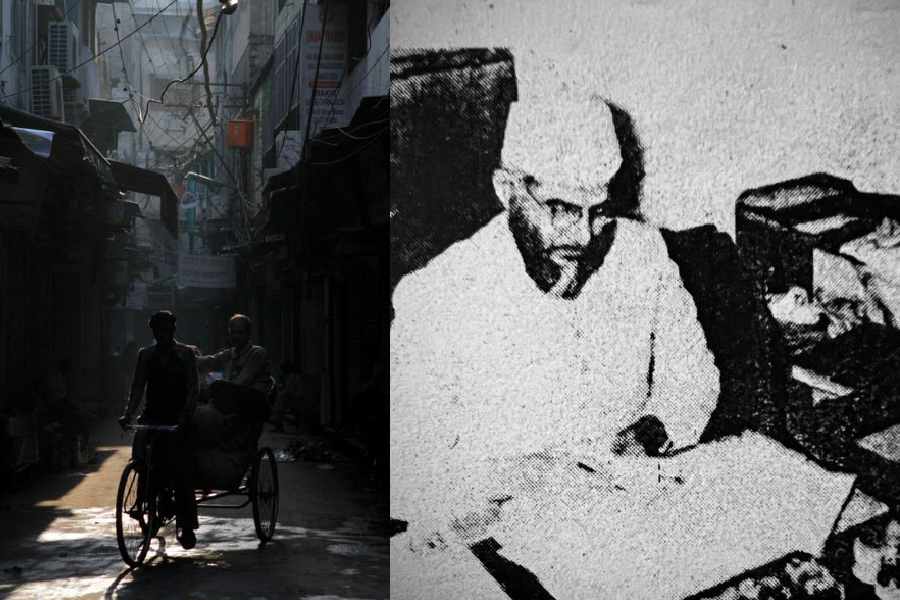

In those post-Partition days, there were unseen borders drawn in old Delhi — what in today’s parlance is called Delhi-6. There were Muslim and Hindu areas within the same lane. Haveli Hesamuddin in Ballimaran was the mohalla (locality) of a prosperous Muslim business community called Punjabis or the Shamsi baradari. It was, therefore, in common parlance known as ‘Punjabi Phatak’ (Punjabi Gate). In reality, they were not Punjabis, but had migrated from Central Asia; they were very fair-skinned, some of them had blue eyes and blond hair. None of them spoke Punjabi. Most of them owned shops and businesses in Chandni Chowk and Sadar Bazar. Many of them owned large showrooms and hotels in Connaught Place and Kashmiri Gate, with palatial houses in Civil Lines, which was at that time the most expensive and posh residential area of Delhi. Our family was one of the few non-Punjabis living there, and was looked upon with suspicion. The government and administration allotted us a house that belonged to a prosperous Muslim family that had migrated to Pakistan….

…In the 1950s, Ballimaran was in great turmoil, and undergoing significant demographic and emotional changes. While some prominent families had migrated to Pakistan, others were gravitating to this place from different parts of India. It emerged as the hub of new post-Partition Muslim politics and cultural renaissance. Things were changing, and education was becoming popular. Mohani shifted to our mohalla, and brought all the writers, poets, revolutionaries and freedom fighters with him. Ballimaran was known as the Mohalla of Mirza Asad Ullah Khan Ghalib. With Mohani also spending his last days here, it became a centre of activity for all those with patriotic zeal and revolutionary ideas. Prominent journalist Kuldip Nayar, who migrated from Lahore, came here to spend time with Mohani and practise Urdu journalism. Famous poet Josh Malihabadi, whenever he was in Delhi, preferred to stay here. Theatre practitioners like Habib Tanvir and Baba Niaz Haider found refuge in Haveli Hesamuddin and Ballimaran.

When Abba decided to resign from Aljamiat and launch a daily newspaper Nai Duniya in 1951, the ground floor of the haveli was converted into a newspaper office. For some time, we lived on the upper floor of this two-storey house, but later shifted to a house next door. The upper floor, with large rooms and enormous terraces, became the refuge for those who had no place to go. Nai Duniya was an evening newspaper, so all office work was over by the afternoon. After that, the whole office, its courtyard and terraces were available to idealists, culturally adventurous political mavericks, revolutionary young men, and the most outspoken journalists to spend their time there.

There would be rehearsals for a play on one terrace, while impromptu mushairas would be organized on the other if Jigar Moradabadi or any other famous poet were visiting the city. While Communist Party members would have heated debates on the class character of Nehru’s government in one room, in another, some ulema would plan relief work for some place where a communal riot had broken out. From Habib Tanvir and young M.F. Hussain to poets like Gulzar and Zubair Rizvi, many creatives spent their time in the Nai Duniya office. There were dozens of cots (charpai or khat as we call them in Hindustani) on the terrace. Anyone could sleep there, and have a cup of tea and nahari-roti for breakfast. Thus, in my growing years, my young mind was exposed to the most exciting and dynamic melee of ideas and cultural cocktails possible.

In 1952, a young woman called Sarla Gupta, who belonged to a prominent family of Delhi lalas, and lived in Haveli Hyder Quli in Chandni Chowk, came to meet Abba. She wanted to contest the municipal corporation elections from Ballimaran on a Communist Party of India ticket. She had just graduated from Delhi University, and was burning to change society and build a new India. It was unthinkable for a communist to contest and win from a predominantly Muslim constituency, and that too when the candidate was a young woman who had just graduated from university.

Muslims, who had been divided between the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League before Independence, believed that in independent India only Congress could help and protect them. Even those who harboured a dislike for Nehru, Azad and Patel now looked at them as their saviours, and voted for Congress.

They looked at the Hindu Mahasabha and the newly formed Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS) with suspicion and fear, apprehending that if these parties came to power, they would marginalize them and treat them as second-class citizens. They regarded any third party as ‘vote katwa’ (divider of their votes), which would ultimately help parties like the Hindu Mahasabha and BJS, which were trying to gain a foothold among Hindus in the post-Partition atmosphere of suspicion and hatred.

Abba’s undeniable spirit pushed him forward, and he agreed to back Sarla Gupta. She defeated the powerful Congress candidate with Abba’s support. It was a prestigious election for Muslim Congressmen, and a test case inasmuch as it was the first post-Partition election. This made the Congress government extremely wary.

Govind Ballabh Pant, a freedom fighter, close confidant of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, and the first chief minister of Uttar Pradesh from 1946 to 1954, was highly wary of communists, and regarded them as dangerous for the country. Sarla’s victory from a Muslim area was exaggerated to foment the fear that Muslims were gravitating in large numbers towards the communists. Some rightist Hindu organizations saw this election as a massive conspiracy — a political takeover of India by the communists with the help and support of Muslims. In the aftermath of the Partition when most Muslim leaders, even progressive ones, had left Indian Muslims in the lurch and migrated to Pakistan, the latter had no one to look up to or raise their voice, and believed that democracy was not meant for them, but only for the Hindu majority.

Reproduced with permission from I, Witness; by Rupa Publications