On this day - August 7 - in 1947 a Dakota rose quietly over warm and humid Delhi. The silver aircraft had taken off from Palam airport wearily, almost wryly, like one of the many tired kites that whirl over that city. Nothing special marked its lift-off, there was nothing beyond a few, very few, handshakes and goodbyes. No guard of honour, no bugles, no heaps of Delhi's favoured flower, the scentless, soulless marigold. But the plane was on an extraordinary voyage and it carried an extraordinary passenger.

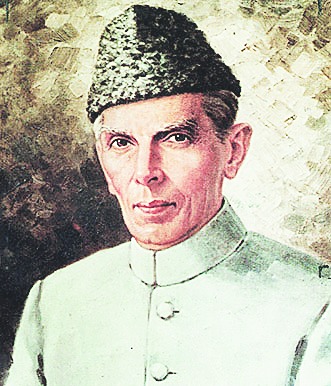

Mohammed Ali Jinnah, the 71-year-old Khoja barrister, his great hour having come at last, was on his way to Karachi which, in a week from that day, was to become the capital of the country that he had created - Pakistan. Its first governor general-designate had just selected Atta Rabbani, a 24 year-old flight lieutenant in the Royal Air Force to be his aide-de-camp. Rabbani recounts that as the plane became airborne, the founder of Pakistan took a long lingering look at Delhi receding into a haze and exclaimed, "That is the end of it." Rabbani says the Quaid remained silent and lost in deep thought throughout the journey. His sister, Fatima, sat beside him.

What might he have been reflecting on? The retributive killings that were to total up to a figure of fatalities "anywhere between 200,000 and 2,000,000"? The largest migration in human history with some 14 million Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs being displaced from their homes and hearts? The patent untenability of East Pakistan with a culture wholly different from that of West Pakistan making the new nation?

Did he ask himself the one political question that millions were asking : "Have we made a mistake?"

Perhaps his thoughts were personal, not political. Perhaps it was "J", as Ruttie Petit, his former wife, now 17 years dead, called him, who was doing the thinking, not the Quaid.

Did the plane fly over Bombay? It may well have done, for it lay right on the flight's path from Delhi to Karachi. If so, J would have fallen even more silent, reflecting on his Malabar Hill home in that city, his only 'true home', the building of which he had supervised "brick by brick", only a decade earlier. Italian stone masons had worked round the clock to complete building it with its pointed arches, stately columns and walnut panelling. But even more than the home, his thoughts could not but have turned to Ruttie, the spectacularly beautiful Parsi "flower of Bombay", niece to J.R.D Tata. Ruttie died on her 29th birthday in 1929. It is said, more perhaps out of willed imagination than hard knowledge, that when Jinnah paid a farewell visit to Ruttie's grave in Bombay a little earlier that August of 1947 he broke down and cried inconsolably - a condition Quaids are not meant for. Ruttie, as they say, was "something". "...When one has been as near to the reality of Life (which after all is Death) as I have been dearest," she wrote in what was effectively a pre-death letter to J, "one only remembers the beautiful and tender moments and all the rest becomes a half veiled mist of unrealities... Darling I love you - I love you - and had I loved you just a little less I might have remained with you... The higher you set your ideal the lower it falls. I have loved you my darling as it is given to few men to be loved. I only beseech you that the tragedy which commenced in love should also end with it..." That letter must have gone through his mind like a knife.

His fellow Kathiawari barrister-politician and Ruttie were on the warmest terms. Did he figure in the Quaid's airborne thoughts? One can only guess but there is little doubt that Mohandas Gandhi would have figured prominently in them.

If the plane's take-off in Delhi was quiet, its landing at Mauripur (now Masroor) airfield in Karachi was tumultuous. And if "that" was "the end of it" in Delhi, then "this" was the new beginning. Welcomers surrounded the aircraft, overturning all protocol arrangements made for the formal arrival. Slogans of "Quaid-e-Azam Zindabad! Pakistan Zindabad!" rent the air as, totally beyond his experience and wholly out of his style, the Quaid found himself being bodily lifted up by "the fervent crowd".

India's dust wiped clean off his boxes, a sherwani steam-pressed for his untypical use, and a cap fitted on a head unused to that constriction, the Quaid went on to make on August 11, 1947 a speech to Pakistan's Constituent Assembly that is remarkable by any standards. Lacking the lyricism of Nehru or the erudition of Ambedkar, it has a tensile quality that is all its own. There are parts of it which could have come from no one other than Jinnah. "...The whole world is wondering at this unprecedented cyclonic revolution which has brought about the plan of creating and establishing two independent Sovereign Dominions in this sub-continent. As it is, it has been unprecedented; there is no parallel in the history of the world... And what is very important with regard to it is that we have achieved it peacefully and by means of an evolution of the greatest possible character."

"Peacefully"? Was Jinnah in denial? Had he forgotten August 16 of 1946 when the Direct Action Day that he promulgated had more than 4,000 dead and 100,000 residents left homeless in Calcutta alone within 72 hours?

In triumphalist self-persuasion he went on to say: "...in my judgement there was no other solution, and I am sure future history will record its verdict in favour of it... Any idea of a united India could never have worked, and in my judgement it would have led us to terrific disaster."

No other solution...? ...sure that history will record its verdict in favour of it...? a united India could never have worked...? That is the TNT - Two Nation Theorist - speaking.

But only a little further down in that speech the TNT vanishes and, in an almost Nehruvian formulation, a self-doubter takes over: "Maybe that view is correct; maybe it is not; that remains to be seen." Followed by: "Now what shall we do ?"

"...[T]he first duty of a government is to maintain law and order, so that the life, property and religious beliefs of its subjects are fully protected by the State." That is not Edmund Burke but Jinnah, August 11, 1947.

"...[N]o matter to what community he belongs, no matter what relations he had with you in the past, no matter what is his colour, caste, or creed, is first, second, and last a citizen of this State with equal rights, privileges, and obligations, there will be no end to the progress you will make." That is not Ambedkar but Jinnah, August 11, 1947.

"You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place or worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed - that has nothing to do with the business of the State." Radhakrishnan? No, Jinnah, August 11 , 1947.

So if that is what Jinnah wanted, what was a separate Pakistan for? What was Partition all about ?

There takes place in all humans, in politicians more than in others, an unceasing contest between vaulting ambition and reason, between blinding ego and proportion. The Quaid's ambition vaulted like a meteor in the moonless night of his ego. But in the 1930s and 1940s his was not the only ego at work. His smaller adversaries matched Jinnah's ego with their own, ferociously. And he could point, with no effort on his part, to the rising tide of Hindu intolerance in the assorted organizations adhering to their own brand of the Two Nation Theory.

The Partition of India is history, tragic history but history. It has had and is having diabolical consequences in terms of terrorism, extremism. The polarization of India is the living monster bequeathed by that history. The two nation theory - TNT - as adopted by the Muslim League under M.A. Jinnah may have worked its way to its culmination in Pakistan, but the two nation theory of the proponents of a Hindu rashtra has not reached denouement. Its goal is not partition but polarization. India must not let a second partition take place in the minds of India's majority and minority populations through the play of a restless ambition and an un-resting ego.

The Quaid-e-Azam is a figure of fascination, both for what he did that was so misguided and for what he thought that was so inspiring. An ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity until the TNT got him; he is an argument for Hindu-Muslim unity and India-Pakistan-Bangladesh collaboration when the TNT slouches to be reborn in the Bethlehem of our suspicions, the Galilee of our ambitions and the Judaea of our egos.

Ruttie's warning to her 'J', must be adapted to read as: "The higher you set your ego, the lower it falls." When J died, his counterpart in Delhi, Chakravarti Rajagopalachari, in a condolence message to Fatima Jinnah, said it all: "Dear Sister, My deepest sympathy and the sympathy of all my people and my government to you and your people. May all of us be enabled by the Most High to go worthily through all our trials and tribulations."