|

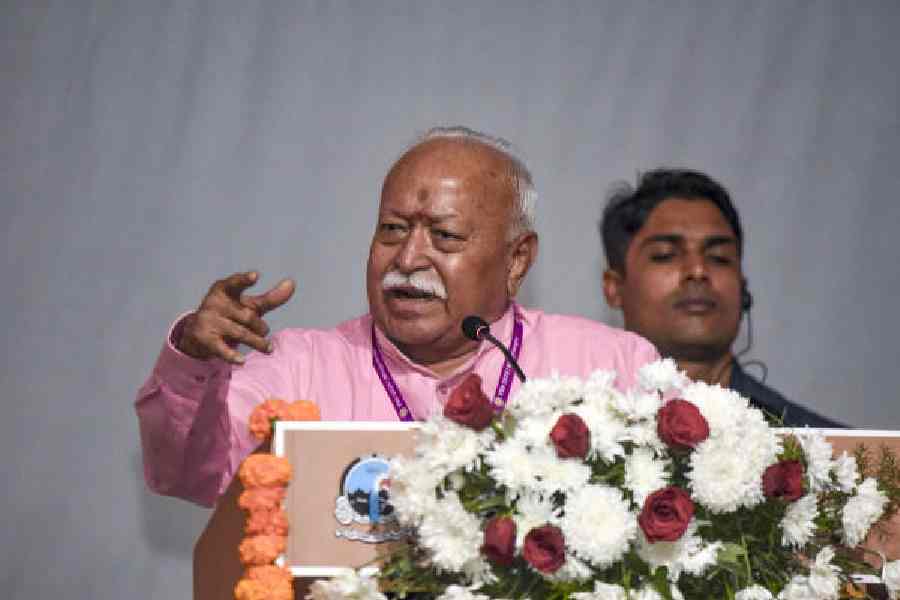

| Picking up the pieces: Dhananjoy’s widow Purnima is trying to get her dowry back from her in-laws, and (below) a file picture of Dhananjoy |

|

If they hang him, we will kill ourselves.” So said Bangshidhar Chatterjee, on behalf of his family, days before his son, Dhananjoy Chatterjee, was hanged to death at the crack of dawn on August 14, 2004, for the rape and murder of a schoolgirl, who lived in the building where he worked as a watchman.

“I want my husband to come back so that we could start life all over again and have children.” So said Purnima Chatterjee, his wife. “If they hang him, I’ll go crazy.”

One year later...

In the remote and picturesque village of Jamdoba ? a couple of hours’ drive from the town of Bankura, West Bengal ? little seems to have changed outwardly. There’s that same yellow mud hut by the same blue pond, where Purnima lives with her parents and where on a moonlit night a year ago, she spoke these words. There’s that same wooden door, painted the same gloomy green.

But inside, a lot has changed.

“If you’re looking for my daughter, she’s gone mad,” hisses Purnima’s mother, through the afternoon silence. And she has indeed gone mad? but only figuratively. As her mother says, “She’s going mad trying to retrieve her dowry jewellery from her in-laws and none of you is of any help.”

This perhaps is the biggest change that members of Dhananjoy’s family have undergone in the past one year. Their focus has shifted ? from trying desperately to save Dhananjoy from being hanged to trying to hang on to and get on with their respective lives.

According to psychiatrists, this is only natural. “For family members, the impending death of another member becomes psychologically traumatic,” explains consultant psychiatrist, Dr Debashis Ray. “The stress build-up during the period of uncertainty makes them long for release subconsciously. Often, after a long period of struggle, death brings a sort of closure, and ironically, a sense of relief.”

Physicians point out that when a terminally ill patient dies after a prolonged illness, family members react similarly. “They feel a sense of relief that the person is no longer suffering. They also feel freed from the mental trauma, physical stress, and, very often, the economic burden that they experience during the period of illness,” says Sudipto Goswami, CEO, Genesis Hospital, Calcutta, who regularly comes into contact with families of terminally ill patients.

For over 14 years ? from the time that he was arrested, tried, convicted and subsequently sentenced, to the day he was hanged ? Dhananjoy’s family members had struggled to try and cope with the crisis in their lives. They ran from pillar to post, and even petitioned the President of India for a pardon. They sold their property to garner funds for the trial. They lived in constant fear and uncertainty. And finally, they had lived on hope ? longing for a miracle that would save Dhananjoy from the noose.

When he was hanged, that hope was extinguished, but so was the agony of uncertainty.

“At least now he is not rotting in jail anymore,” Bangshidhar Chatterjee blurts out, sitting on a cot in the courtyard of their home in the village Kuludhi, an hour’s drive from Jamdoba. Then he adds quickly, “But my son’s hanging has killed me.” No, Bangshidhar doesn’t have to kill himself anymore. He insists he is “a living corpse”.

The macabre reality of his son’s hanging no doubt haunts him at unexpected moments. But his tears seem a little forced now.

The rest of Dhananjoy’s family too is moving on. There have been two marriages in the family since the hanging ? Dhananjoy’s sister has got married and so has Purnima’s younger sister.

“Why shouldn’t my sister find a groom?” asks Purnima’s brother, Falguni Mukherjee. “Our family hasn’t done anything wrong.”

Dhananjoy’s younger brother, Bikash, who works at a bicycle repairing shop and who bears an uncanny resemblance to Dhananjoy, hasn’t been able to find a bride, though. “No, I’m not worried about that,” he says, but he looks a bit troubled.

Dhananjoy’s family does not deny that Purnima “brought in a good dowry ? gold ornaments among other things”. But they insist that these had to be sold off during the trial. Says Bangshidhar, “Now they want it back. Where will we get it? Is this the way to act? She hasn’t even bothered to find out how we are.”

Dhananjoy’s family points out that the government has given her a job at the social welfare ministry’s Integrated Child Development Service Centre (ICDSC). “She gets a lot of money,” they say.

“She only gets a monthly stipend of Rs 400 per month,” counters Purnima’s brother. Purnima, herself, is quiet.

“She is always very quiet,” confirms Fakir Deoghuria, Child Development Officer at ICDSC, who informs you that she gets a salary of Rs 1,200 per month. He feels that she is coming out of the trauma slowly. After all, she was not really that unused to not having her husband around. They were barely married for a year before Dhananjoy was arrested and that too, he used to live mostly in Calcutta.

When asked if she would ever remarry, Purnima shakes her head. Her father explains, “Such things are unheard of here. You only get married once.”

So, a year after Dhananjoy’s death, life goes on for his family members. Not as usual perhaps, but the best that they can make of it.