|

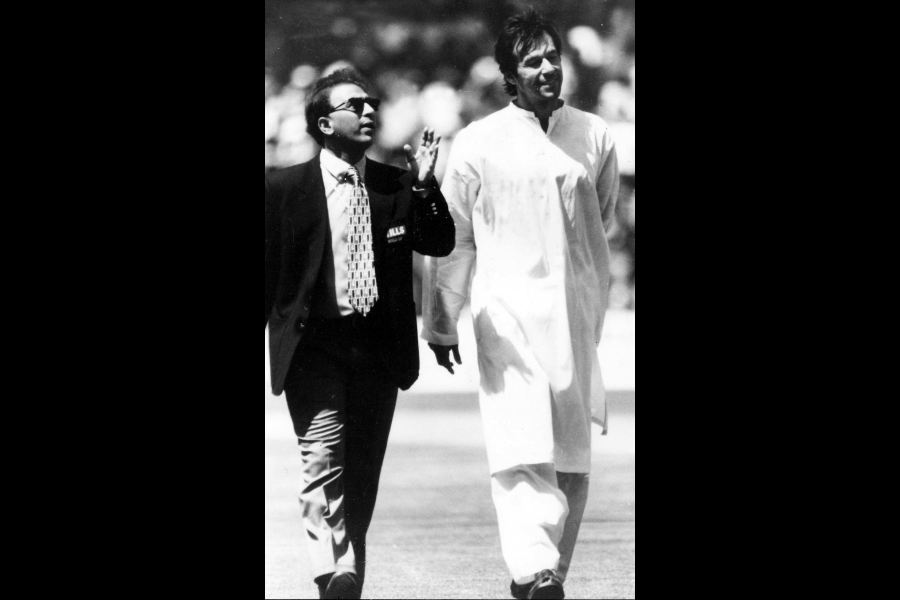

| Jazz veteran Benny Golson playing with John Betsch (drums) and Pierre-Yves Sorin (bass) at the Saint Louis jazz festival. (Reuters) |

Saint Louis (Senegal), May 24 (Reuters): Forget martinis, black polo-necks and cigar smoke. Think wild rhythms, gyrating dancers and virtuoso musicians wandering in off the dusty African streets to jam.

This is jazz as rarely seen in Europe or the US, spontaneous and unschooled. Raw local talent rubbing shoulders with musicians at the top of their careers, and no club owners demanding smooth, sanitised performances for suited clientele.

Africa, say musicians at the continent’s biggest jazz festival, is where jazz is living its second youth, and Saint Louis, a town of faded colonial villas straddling an island and the mainland in northern Senegal, wants to be its centre.

Big names play to paying audiences on the main stage during the town’s annual festival while Afro-beat rhythms bounce off the buildings around the main square.

The hottest action is after hours in the bars, where professionals from abroad form impromptu groups with the locals.

“In Europe, jazz has got a little closer to classical music, a little more academic. Now there’s a return to Africa,” said Parisian drummer Frederic Delestre, taking a break from a jam session to talk rhythm with a local teenager.

A saxophonist slumped in an armchair at the back of the bar is suddenly inspired by a singer and reels off a riff. Across the steamy room a teenager bangs out a rhythm on a table with his drum sticks.

“People are looking for the kind of authenticity you find here. You can tell these guys haven’t worked with metronomes, that they’ve learned totally empirically,” said Delestre.

Many of Senegal’s musicians consider themselves griots — story tellers who recount legends using music and dance and have learned centuries-old rhythms on djembe, sabar and tama drums from their parents and grandparents.

Below wooden balconies and wrought-iron rails in the back streets of the town, France’s first settlement in Africa, music drifts out from open windows — the sound of a drum or a woman singing as she works.

“When you’re a baby and you’re in your mother’s bed you hear music. Your mother sings when she puts you on her back. It’s in the blood,” said Ibnou ’diaye, singer and guitarist with local folk group Ndiol’or.

“When we hear thunder, instead of being afraid, we try to work out what the rhythm is.”

Jazz is said to have been born in the US when European instruments met African rhythms and musicians started using techniques employed in slave music, like slurred notes, call and response, and wild falsetto cries.

From its conception, improvised interaction between players has been one of its cornerstones — some US states even banned drums in the 18th century fearing Africans would develop a system of communication and organise a rebellion.

“Directly or indirectly Africa taught the world what rhythm is. It’s everywhere here. They’re just born like that,” said Jean-Loup Longnon, a trumpeter, singer and pianist from Paris.