Ghatakpukur is a fisheries hub in South 24-Parganas, 30 kilometres from Calcutta. It supplies the city with a generous volume of its green produce. “But all that is now,” says Faruque Ahamed. The 43-year-old continues, “When I was young, people avoided coming to Ghatakpukur; it was a den of criminals. It was a village, not even a town. Murder, rape, theft... you name it. Small and big dhabas used to sell liquor, drugs.”

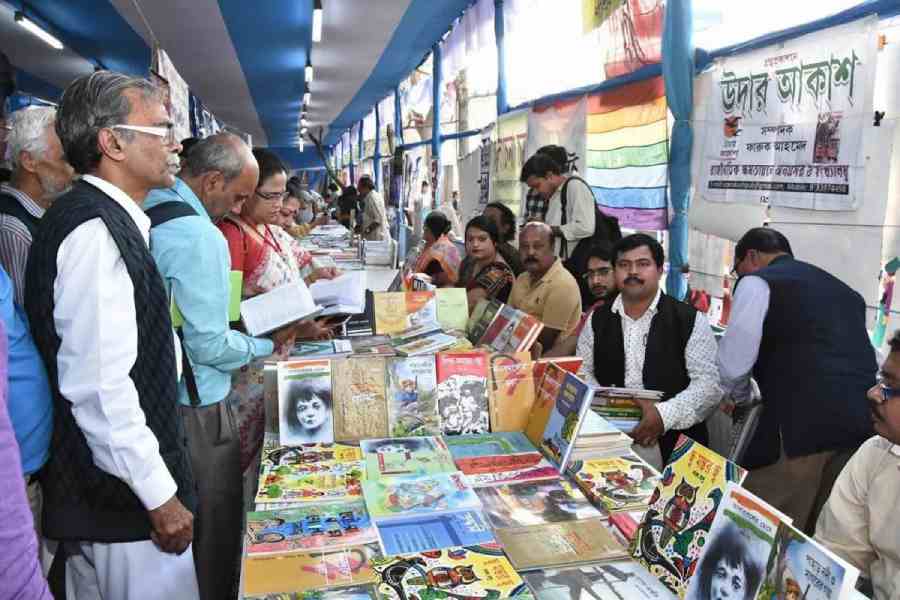

Not quite the ideal cultural milieu. But Ahamed, who is now a research scholar in the history department at Kalyani University, has been publishing Ghatakpukur’s first and only magazine Udar Akash since 2002.

Udar Aakash magazine, Ghatakpukur

Udar Akash means the generous skies, and here were people without even rock solid ground beneath their feet. Ahamed wanted to fix this. He says, “If you want to change society, you will have to educate young minds. My village did not have an environment where children could study. And those few who did, they had no motivation.”

Ahamed was not the first to think of a magazine for Ghatakpukur. The idea first occurred to librarian Rafiqul Islam. He even started one called Dhansiri in 2000, but the effort didn’t survive beyond two issues.

At the time, Ahamed was still in school; he had even written for Dhansiri. Two years later, when he was in the second year of college, he took up Rafiqul’s unfinished dream.

He tells The Telegraph he knew that to sustain a magazine from a place like Ghatakpukur, it was essential that he involved the people of the area. The editorial for the first issue was an appeal to the people of Ghatakpukur — to be more humane.

Ahamed’s life’s story, Udar Akash’s ambition, all of it is entwined with the story of Ghatakpukur’s past. It is not always possible to separate the threads, but it is impossible to miss the connectedness. Ahamed says, “In my childhood, there was only one school each for boys and girls. Children would come from neigh-

bouring Bhangar, Polerhat, Baroli, Paglahat, Jagulgachi, Gobindapur, Nalmuri. Even then, the girls’ school would be filled with rows of empty seats.”

He continues, “The boys dropped out when they were 14 to 15 years old. Girls were married off. Child marriage was not looked down upon. Boys worked as labourers in other districts of Bengal. Some worked as daily wagers at the brick kilns in and around Ghatakpukur. Many would migrate to other states in search of a livelihood.

Education was on no one’s priority list.”

Ahamed’s father was an ayurvedic medical practitioner. His lone income was not sufficient to support Ahamed’s education. Says Ahamed, “When I was young, I used to work as a farmhand and did odd jobs to earn money, fund my own education. All along, my father encouraged me.”

Some dreams have a life force of their own. Ahamed says he always wanted to be a writer, a poet. “It might sound ambitious, but when I was in Class IX, I started writing poetry. I used to dream that I would publish them one day. I used to keep aside my tiffin allowance just for this.”

Back to Udar Akash. The idea behind the magazine clicked. Says Ahamed, “The people of Ghatakpukur were delighted to have a magazine that told their story. It was a call for everyone to wake up from their slumber.”

People responded. Poems and prose were published. Ahamed rattles off names of contributors — Lalmia Molla, Ikbal Alam, Sabina Begum, Alamara Khatun, Abdur Razzak… To an outsider, the names might hold little significance, but to the people of Ghatakpukur, they were respected figures. Their names raised the profile of the magazine.

Ahamed continues, “With the help of my readers, we approached the administration to close down liquor shops. People also vehemently opposed the sale of drugs in the area.”

The community intervention powered by Udar Akash brought about other changes. Child marriage was prohibited. Attendance in the girls’ school increased. More schools came up.

Women started sending in stories, essays, and poems for the magazine. Faruque persuaded young women like Julekha Sultana to write. She was an undergraduate student when her first poems were published. “I haven’t looked back after that. My poems are now published in other magazines too, but Udar Akash was the window,” says Sultana.

With time, the magazine gained greater popularity. “Well-known writers such as Shankha Ghosh, Joy Goswami, Tilottama Majumdar, Khajim Ahmed and Nalini Bera wrote for Udar Akash. The more they wrote, the more the people of Ghatakpukur became confident that education is the way forward,” says Ahamed.

Today, Udar Akash is no longer just a magazine. It is a cultural platform, according to Ahamed. He conducts cultural programmes, quiz contests, debates and group discussions in the neighbourhood library. He also owns a publishing house. From the earnings of Udar Akash, he has helped students complete their higher education; Sonali Khatun did her postgraduation and so did the visually challenged Osnai Shaikh.

Ahamed says, “The magazine is an effort to raise awareness among the people of Ghatakpukur and to encourage young minds to study, to channelise their positive energy.

Udar Akash is another name for opportunity. If you have dreams, we will fulfill them.