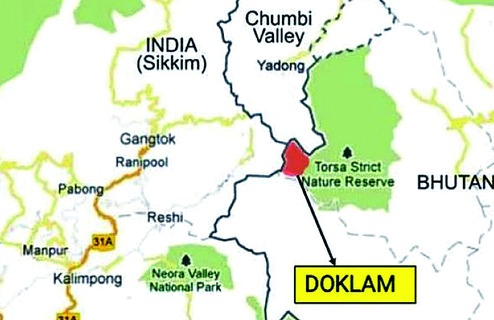

Nestled in a triangular configuration of the Himalayas is the Amo Chu valley and the Doklam plateau, the scene of the latest stand-off during June-July 2017 between the Indian army and the People's Liberation Army of China. Many observers had hastily concluded that an armed clash was inevitable, whereas some others predicted that a border war would break out soon. Brazenly irresponsible warnings emanated from the Chinese side which helped the Indian media, particularly the electronic variety, ascend to a frenzied cacophony. Undoubtedly, the Chinese had grossly miscalculated the Indian and Bhutanese response to their unilateral construction of a road beyond the tri-junction area. The alignment of this road from Doklam was southward, towards the dominating Jampheri ridge in Bhutan that has an influence on the strategic Siliguri corridor. The Chinese road-building venture was halted in its tracks by a rapid build-up by the Indian army at Bhutan's request and as mandated by the Indo-Bhutan treaty of 1949, updated in 2007. The Chinese were taken by surprise and they apparently had no Plan B. As a consequence, there was an element of a loss of face. The sphere for manoeuvring by the Chinese was hemmed in by the forthcoming 19th Peoples Conference, and Xi Jinping did not wish for a border skirmish that would cast a shadow over the grand event. Eventually, the mature political leadership and diplomats of both countries came out on the front foot and defused the tense situation. Having said so, it becomes imperative to demystify the Chumbi valley and the Doklam plateau and to analyse the reasons for Chinese ingress into this area.

Geographically, the Chumbi valley is a wedge-shaped swathe of territory that blends naturally with the cis-Himalayan region of Sikkim and Bhutan. Its topography, altitude, climate and vegetation have nothing in common with the Tibetan plateau. The Amo Chu that flows southwards through this valley eventually joins the Teesta in the plains of North Bengal. As a matter of fact, the main Himalayan range runs eastwards from Pauhunri Peak (22,800 feet) in north Sikkim to the Tangla Pass (16,000 feet) in Tibet and joins the awesome Chomolhari Peak ('Mountain of the Goddess', 23,400 feet) on the Bhutan border and defines the north of the wedge. This range forms the watershed and is the source of Amo Chu. As this tract confers a strategic advantage to the side that controls it, Colonel Francis Younghusband, the leader of the expedition to Lhasa in 1904, and the viceroy, Lord Curzon, had intended to keep it under occupation on a long-term basis after Younghusband's mission was accomplished. The foreign office in London watered down the terms of the Anglo-Tibetan Agreement of 1904 as India's security interests were often overlooked or remained subordinate to those of the British Empire. Imagine Chumbi valley being in India's possession until 1979 for 75 years as per the original agreement! But that is now history.

However, we need to see what impels China to claim territory to the east and south of the Chumbi valley in the Doklam area. From the geostrategic point of view, the low lying valley is dominated on both flanks by high ranges on one side by India and the other by Bhutan. The area up to Yatung - an important nodal town - about 25 kilometres, and those beyond it are under effective observation from the Indian and Bhutanese frontiers. One has only to climb the Gyemochen Peak (15,000 feet) between Jelep La and Doka La passes to get a magnificent view of the entire area. This factor has obvious tactical and strategic operational implications. Hence China is determinedly endeavouring to expand the base of the inverted triangle at Doklam which, at present, is only 10-15 kilometres wide. Besides that, the Chinese are claiming territory which is located on higher ground and in greater depth towards the Jampheri ridge to compensate to some extent its existing tactical disadvantages and, at the same time, to put psychological pressure on India by inching closer to the Siliguri corridor. Having gradually taken possession of parts of the claimed eastern shoulder of the valley, the Chinese have not only gained tactical depth for the highway leading from Yatung to Lhasa that was hugging the Sino-Bhutanese boundary but are also able to exert more pressure on Bhutan as they are now closer to Paro, the royal stronghold in western Bhutan. In this area, the Chinese have also denuded a large part of the dense pine forests for timber, which is a scarce resource in Tibet.

Contrary to some reports and analyses of a build-up on the Chinese side, the present situation in the Doklam sector is normalizing. On March 5, 2018, the defence minister, Nirmala Sitharaman, stated in Parliament that there has been a redeployment of troops of both sides and force levels have been reduced. There is no doubt that the Chinese have erected shelters and stationed vehicles, including earth-moving machinery, for use by their troops as can be seen in satellite coverage of the depth areas. Besides that they have constructed some helipads, gun pits and defence fortifications for their security. It must not be overlooked that most of these developments are defensive in nature and made for their troops to sit out the severe winter season as the 15,500 feet Tangla Pass gets closed due to heavy snowfall. The steep slopes and rocky terrain in the Chumbi valley preclude the use of armoured vehicles. Hence reports indicating the presence of tanks were grossly out of sync with reality. Erecting watch towers in lowlying areas are pointless and mistaking sentry posts with them is ridiculous. The lack of professional competence in the interpretation of satellite or aerial photography is evident from the hurriedly concluded reports and assessments that have appeared in the media. Many 'security experts' have also faltered in this regard. The basic factor is that the terrain on the Chinese side of the frontier in the Chumbi valley does not lend itself to be a launch pad for offensive action as the Indian forces are occupying commanding heights facilitating observation during day and night. The severe drubbing and heavy casualties suffered by the Chinese in the skirmishes and artillery duels in the Nathu La area during 1967 would not have been lost on the PLA. It is creditworthy that since then not a shot has been fired by either side anywhere along the 4,067 kilometres border, although at some places tense standoffs have been taking place where jostling bouts were resorted to by the troops as it happened in Doklam. These local issues were amicably resolved by border meetings and diplomacy. However, prudence demands that Indian forces should remain alert along the entire border, particularly in areas where the Chinese troops are located in tactically advantageous positions.

India-China relations assume the greatest significance for stability, peace and prosperity of the region. It bears no reiteration that together we make up a third of mankind. The leadership of both nations, despite hawks on both sides of the Himalayas, realizes the significance of peace in the region for them to fulfil the aspirations of their people. We may be competitors but are not rivals and have a 'shared vision for the 21st century' along with a 'strategic and cooperative' partnership. While it is important that we keep in mind the lessons of the past, we must not allow the acrimonious decades of the late 1950s and the 1960s to cloud our judgment and hold hostage a promising future of our billion people. As an emerging power, India should engage China with self-confidence and on an equal footing. While it is a fact that China has progressed enormously, it merits recognition that India, too, is no longer the India of 1962.

The author is former chief of the army staff and former governor of Arunachal Pradesh