGWAY'S SECRET ADVENTURES, 1935-1961

By Nicholas Reynolds,

William Morrow, Rs 799

An act of courage, such as fighting a war for a cause, requires true belief. But the aftermath of belief can be troubling.

A recent biography of Ernest Hemingway shows one of the greatest American writers throwing himself headlong into two of the biggest wars of the last century: the Spanish Civil War and the Second World War. His official assignment was that of a war correspondent, but the self-styled soldier was designing his own battles, alongside guerrilla fighters or official battalions, against fascism. The proof of the commitment was in the action.

Yet fascism was not the only reason Hemingway - he called himself a "pre-mature antifascist" - joined war. He also sported a boy's fascination for bloody battles and found them often enough. Nicholas Reynolds's Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy offers an extraordinary portrait of the writer who would later win the Nobel Prize. When he was not yet 20, he had fought in World War I. If he embraced war lovingly, he was equally keen to be a part of the shadowy world of espionage.

What Reynolds really attempts in his book is a coup, by claiming the writer was a "Soviet spy". He was "recruited", Reynolds says, in 1940, and this secret relationship, "one that has been overlooked until now", made the most important difference in Hemingway's life and art, not to mention his death. Reynolds should know. He was a spy himself.

A historian by training, Reynolds worked for the CIA and in 2010, was appointed the historian at the CIA museum ("The Best Museum You've Never Seen"). Reynolds, while organizing an exhibition on the OSS (Office of Strategic Services, the CIA's predecessor) there, came to discover evidence suggesting Hemingway was a spy for the NKVD, which is, what else, the KGB's predecessor.

A Hemingway fan, Reynolds followed the trail and got hold of the summary of the NKVD's file on Hemingway. It said "[Hemingway] was recruited for our work on ideological grounds by [Golos]". (Jacob Golos was an NKVD operative in New York.)

The recruitment forms the crux of the book. Unfortunately, despite Reynolds's scrupulous research, which throws up a wealth of information and presents Hemingway convincingly as a multi-faceted genius and macho man, the premise remains somewhat insubstantial and shadowy, like the world of espionage itself. The story of the recruitment rests on tenuous ground, its records remain fragmentary and the bits and pieces, at least within the book, never add up to any specific reference about Hemingway working for Moscow. One wonders then if the evidence is so flimsy, why a seasoned historian like Reynolds is writing a book about it. Is it because the spy knows things that the researcher cannot speak of?

Instead of overcrowding the book at times with people and facts, Reynolds could also have interwoven Hemingway's writing and personal life - both quite explosive - in these war years. After all, Hemingway got a big book out of both wars - For Whom the Bell Tolls after Spain and The Old Man and the Sea after World War II. And during each war, a new wife too.

But the reader is rewarded in another, more satisfying way, by this otherwise fine biography, written with humour, care and balance. More than the association with the "Russkis" - there is enough evidence that Hemingway knew many influential Russians, including spy chiefs - the book speaks of the faith that the writer placed in Revolution and what it did to him.

The NKVD spy chief in Spain had described Hemingway as "most of all a true believer", not a welcome trait in a potential recruit. From before Spain, where he had fought with the Republicans, Hemingway had identified Stalin as the hope in the war against fascism. To Hemingway, the mass murders did not matter, neither did Stalin's two pacts with the Nazis, as long as the Soviet State did the right thing: spread Revolutions all over the world. Later, while living in Cuba, Hemingway would welcome the "real" Revolution brought in by Castro.

Before that, however, McCarthyism had begun the purge of Communists in America. Though no one asked him, Hemingway tried hard to prove he was no Communist. He kept reminding his friends that he had fought for his country, hunted German submarines in his boat in the Cuban waters, and was on the front, present on D-Day at Normandy. Yet he kept on worrying about what his country's secret records said about him, especially the FB> 's, even if he was the greatest American writer of the day.

The FBI did not once think of looking him up. The drama was taking place inside his mind.

Eventually Hemingway became delusional, seeing FBI agents come to get him, before he shot himself to death. Reynolds's book, if it fails as a spy thriller, becomes a study of a soul in torment.