The opening notes of Sagar Sen singing Ei jeebon emni kore were being played on the sound system when it developed a snag and stopped. “Take two,” singer Antara Chowdhury called out in jest, aping a recordist’s call for a fresh attempt after a cancelled bid.

The joke was on point. The venue for the small gathering was the recording studio of HMV (His Master’s Voice) in Dum Dum, also aptly described as “Bangla sangeet-er tirthakshetra” by Debashis Basu, who was compering the event. The walls had pictures of the doyens of both Indian classical music and popular music. They have all recorded here.

The studio was designed by a team of acoustic engineers from London which had designed EMI (Electrical and Musical Industry)’s Abbey Road Studio as well, revealed sources at Sa Re Ga Ma India, which now owns the heritage music company.

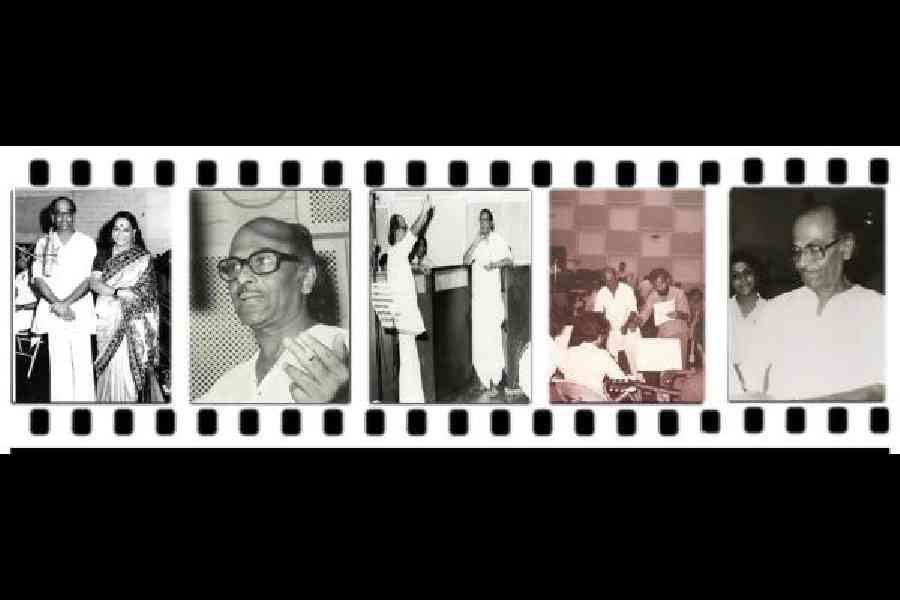

The Jessore Road studio, that is itself a few years shy of a century, was hosting a tribute to a composer who is turning 100 later this year — Salil Chowdhury. A calendar was being launched in his honour, featuring photographs, posters and booklets of films he had composed for — Do Bigha Zameen, which hailed his entry to Bombay, his other early films like Biraj Bahu, Naukri and the milestone Madhumati, Kabuliwala and Half Ticket from the 60s.... “The Kishore Kumar-starrer had flopped initially but was a big hit when it released later,” said Sudipta Chanda, a poster collector and music fan who has produced the calendar drawing on collections both his own and of other collectors like Vishwas Nerurkar, Debasis Mukhopadhyay and Paramananda Chowdhury. The calendar features posters of his Bengali film hits too — Marjina Abdallah, Lal Pathor, Sister....

Mukhopadhyay recalled wondering why a portrait of Chowdhury featured on the wall of Calcutta Academy on Amherst Street beside pre-Independence icons. “On enquiry, the school headmaster told me that Chowdhury was admitted there in Class III.”

He had also visited

21 Sukea Street, mentioned in his autobiography Jiban Ujjiban, where he spent his childhood, he said. Chowdhury’s cousin Nikhil Chowdhury ran an orchestra club called Milan Parishad. Young Salil used to hear and repeat the tunes alone on the roof which his cousin overheard and got him to join the club. The youth learnt playing all the instruments there and accompanied the Milan Parishad band to Chhaya cinema in Maniktala. “Silent films would run there and, seated behind a screen, he would play the piano with the band in accordance with the visuals on screen. May be that was his initiation into music based on film situations,” he reflected.

The musicians invited at the launch had themselves recorded in the studio. Guitarist Soumya Dasgupta, son of composer Sudhin Dasgupta, said he was stepping in after four decades. “Events are usually not allowed here.”

Guitarist and arranger Rocket Mandal recalled praying for half an hour when he had to record with Chowdhury. “Salilda’s chord progressions involved cross-fingered movement which was as sweet on the ear as it was tough to play,” he said.

A page from the centenary calendar on Salil Chowdhury

Debajyoti Mishra, another long-time associate, pointed out that Chowdhury’s music was not just about symphony and harmony. “Salilda could visualise on an epic scale and his heart always beat for labourers. Even in a story from Arabian Nights (Marjina Abdallah), he included a woodcutters’ song, O bhai re bhai. He worked with great storytellers, who patronised his vision, be it Dinen Gupta in this case or Ritwik Ghatak, Mrinal Sen, Bijan Bhattacharya... Salil Chowdhury refused to stagnate. Ei roko prithibir gari ta thamao is like a prayer song to me in which he says he would travel to a different planet if he stagnated on earth,” Mishra said.

Antara appealed to all to come together to preserve Chowdhury’s work. “His music needs to be studied as Salil sangeet,” she said, sharing her plans for the centenary year ahead.