|

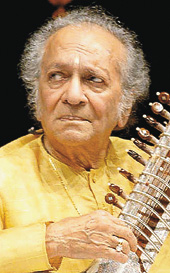

| Ravi Shankar: Still practising hard |

West Palm Beach (Florida), April 15: Near the end of a free-wheeling conversation with Ravi Shankar, the man who almost single-handedly introduced the world to Indian music, the humble virtuoso pauses to make a point.

?Yesterday was my 85th birthday,? he says in a rare display of pride, speaking on phone from his California office.

It?s a point made with acknowledgment of all he?s accomplished in those 85 years, from his work with the late Beatle George Harrison, who proclaimed him ?the Godfather of world music,? to his non-stop touring. But it?s also perhaps a way of admitting the challenges he faces: Shankar knows he?s playing on borrowed time ? ?The hand ... with age, it becomes stiff,? he says ? but he?s eager to fight the good fight.

A master, in other words, never rests. And that?s what Shankar really is. Not just an instrumentalist. Not just a composer. But a master ? one who has not only attained the highest level of achievement, but who also devotes his time to training and mentoring his disciples.

Among those who have studied or partnered with Shankar are such greats as Harrison and the composer Philip Glass and such promising newcomers as his 21-year-old daughter, Anoushka.

Before the serene-faced musician, who plays the sitar, became established worldwide, the Indian classical tradition was largely unknown in the West. It took Shankar to bring its strange, exotic beauties ? the melodies and rhythms that strike a profoundly mystical note, the performers who improvise in a manner that puts even many jazz greats to shame ? to the West?s attention.

In the process, he became a well-known figure in the counterculture movement of the ?60s ? he even played at the ultimate hippie gathering, Woodstock. But Shankar?s work has gone far beyond that.

He has found ways to bridge musical landscapes, writing two concertos for sitar and Western-style orchestra, plus music for the late flutist Jean-Pierre Rampal and late violinist Yehudi Menuhin. He has composed for films and dance companies. He has won Grammy Awards, been honoured with doctoral degrees and even was reportedly nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Oh, and one more thing: He?s the father of pop vocalist Norah Jones.

Shankar stresses that Indian music, which is rooted in a system of ragas, was never an easy sell with Western audiences. The listeners ?came in the beginning with a very flippant attitude, just like going to a pop concert,? he recalls.

At the same time, Shankar clearly welcomed the attention the music was suddenly receiving. But as much as he?d like to take credit for it, he defers to Harrison. ?He was the person who really opened the gates,? Shankar says.

Shankar adds that he ?didn?t know much about the Beatles? when Harrison first approached him in the mid ?60s, but was impressed by his desire to learn. ?He was again and again asking me about the spiritual quality of our music. ... He got so much into it, he started writing songs about those ideals, which was very interesting.?

Harrison, in turn, credited Shankar with changing his perceptions, musical and otherwise. ?Ravi plugged me into the whole of reality,? he said in 1999.

Harrison also recognised that Shankar not only opened Western ears to Indian music, but, by association, to all kinds of non-Western music. But these days, Shankar considers the title of ?Godfather of world music? a mixed blessing, since much of the ?world? genre is now rooted in slick commercial fare that blends pop with ethnic influences.

?The good side is that everyone is much richer in being able to hear different types of music,? Shankar says. ?But it?s becoming (left to) half-baked musicians. ... This whole fusion thing is not very interesting.?

Shankar?s career, of course, predates his involvement with Harrison. He first became interested in performing as a youngster when he travelled to Europe and joined his brother Uday, a professional dancer who was introducing Indian culture to the West. ?I grew up mostly with music, dance and the stage. It was like an adult life,? he recalls.

But to become a truly successful performer himself, Shankar had to return to India, spending several years learning and, yes, mastering the sitar. As he once explained, ?It takes many years to be bound by rules (to) be free as a bird.?

Over the years, Shankar has passed that lesson on to many students. But these days, he?s particularly focusing on his daughter, Anoushka. He admits it?s a little different from the usual guru/disciple relationship. ?I had to pamper her when she was little,? he says. But now, he notes, ?She?s so extremely talented, it?s a pleasure teaching her.?

And what about his other daughter, Norah Jones?

Shankar wasn?t actively involved in raising her ? her mother was from another relationship of his. But he?s grown to know her in recent years. ?We?re very close again. I?m so proud of her. ... Her music has such a pure beauty,? he says.

One could say that Shankar?s two daughters are part of his growing legacy ? as a man and musician.

But Shankar would rarely put it that way. If anything, he?s hesitant to see himself as a legend. At 85, there?s still work to be done ? and that includes his daily practice routine. ?It needs such tremendous concentration and training,? he concludes of his craft. ?Unless I practice, the flow becomes a little muddled.?