Think nautanki, and you think of Waheeda Rehman. Remember Teesri Kasam, that old Raj-Kapoor-Waheeda Rehman starrer that opened a chapter in the annals of Hindi cinema with its poignant tale of a bullock-cart driver and his love for a nautanki artiste? Remember her swirling around and singing, “Pan khaye saiyyan hamaro”?

It wasn’t always like that. In the early decades of the last century, nautanki stuck to a script and setting. Up on the stage, the princess sat in the upper window of a house while her dauntless lover serenaded her from below. The princess returned a high-pitched love song, as she twirled her lehanga, flashed her ankle bells and coyly covered her tomato-red cheeks.

Every one in the audience — watching from balconies and housetops and on the streets — knew those bright red cheeks belonged to a man. But no one really cared. That’s because north Indian folk theatre was strictly an all-male preserve. And rightly so, thought its torch-bearers. A nocturnal, high-decibel art form was no place for a woman to be. Till a perky, 12-year-old lower-caste peasant girl rewrote the rules of the game in 1932. Gulab Bai, India’s first woman nautanki artiste, became the best known name in the business, earned more than her male colleagues, started her own theatre company and won a Padmashree, considered the highest cultural icon of the elite.

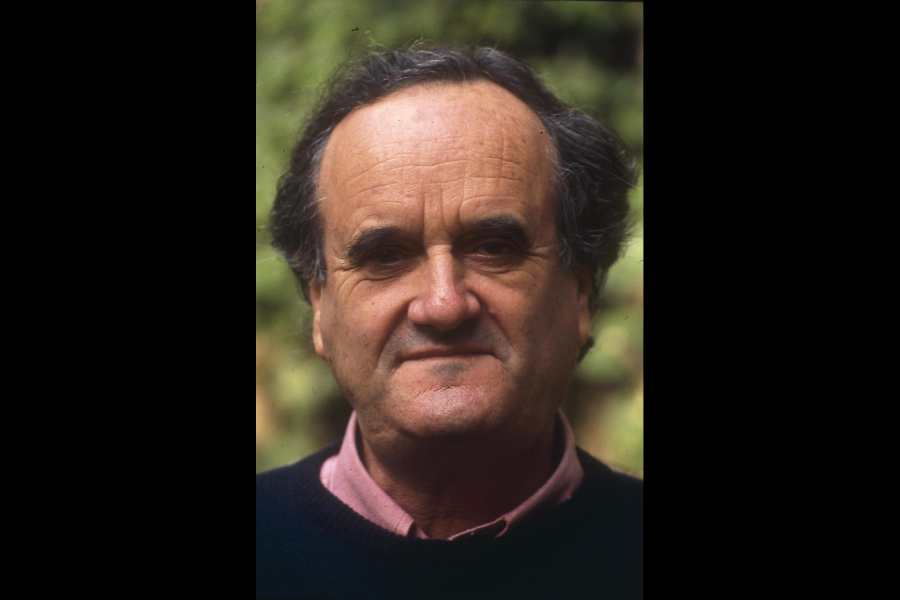

Seven years after her death, Penguin is publishing Gulab Bai’s first biography. Authored by Deepti Priya Mehrotra, the book is slated to hit the stands next year. It was her fascination for street theatre that led Mehrotra, a Delhi University lecturer, to Gulab Bai. While in college in Delhi in the early 1980s, Mehrotra and other like-minded women had used street theatre as an effective mode to spread awareness about issues such as rape and dowry. For Mehrotra — a product of your urban, free-thinking value system — it was hard to imagine that till half a century ago, women had no place in theatre. “Women had no voice in a powerful means of communication like theatre,” she rues. The dichotomy only enhanced her interest in Gulab Bai. And the germ of an idea of a book on the first woman of nautanki was sown.

Mehrotra, 42, has recreated Gulab Bai’s life story without ever having met the artiste. There aren’t even any photographs of Gulab Bai in her younger days. All that Mehrotra relied on were stories — about Gulab Bai’s ravishing beauty, powerful voice and steely determination to fight all odds.

What struck Mehrotra the most is the distinct Gulab Bai stamp that nautanki bears even today. “She made folk theatre a national art form. Something that no male artiste could manage,” she says. Gulab Bai came from a backward Beria caste family of Balpurva, in the Farukhabad district of Uttar Pradesh. The women folk in this caste sang, danced and earned a living for the family. Gulab Bai, the eldest of 10 siblings, joined this family business at the age of five. She was 10 when she saw her first nautanki, at a mela. “And she was hooked,” Gulab Bai’s daughter, Madhu, told Mehrotra. But there was no place for women in a nautanki, and troupe manager Tirmohan Ustad flatly turned her father down when he requested him to take his daughter in.

But Gulab Bai was not the one to give up either. She asked Tirmohan to hear her sing just once. “The story goes that Tirmohan was floored by the power in the young girl’s voice,” says Mehrotra. He agreed to hire her on a monthly wage of soap, oil and three square meals a day. Gulab Bai couldn’t have asked for more. The book maps the smooth ride to stardom for India’s first female nautanki artiste. By the time she turned 15, Gulab Bai had become a heroine. She was enacting all the plum roles — Laila in Laila Majnu, Shireen in Shireen Farhad and Taramati in Raja Harishchandra. Gulab Bai was a complete natural on stage and worked wonders for Tirmohan Ustad’s small-time troupe. The troupe would travel from town to town and set up camp at the site of local melas. They did not stay in any place for longer than a month. A kettle-drum would announce the start of the night-long nautanki. The actors had to be deep-throated enough to reach a thousand ears. Crowds flocked to his nautanki to watch a woman perform a woman’s role. “Gulab Bai was undoubtedly an excellent artiste. But her gender became her real USP,” says Mehrotra.

Other troupes began hiring women artistes to keep pace with Tirmohan’s success. The nautanki stage was no longer a male-dominated arena — though women on stage continued to be an anomaly in north India’s patriarchal, purdah-bound society. Gulab Bai failed to win social sanction for female nautanki artistes. “They became objects to be admired from a distance,” says Mehrotra. For women, control on sexuality and marriage was held as the biggest virtue of all. A woman stage artiste was considered unfit to marry. Gulab Bai herself had two failed relationships and four children out of wedlock.

On the one hand, women nautanki artistes were idolised. Crowds would gather to catch a glimpse of their home-grown heroines. Very often, men would fight to catch a female artiste’s attention. “Gulab Bai’s sister, Sukhbadan, remembers a man being knifed because she looked at him,” says Mehrotra. On the other hand, the artistes faced heavy social censure. “They were typecast as women with loose morals who bared their bodies in public,” says Mehrotra.

Still, professionally, nautanki gave lower-caste women a rare chance to earn money and clout. By the 1940s, Gulab Bai was earning a handsome salary of Rs 2,200 per month — several times more than the earnings of a district magistrate, went a popular comparison. In 1955, she set up her own theatre company, The Great Gulab Theatre Company, which hired 70 people. Her thumri and dadra recitals were recorded by HMV in the early 1960s. She won a series of awards and built a mansion for herself in Balpurva.

But the house that Mehrotra saw was the cramped two-room unit where Gulab Bai had lived with her sisters in Kanpur’s Railway Bazaar — a locality that housed all nautanki artistes “That house was the closest I got to getting a feel of my protagonist,” she says. To research her book, Mehrotra relied heavily for information on Gulab Bai’s family members — her three sisters and four children — and fellow-nautanki artistes. The tales about Gulab Bai, of course, were often blown up beyond proportions — which meant that Mehrotra had to cross-check and re-examine every bit of information.

The one issue that was never in doubt, however, was the decline of nautanki. Even though Gulab Bai fought hard for the cause of the theatre form, she could not save it from extinction. Starting from the 1970s, money, market and patronage for folk theatre declined.

This was the time when Bollywood was hogging the public mind-space. Nautanki began to mimic Bollywood to stay afloat and progressively declined in quality and form. Today, nautanki survives only as a commercial dance show at weddings and family functions.

Mehrotra’s book is a requiem to nautanki, and a toast to a woman who strode its world. It is the tale of a young artiste who single-handedly opened the curtains of folk theatre for women.