|

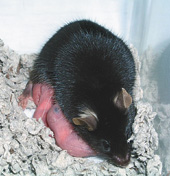

| The fatherless mouse, Kaguya, giving birth. (Reuters) |

In a genetic version of Heather Has Two Mommies, researchers have combined two unfertilised eggs to create a fully fatherless mouse.

The mouse, named Kaguya after a Japanese princess of legend, grew normally to adulthood and bore her own young. Researchers created her with a technique called parthenogenesis, or virgin birth, which occurs naturally in lower creatures from insects to snakes, but was long thought to be impossible in mammals.

The feat, to be reported in today’s issue of the journal Nature, should prompt no worry in men that they will soon become reproductively obsolete, researchers say, because the laboratory tricks used were complex, inefficient, and many years away from possible use in humans. But its success does add a new chapter in the proliferation of novel ways to reproduce, from in-vitro fertilisation to cloning.

“In principle, you can do without Dad for fertilisation,” said Kevin Eggan, a Harvard developmental biologist.

Heather Has Two Mommies is a well-known book, published in 1989, that describes a small girl with two lesbian mothers and promotes the acceptance of non-traditional families. Advances in mammal parthenogenesis could lead to ways to produce therapeutically useful human stem cells without destroying embryos that might otherwise have grown into human beings, some researchers say.

Scientifically, the experiment marks progress in understanding a key aspect of mammals’ sexual reproduction called genetic imprinting — a process in which certain genes in a fetus are turned off or on depending on whether they are inherited from the mother or the father.

Imprinting is believed to stem from an evolutionary battle between the sexes for the mother’s resources in the womb. In many mammals, offspring from different fathers may be competing in the same pregnancy, so it is in the interest of each father’s genes to programme the offspring to grow as big and strong as possible, the theory goes.

But mothers’ evolutionary interest lies in having as many babies as possible, so their genes try to programme offspring to be of more moderate size.

Scientists believe this competition is essential to the healthy development of a mammal, which explains why attempts at parthenogenesis in mammals — using chemicals or other means to coax an egg into dividing and growing without sperm — have never worked.

In the Nature report, a team led by Tomohiro Kono of Tokyo University of Agriculture combined eggs from two female mice, one normal and one a newborn in which two genes had been altered in an attempt to simulate the effect of a father’s imprinting.

The experiment, tried initially on 457 eggs, yielded eight live embryos, according to autopsies performed on host mothers. One, Kaguya, grew up and reproduced by mating in standard fashion. Kaguya and her siblings, which did not survive, had surprisingly normal gene activity, the researchers noted.

“It’s amazing that altering the expression of just two imprinted genes can have a ripple effect on the rest of the genome,” an accompanying commentary in Nature said.

The Nature paper does seem to prove that the only thing stopping mammals from reproducing through parthenogenesis is imprinting, said several biologists unconnected to the paper. But it raises more questions than it answers, they said, because it is so baffling that the researchers’ gene manipulation could have such a gigantic effect.

Apparently, even when an animal’s imprinting is radically altered, “there can be mechanisms in those extreme situations that can compensate” enough to allow for normal development,” said Eggan, the Harvard biologist.