Pay a fine of Rs 100 or spend a month in prison for contempt of court. The convict refused to pay and was packed off to prison.

The scene unfolded not in 2020 but 61 years ago, in 1959, in a courtroom of Kerala High Court.

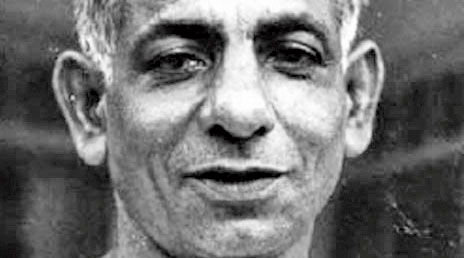

In the dock was not lawyer Prashant Bhushan — the fate of whose contempt conviction is expected to be known this week in the highest court of the land — but Mathai Manjooran, an editor and freedom fighter.

Six decades ago, Manjooran chose prison over apology in the contempt of court case, standing up for freedom of the press.

Manjooran’s Malayalam daily Kerala Prakasham had published a report dated July 29, 1958, about the death of six Congress workers from stab wounds after a clash with the then ruling communists in Varandarapally, Thrissur.

It appears that the report touched on issues that were sub judice, and this led to a contempt case against Manjooran and his printer and publisher Sudhakaran. Both denied the charge in their counter-affidavits.

They also refused to apologise, following which the case went ahead.

A year later, a 20-page judgement convicted Manjooran and Sudhakaran. Probably reluctant to send the editor to jail, the court offered him a way out. Manjooran was asked to pay a fine of Rs 100 or spend a month in prison. The punishment for his publisher was Rs 50 or 15 days.

Both refused to pay the fine and were sent to Viyyur jail in Thrissur to serve their terms.

Did the punishment serve its purpose? It doesn’t appear so from the reception Manjooran received when he was freed.

His friends and supporters organised a well-attended felicitation at Swaraj Round, a 2km roundabout in the heart of Thrissur and around 4km from the jail.

“They later took him for similar events in Manjooran’s (home district) Ernakulam and Kottayam, where he gave fiery speeches against the administration,” said A. Jayasankar, a lawyer who appears on television channels in Kerala as a commentator.

Jayasankar had done a video commentary on Manjooran when the Bhushan case was taken up by the Supreme Court.

“Manjooran was the then Prashant Bhushan,” Jayashankar told The Telegraph. “Manjooran told the court he was not ready to apologise for the report since he believed in freedom of the press.”

On Thursday, Bhushan had reluctantly accepted the apex court’s offer of a few days to consider tendering an apology for his tweets that had invited his contempt conviction. Bhushan, who has time till Monday, had on Thursday indicated he might not apologise.

Manjooran’s 50th death anniversary fell early this year, on January 14. It went largely unnoticed, possibly because he was a bachelor and there is no one to promote his legacy.

Jayasankar’s book Communist Bharanavum Vimochana Samaravum (Communist Rule and the Liberation Struggle) refers to the 1912-born Manjooran’s life as a freedom fighter, firebrand orator and socialist revolutionary.

Manjooran was just 15 when he took part in the protests against the Simon Commission in 1928. The book adds: “Mathai Manjooran was a firebrand who took part in the 1942 Quit India movement. He was the mastermind behind (the revolutionaries) ferrying explosives from Mysore and making bombs in Kozhikode.”

He later floated a party, the Kerala Socialist Party, a founding member of which became a judge in Kerala High Court. Although Manjooran was a critic of the communists, the second Left government of E.M.S. Namboodiripad made him labour minister from 1967 to 1969.

Some reports credit Manjooran with something that should strike a chord in Bengal. As labour minister, he was an ardent advocate of the gherao as a right of workers.