|

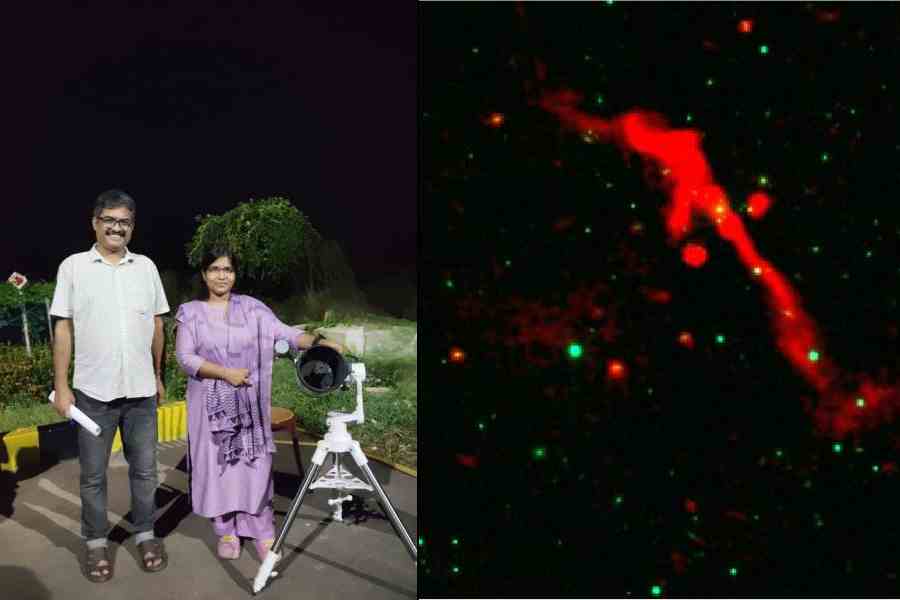

| Law and disorder: A protest against human rights violation in Kashmir provokes a reaction from the police |

News items such as these aren’t a rarity in today’s newspapers. Somewhere in the country, an assault victim approaches the police to file a first information report (FIR), only to find that the cops are in no mood to register one. Elsewhere, people may be kept in custody for months on the apprehension that they may commit a crime. And all too often, a person, arrested for an offence, is denied bail without any rhyme or reason, when the law states that he or she is entitled to bail.

It’s not just the system at which fingers can be pointed each time such incidents make headlines across the country. Public ignorance is also one reason citizens are often denied their civil and political rights. For it is only when you know your rights that are you in a position to demand them.

A new book, edited by the South Asia Human Rights Documentation Centre (SAHRDC), is a step in that direction. The Handbook of Human Rights and Criminal Justice in India: The System and Procedure, released in New Delhi last week, provides readers with an updated overview of complex legislation and explains the rules that the police and the judicial system have to follow while dealing with criminal cases. It attempts to familiarise readers with the criminal process to make it appear less daunting, apart from assisting them in recognising and asserting their rights.

The book, however, is not the first attempt at disseminating legal knowledge for the benefit of the common man. In the 1950s, a monthly, Civil Liberties Bulletin, was published at Pune with a similar aim, and was followed by many other journals of its kind. Of late, several educational institutions have begun extra-curricular courses dealing with legal issues for their students. Says Anil Wilson, principal of St Stephen’s College, Delhi, which introduced one such course last year, “It gives our students the confidence to stand up to the authorities and say, ‘I know the law as well as you do’.”

But most of these initiatives are or were limited to a niche audience for geographical or institutional reasons. “It is unfortunate that Indian civil liberties movements have always been episodic, and there has been little effort to ensure a constant review of the system,” says columnist and lawyer A.G. Noorani, referring to the work done by public forums such as the People’s Union for Civil Liberties and the National Human Rights Commission.

The ‘Handbook’, in that context, definitely has a greater reach, being published documentation. “It fills a gaping void in Indian legal literature. Nothing like it has appeared before,” notes Noorani in the foreword to the book.

But what, really, leads to the void that Noorani refers to? The book underlines the fact that criminal law in India is contained in a number of sources. When it comes to criminal procedures, the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC), along with other statutes, is exhaustive enough to cover most situations. But the complexity of legal legislation often leads to a situation when a particular law fails to adequately outline a certain topic. It is then that judges are free to rely on common law to arrive at what they interpret as the most just and applicable rules.

“Accountability is another topic that concerns us today,” says Ravi Nair, executive director of the New Delhi-based SAHRDC. “One often wonders how the system can be held accountable unless the shield of official immunity is removed.”

Nair’s words are indicative of the privileges that the authorities set apart for themselves, such as reservations within the CrPC that say official sanction needs to be obtained before a civil servant can be prosecuted. “Yet, another issue that needs urgent attention is that of police reforms, which is currently in an abysmal situation,” says Nair.

The book, through various sections such as criminal procedure and human rights, FIR, investigation, bail, detention and trials, seeks to address the problems and reservations that plague the system and prevent people from accessing their rights.

For example, though compensation for serving time in jail for an offence not committed is not mandatory in India, the book mentions the case of Rudal Sah, who was acquitted by a sessions court in Bihar on June 3, 1968, but was not released for 14 years. He petitioned the Supreme Court for compensation. The court stated: “The right to compensation is some palliative for the unlawful acts of instrumentalities which act in the name of public interest... Therefore, the State must repair the damage done by its officers to the petitioner’s rights.” It awarded him a compensation of Rs 35,000.

“An enlightened public is perhaps the first line of defence for civil liberties,” says Nair. And it is this very purpose that the book intends to serve. It’s only when you know your rights, the experts stress, that you will know when they are missing.