|

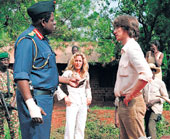

| Not so Ideal: A scene from The Last King of Scotland |

In the recent movie The Last King of Scotland, a freshly minted medical doctor, newly arrived in Uganda in 1971, becomes caught up in the population’s adulation of its new leader.

Seduced by the ruler’s larger-than-life persona — and his promise to allow the young man to help create a new health system for the country — the fictional Scotsman, Dr Nicholas Garrigan, becomes the leader’s personal physician and an adviser. The audience, however, knows that the boss, Idi Amin, will eventually be revealed as a brutal dictator. And as they say, it all ends badly.

But the movie simply depicts an extreme version of a not uncommon work-related misstep. In the real world, the problem begins when an employee views a prospective boss through rose-coloured glasses. When the infatuated new hire discovers the idealised employer’s true nature — the one not generally presented to the public — disillusionment sets in.

“The absolute heart of the novel is this idea of idealisation,” said Giles Foden, the author of the book of the same name that was the basis for the film. Foden described the doctor as craving excitement and being naturally drawn to Amin.

Unfortunately for Garrigan, Foden explained, the closer an underling is to a superior, the more likely he is to see flaws. Still, he said, “The subordinate partner deliberately stays somewhere he rationally knows is bad for him.”

It becomes, he says, like a self-destructive addictive habit. “When people bind themselves to someone in power, they’re free of moral responsibility in their own minds,” Foden said. “It takes something very dramatic to break the link.”

If breaking the link takes conscious effort, creating that link is considerably more subtle. “All of us, when we look for work, are projecting experiences from our past,” said Thomas A. Caffrey, a forensic psychologist in private practice in New York. “If someone is craving a father figure, they will be drawn more readily to a charismatic kind of leader.”

Toward the end of the film, Amin tells the doctor, who has belatedly become aware of Amin’s true colours, “You have grossly offended your father.”

Often, Caffrey said, the subordinate believes that the boss he so admires will pave the way to success and will even regard the employee as a family member.

Such yearnings come at a price, however, said Steven Berglas, a psychologist in Pacific Palisades, California. “Idealisation leads to devaluation,” he said, noting that the higher the pedestal someone is placed on, the greater the disappointment if they fall. ”

But even when the subordinate realises that the manager he once idealised does not measure up, he often still sticks around. “When an intelligent person makes a commitment to the course of action, he doesn’t back out,” said Berglas, the author of Reclaiming the Fire: How Successful People Overcome Burnout (Random House, 2001). “They think, ‘I’m bright, I can overcome the obstacles.’ So they escalate their commitment.”

George Kohlrieser, a psychologist and consultant who teaches leadership and organisational behaviour at the International Institute for Management Development in Lausanne, Switzerland, says these idealists stay because they are psychological hostages. “You become a hostage the moment you need to make a different choice and you don’t,” he said.

Kohlrieser, the author of Hostage at the Table: How Leaders Can Overcome Conflict, Influence Others and Raise Performance (Jossey-Bass, 2006), recognises the difficulty of leaving. Usually, he said, an employee quits working for a person whose values do not align with his own only when the pain of staying is too great to endure. Mourning is not atypical. Admitting to having made a bad choice “is a grief reaction”.

Once you realise the person responsible for your paycheck differs greatly from the person you once idealised, you need to ask yourself some tough questions, said Gayle Lantz, an executive coach and the owner of WorkMatters, an organisational development consultancy in Birmingham, Alabama.

“Typically, the people who are in those situations and realise there’s a disconnect end up leaving,” she said. “They are not willing to sacrifice their personal values.” Sacrificing the job instead, she said, is worth it to them.

Sticking it out has its own set of challenges. “People attempt to do that in the short term, but in the long run, they know it eats them up inside,” Lantz said. “That’s when they grapple with the other options they can explore.”

Organisations and corporations could conceivably alter the kind of culture that encourages misplaced reverence, but many companies prize charisma as a leadership attribute.

“Companies don’t want to stop it,” said Donna Flagg, owner of the Krysalis Group, a human resource and management consulting firm in New York. “Either these companies don’t understand it themselves or, in their opinion, it is serving the interest of the company.”

A highly idolised manager or chief executive is a magnet for publicity and media opportunities, even if the manager does not live up to the hype and many in the company know it.

“Companies don’t see the cost this has on the organisation,” Flagg said. “There’s the backlash to how people feel about that person. And then there’s distress, resentment, dissension and embitterment.”

Caffrey says that this type of letdown can leave a person “utterly bereft,” and the depth of the betrayal injury depends on an individual’s makeup. Those who strongly believe in themselves, he says, have an easier time of it.

“They’d say, ‘Too bad this guy is not what I thought he was, and I guess I have to work somewhere else’,” Caffrey said. “They don’t take it as personally.”

For others, however, severing ties with a person once perceived as grander, smarter, worthier and more visionary than oneself is a tough challenge. “Once people form an attachment, they find it hard to break,” Kohlrieser, the psychologist in Switzerland, said. “There is grief, even in breaking a negative bond.”