That day I returned home from college perched on the open roof of the bus and discovered Jadavpur afresh...

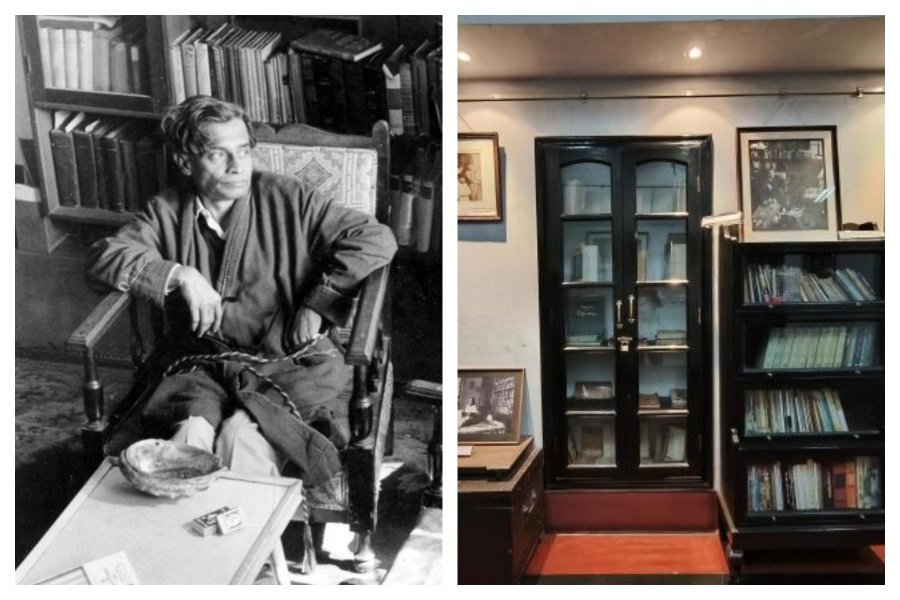

Nothing special about these words you might say. But what if one were to point out these are from a letter, from the 1960s, from a father to a daughter, the father is the illustrious Bengali poet Buddhadeva Bose and the addressee, Damayanti Bose Singh.

The words and their conjuring recall one of Bose’s literary concepts, “chalti muhurter kabita” or a poem of the immediate present.

“The poetry of the present as D.H. Lawrence called it,” says Rosinka Chaudhuri, who curated the Calcutta exhibition titled Bringing an Archive to Life: Celebrating Buddhadeva Bose.

At the exhibition, hosted at the Jadunath Bhavan Museum and Resource Centre on the poet’s 116th birth anniversary, the poet’s letters are among the many things on display.

There is one from Dorothy Pound, wife of the American poet Ezra Pound, to Bose, dated August 1953. Pound was in St Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington DC. Dorothy helped set up a discreet meeting between Bose and Pound. She writes, “I am at St Elizabeth’s... to take EP (Ezra Pound) out into the garden. Hoping this will reach you. You will get lost unless you take a taxi there. It is across the river...”

Chaudhuri’s footnote: “Dorothy Shakespear Pound was an English artist involved with the Vorticism movement. She married Pound in 1914. But in the late 1940s with the end of World War II, Pound was charged with treason. He was imprisoned on grounds of insanity in Washington DC and later assigned to a lunatic ward in St Elizabeth’s Hospital.”

There is Bose’s correspondence with the Bengali poet Sudhindranath Datta, including the one in which he discusses Gerard Manley Hopkins’s concept of “sprung rhythm”. Datta had in a series of letters to Bose in April of 1946 talked of its meaning, its application in Bengali verse and Amiya Chakrabarty’s use of it.

Possibly in reply to one such missive, Bose writes to Datta: “The other day I was thinking that perhaps it is possible to write sprung rhythm in Bengali poetry too.” He goes on to suggest ways of doing it while encouraging Datta to give it a try.

A letter from American writer and linguist Edward C. Dimock from the University of Chicago, US, shows the great attention with which he went through Bose’s manuscript of the play titled The Hermit and the Courtesan. It is Bose’s translation of his own Bengali work Tapaswi o Tarangini. Bose received the Sahitya Akademi Award for it in 1967.

Dimock, a scholar of Bengali literature and South Asian civilisations, wrote to Bose: “I went over the Bengali original very carefully, and your translation equally carefully, and I must say I am delighted. The translation captures the music of the original most effectively, and combines both clarity and a certain flavour of Indianness which is most appealing.” He thereafter lists some of his observations regarding the text, and usage of certain words keeping in mind the Western audience.

There are more letters. For instance, singer Rajeswari Datta’s letter to Bose. She writes to him from Cambridge telling him how she remembers the evenings spent with him and Rumi, his younger daughter, when she visited Calcutta. Rumi is Damayanti’s dak naam. Rajeswari also discusses the politics of those times. She thinks aloud in her letter about the impact of the Naxal movement on the colleges and universities of Calcutta, and how the city would fare under the United Front government.

An illustrated postcard from American author Henry Miller, also addressed to Bose and dated May 2, 1967, elaborates on the former’s familiarity with Rabindranath Tagore since he was 19 or 20. Miller writes that he heard Tagore speak at Carnegie Hall “either before or after World War I”. The cover of the postcard is a reproduction of a painting by Henry Miller.

But the most endearing of all Bose’s correspondence remains the exchanges with his beloved daughter.

In one such, he laments how he has run out of his regular black ink and will have to fall back on Sulekha, a popular Indian brand. The poet also provides a detailed diet chart for Rumi when she is a newly arrived student at Indiana in the US. He regales her with news from the department of comparative literature at Jadavpur University.

The month-long exhibition is a collaborative effort of the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences (CSSS) and the School of Cultural Texts and Records, Jadavpur University. Damayanti donated the author’s collection of books to Jadunath Bhavan in 2011.

It was Damayanti who approached the CSSS with the request that her father’s entire library, as it existed in his study at Naktala, find a place among the Special Collections of Jadunath Bhavan.

You could say, like a poem of the immediate past.