Since films are a series of photographs run together fast so that we can discover a narrative in them, a single photograph of a scene — a freeze-frame, so to speak — can capture a moment from this narrative for eternity. But to mirror the cinematic mood of a moment from a film in not a still from the movie but a photograph of the scene being rehearsed takes a rare talent, something that Nemai Ghosh was blessed with. Think of that scene in Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne where Goopy and Bagha are in the bnaashbon and a tiger wanders in. The mood and the music are thick with tension to the point of being stifling. Ghosh’s first-ever shot of Satyajit Ray was around this time, along with Tapen Chatterjee and Robi Ghosh. The three men (Ghosh has his back to the camera) are seen framed by a gap between two trees. The striations made by roots on the trunks in the foreground are visually paralleled by the three men standing and the bamboo trees visible behind them, tricking the eye into travelling lengthwise from the light filtering in above the subjects to the dense, darker lower half of the image where the action is. This evokes a similar sense of action as the film and this is the opening image of the show, Light and Shadow: Satyajit Ray Through Nemai Ghosh’s Lens (organised by DAG and on view at the Alipore Museum).

Some viewers would not be wrong to experience a sense of déjà vu upon venturing into the exhibition for Ghosh’s photographs of the maestro — Ray called Ghosh his Boswell with a camera — are familiar to Calcuttans, having been the subject of several photography exhibitions over the years, not to mention books and newspaper articles. But what is interesting is that the venue of the ongoing show, Alipore Museum, is not a traditional art space visited only by Bengali connoisseurs but also by many others for whom Ghosh’s vision of Ray and the people who enlivened the magical worlds he conjured was a revelation. Thus the viewers’ excitement on discovering a candid photograph of Smita Patil with a telephoto lens aimed at Ray or a more sombre side to Utpal Dutt — who they had only seen in Gol Maal until then — from Jana Aranya was revealing.

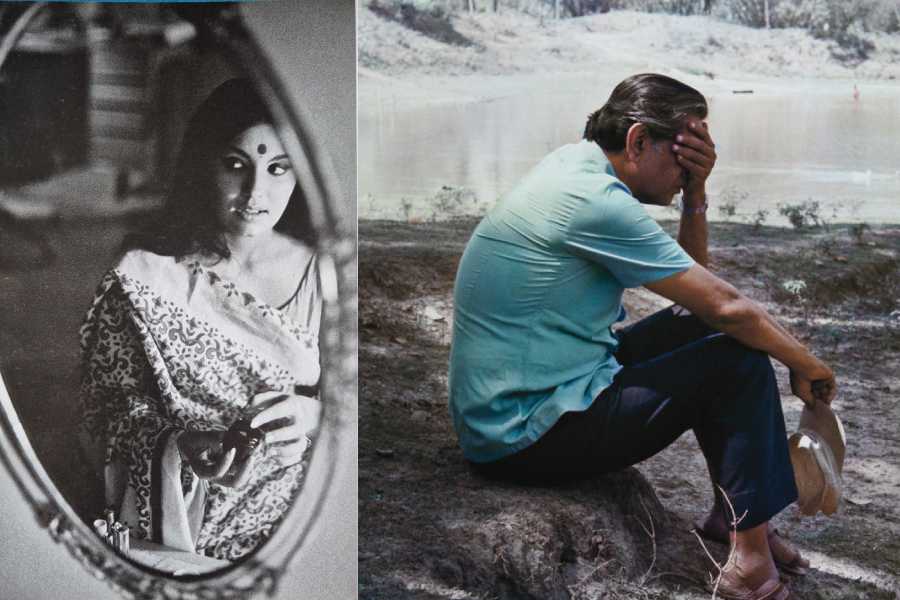

Ghosh’s photographs are invaluable not only because they serve as a visual narrative that chronicles the journey of Indian cinema but also as mirror photography’s philosophical engagement with, and its momentary failures to illuminate, the mysterious, shifting, lines that ostensibly separate reality from illusion. A still from Seemabaddha shows the actress, Parumita Chowdhury, gazing at an oval mirror (picture, left). The exchange that takes place in this intensely private moment remains elusive to the photographer, revealing the camera’s occasional limitation as a tool of inquiry in a world made more of shadows than light. Yet, in another such shot, Ray — who is usually facing Ghosh’s camera, his face revealing the inner workings of his mind — sits alone and slightly hunched over in the shade of a tree with his face buried in his palm (picture, right). Even though the camera and the viewer cannot see his face, the camera, in this instance, has clearly captured and conveyed the maestro’s mood.