There have been other blockbuster shows of Mughal art. But this one is on steroids. To begin with, it brings together more than 120 super-star pieces produced under the rules of Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan (1556-1658), each selected for its outstanding aesthetic qualities; there is nothing second tier. Next, it is held at the V&A in London, so the show’s curators have mined its own astounding holdings of Indian art to put some pieces on public view for the first time, while showing much-loved favourites, such as Mansur’s painting of an exotic zebra given to Jahangir. Next, the V&A’s Indian department has exceptional relationships with great collectors worldwide and for this show Sheikha Hussah Sabah al-Salim al-Sabah has lent some of her best pieces, such as the jewelled dagger made in Jehangir’s court workshop.

A jewelled dagger made in Jehangir’s court workshop Victoria and Albert Museum, London/The Al Thani Collection/Prudence Cuming Associates

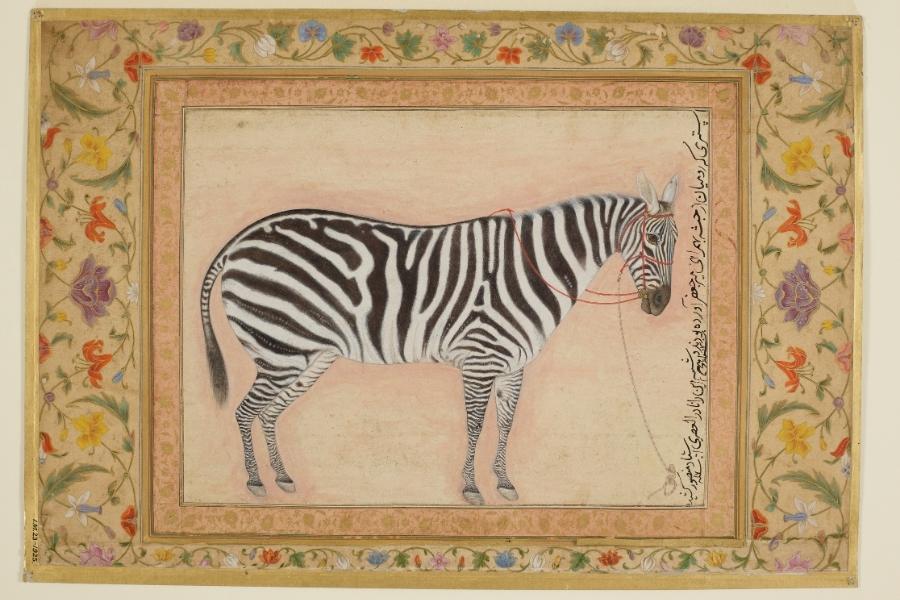

However, such is the nature of Mughal art and its requirement for close, considered, intense looking and study that the whole show cannot be absorbed in one visit, not even by a seasoned student of the subject. Also, it is no good thinking you can buy the catalogue first and do your homework: there isn’t one. But there is a companion book, which is well worth the advanced investment (it’s expensive, and there is no cheaper paperback edition – why?). Following Rajeev Kinra’s accomplished introduction, full of insights, there are 18 essays. Those concerned with Akbar’s reign include Hugo Miguel Crespo’s on sharp Portuguese gem traders, and Ursula Sims-Williams’ unexpectedly gripping analysis of the 34 seals and inscriptions on a Qur’an from the Imperial library. Susan Strong – curator of the show and editor of the book, takes us into the rarified world of Jahangir’s court and its rituals, while Peter Jarman explains the busy trading and gifting that satisfied these emperors’ fascination with exotic animals which, real and imagined, decorate their album leaves or are given full-sized portrait paintings; a turkey cock from Goa, coconut lorikeets from the Moluccas, Jahangir’s zebra from Ethiopia.

A zebra presented to Jahangir, by Mansur, 1621. Opaque watercolour and gold on Paper Victoria and Albert Museum, London

It helps that the show is organised into three sections, one for each emperor (making three visits to the show an ideal strategy), and explores two clear themes: the creation and evolution of a distinctly Mughal art, and each ruler’s very different and very lavish use of art for political, propagandist or diplomatic purposes, or sometimes just for pure pleasure. If it tweaks your curiosity, then hurry to secure a place for the conference on 27 and 28 March.

But if you can only have one shot at it — one whole day with time out for the occasional sandwich and cup of tea to refresh your eyes, no hanging about — then here is my personal, rigorous selection of unmissable treats in the first part.

A triple portrait of Akbar handing his crown to Shah Jahan with Jahangir looking on Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Chester Beatty

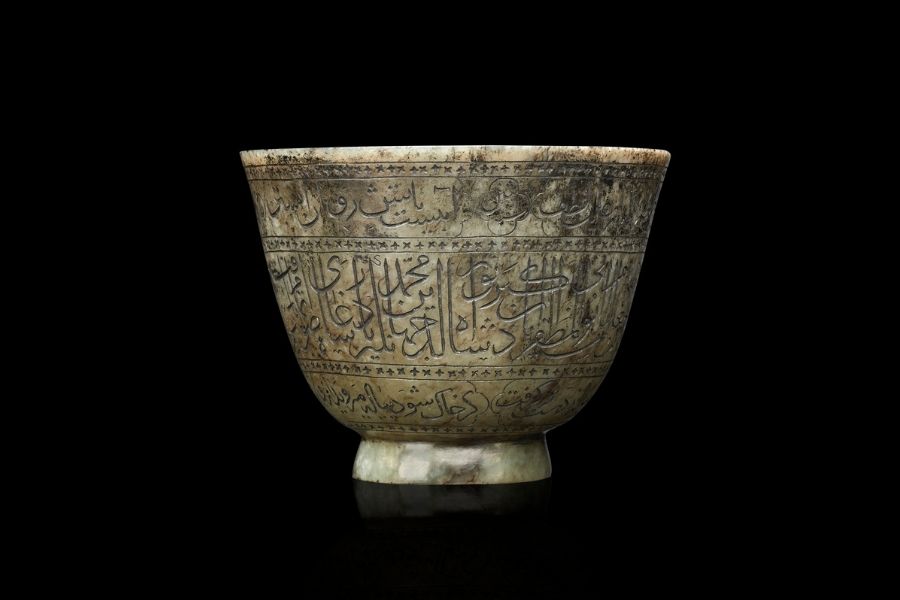

Two pieces in the lobby introduce us to the emperors’ stylishness and put faces to names. A triple portrait of Akbar handing his crown to Shah Jahan with Jahangir looking on, made by Bichitr in1630-33 during Shah Jahan’s rule, endorses Mughal lineage and legitimises their power. And a fine pale green jade wine tankard that spans the Mughal dynasty. Made for Timur’s grandson, Ulugh Beg (1394-1449), some 200 years later it was given to Jahangir and then inherited by his son, Shah Jahan: inscriptions record each owner. Meanwhile, a useful map shows the vast extent of the empire – and thus its taxable wealth – by Akbar’s death in 1605; it stretched from Kabul and the Safavid border to beyond today’s Bangladesh and well down into peninsula India.

A pale green jade wine tankard that spans the Mughal dynasty Victoria and Albert Museum/ The Al Thani Collection/Prudence Cuming Associates

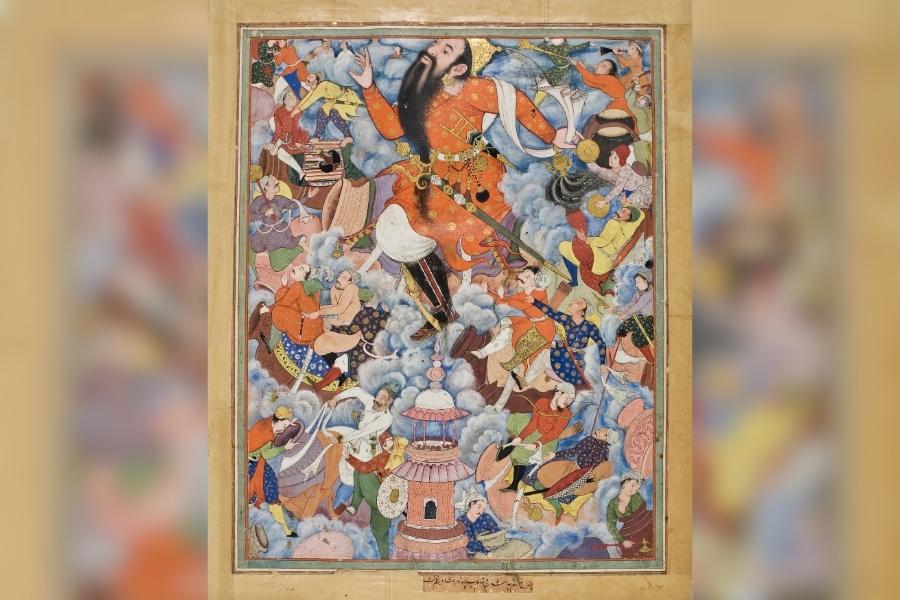

Plunging into the reign of Akbar (1556-1605), the show succeeds in the Himalayan job of conveying Akbar’s innovative policies across his newly won empire and how he used art to build cultural bridges, show tolerance and encourage Muslims to learn about Hindu cultures. Pages from the Akbar-Nama, his lavish official royal diary, show Fatehpur Sikri being built – the city he hoped would emulate Timur’s legendary Samarkand, which his grandfather Babur had thrice won and lost; here he built an imperial workshop and library. One of the three large folios displayed from the1,400-page Hamzanama, his first big manuscript project (1557-77), boldly depicts a hairy demon in delicate Safavid style gleefully abducting the sleeping king of Ceylon (Sri Lanka) on a strawberry-pink mountain. For fine calligraphy, the most respected Muslim art, there are four pages of handsome muhaqqaq script and ownership seals from a Quran – the subject of Sims-Williams’ essay. Akbar could not read, but he was an intense listener with a disciplined memory.

One of the three large folios displayed from the1,400-page Hamzanama, Akbar’s first big manuscript project (1557-77) Victoria and Albert Museum/MAK/Georg Mayer

A tender painting of Sita shying away from Hanuman, believing he is Ravana in disguise, comes from Akbar’s 1594 commission for a Persian translation of the Ramayana, part of Akbar’s efforts to make his international court of Turks, Persians, Rajputs and a variety of other Hindu communities more cohesive by learning about each other’s traditions. Here, too, is a copy of the remarkably frank diary of his hero grandfather, Babur, founder of the Mughal empire (said to be the best ruler’s diary until Queen Victoria’s), which Akbar had translated from Eastern Turki into Persian for all to read. For Persian won out over other language contenders thanks to Akbar’s finance minister, Raja Todar Mal, who overhauled the Mughal revenue system and persuaded his master to make Persian the official administrative language of the empire. A small but strong portrait acknowledges his importance.

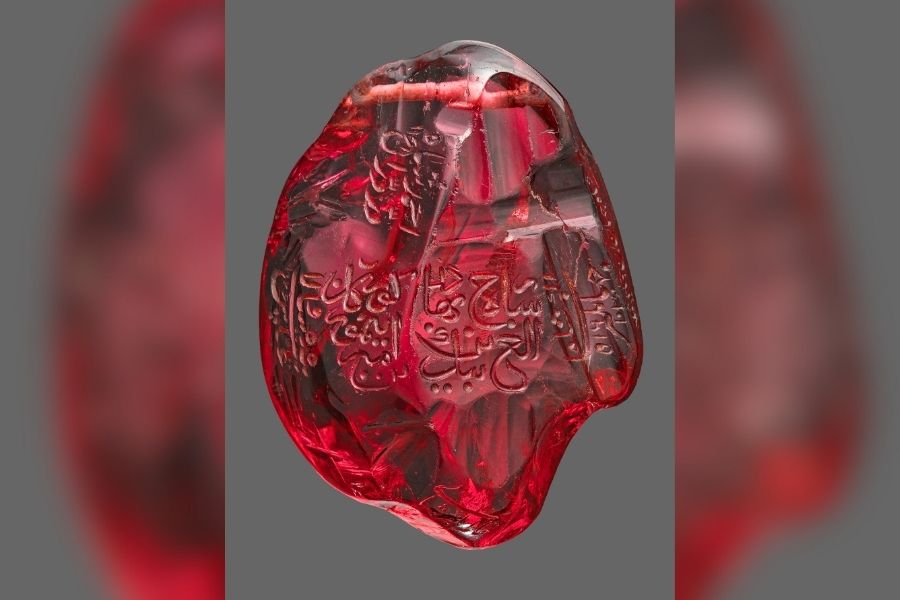

A raspberry-pink translucent spinel, once part of Shah Jahan’s dazzling, gem-encrusted new throne completed in time for Nowruz festival, 1635 Victoria and Albert Museum/al-Sabah Collection

Other crafts were developed to new heights under Akbar, too. A stunning carpet covered in frolicking cows, tigers and elephants, is already developing the distinctive Mughal boldness in design and colour, and is testimony to Akbar transforming the quality and quantity of carpet production in his empire, probably thanks to Central Asian experts. Akbar also picked up on existing fine craftsmanship. Having conquered Gujarat in 1573, his court commissioned high-quality objects from Ahmedabad, a hub of craft production. The pieces on display show off teak inlaid with ivory, and frames coated with patterns of mother-of-pearl which came from the shell of the green turban sea snail found locally in the Gulf of Kutch. Akbar’s curiosity led to him to receiving Jesuit priests (raising their false hopes of a royal conversion). After he put their gifts of European Christian images in his atelier, his artists promptly added flowing robes, angels and halos into the developing Mughal style – the V&A’s Portrait of a European in his big floppy hat reminds us that Europeans were collectively dismissed in India as ‘hat-wearing’ people, a pejorative that lasted into the British period.

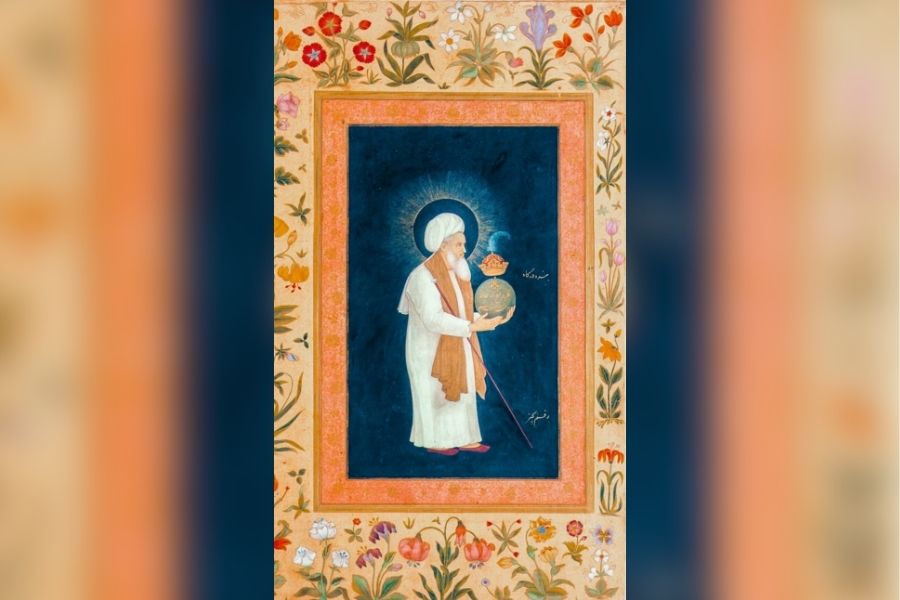

An imaginary portrait of Mu’in al-Din Chishti (1143-1236)

And that is just the Akbar section. Move onto those for Jahangir and Shah Jahan, when revenue flooded into royal coffers and court arts reached their peak of refinement, and each masterpiece deserves quiet contemplation. Here are two stunners. An imaginary portrait of Mu’in al-Din Chishti (1143-1236), founder of the Sufi order that spread rapidly thanks to royal patronage, was probably made when Jahangir’s court was at Ajmer from 1613 to 1616, and later laid down on its luscious flower border. Finally, a breathtaking raspberry-pink translucent spinel, once part of Shah Jahan’s dazzling, gem-encrusted new throne completed in time for Nowruz festival 1635. Given to Jahangir by Shah Abbas of Iran in 1621, its six inscriptions span ownerships by Ulugh Beg, whom we met in the show’s lobby, three Mughal emperors and Ahmad Shah Durrani, founder of modern Afghanistan. Today, it is in the Al-Sabah Collection in Kuwait.