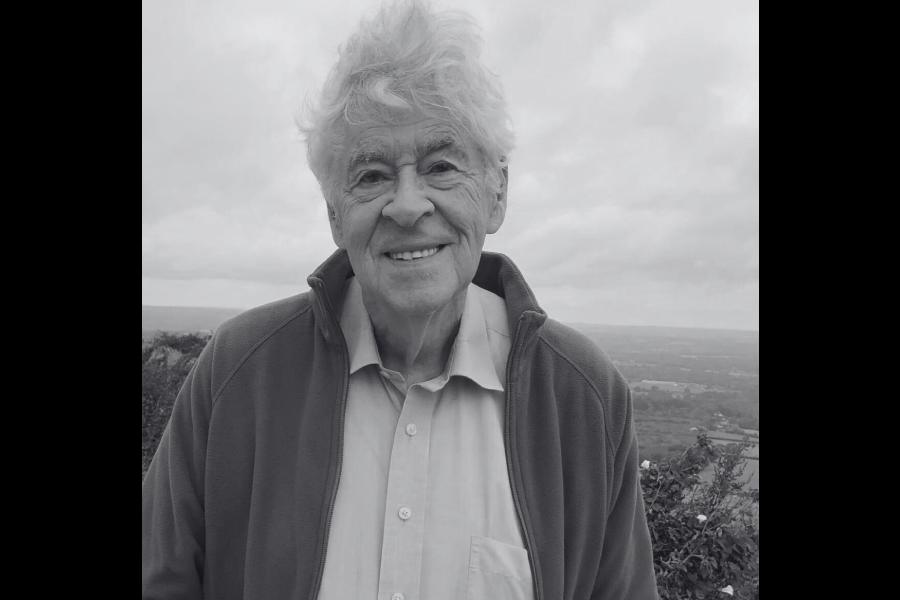

A chance meeting with Jeremy Seabrook in Calcutta in the summer of 2001 changed the trajectory of my life.

That evening, map of Calcutta in hand, the 60-year-old cut a hassled figure in the middle of central Calcutta’s chaotic traffic. He was trying to hail a taxi but to no avail.

I offered to help and he agreed. Before he got into the taxi, he shook my hand, introduced himself and asked me what I did for a living.

At the time Jeremy was a columnist with The Statesman where he was known by one and all as a “great writer and the voice of the poor and marginalised”. Upon hearing that I was freelancing for the same publication, he asked me to visit him at the guest house where he was staying.

The next morning I reached the guest house. I had taken along all the reports I had filed for the newspaper. Would he like to see them? He would. And he did. Jeremy went through them one by one and with great interest.

When I told him I was the first graduate from a family of subsistence agricultural workers and passionate about journalism, he encouraged me to tell him my story.

I told him about my birth in an impoverished village in Uttar Pradesh where my parents continued to live. Neither of them had received any schooling. I studied in a madrasa and later my maternal uncle, who was living in Calcutta, offered to take me in so I could continue my education.

My story resonated with Jeremy. He was the first person from his family to go to university. His own family members had worked in shoe factories in his hometown in the Midlands, England. They tied knots in the threads of machine-finished shoes or swept leather waste from under the machinery.

His mother, who was the youngest of many siblings, had completed her schooling. And she tried to realise many of her own thwarted dreams through him.

By the end of our conversation, a bond had been struck and gradually it blossomed into a lifelong friendship.

Jeremy told me he wanted to write about me and his own experiences as both of us had similar backgrounds. He told me when he started to write about the downtrodden, his mother expressed no pride but indignation: “I have worked all my life so you would never know poverty. Why must you harp on that? Why can’t you go and get a proper job.”

Next week, he dedicated his weekly column to our shared experiences and put my name alongside his own.

He wrote: “There is always something poignant in the fate of children from poor families who become educated. It can be distressing when those to whom you are attached by blood and birth become cultural strangers: for this is what education actually means to the children of the poor. It involves transition into a quite different culture; to such a degree that the process often sets up torn loyalties, confusion over social identity, and impatience with the affection bestowed by loving but uncomprehending hands.”

Within a few months, I landed a job as a trainee reporter in the newspaper. Jeremy took me under his wings and I grew beyond what I believed I could ever achieve.

Jeremy moved back to London. We started to write to each other; first, letters, then e-mails. He visited Calcutta again in 2006. By then I had changed jobs and was working as a senior crime reporter with The Telegraph. One day, he said he would like to visit the slum in Kidderpore where I lived.

I agreed. As a faceless boy raised in a slum, I had developed a strong network with my ilk there.

After a few days, Jeremy suggested we could explore the idea of writing a book on the addresses of the city’s most impoverished people. The Telegraph granted me a month’s leave and soon we started travelling the length and breadth of the city’s slums. We collected countless stories of discrimination and injustice.

Jeremy acknowledged my networking within the slums which had helped us complete the project.

The book, People without History (Pluto Press, London), was published in 2010. By that time, I had shifted to Delhi.

In 2012, Jeremy visited Delhi and for the first time, he met my wife Ayesha and our two-year-old son Abaan. This would be the last time we met in person, it was the last time he visited India. However, we remained in touch.

He would send my son books and during the pandemic, helped him with his English. In 2024, when the boy topped his school in English in the Class X boards, Jeremy was ecstatic.

It so happens that Abaan shares his birthday with Jeremy.

And that’s just one of the countless ways in which me and mine will always remain connected to Jeremy Seabrook.