Only her death can prove she is living.

At 45, Gulabi Devi is a shrivelled, prematurely-balding woman, who has wasted her youth trying to prove she is alive. After her husband died, her relatives had a death certificate issued in her name and grabbed her property.

After decades of a futile fight that ravaged her youth, Gulabi, her frame racked by hunger and deprivation, looks at real death as deliverance.

Pushed out of her two-storied house in Devaria 15 years ago, Bhagyashrini Devi lives in a dark hole surrounded by four crumbling walls.

Like Gulabi, she was pronounced 'dead' after her husband's death.

In every part of Uttar Pradesh, there are 'dead' people trying to just prove they are alive.

After her husband Fakir Khuswaha's death in March 1980, 14 men barged into Bhagyashrini's house in Chipiyan village and threw her out. They were armed with a 'certificate' from the revenue department which proclaimed her to be 'dead' two years ago. They distributed the property left by her issueless husband among themselves.

It is the same story in village after village where people are declared dead by the revenue department, in collusion with members of the victim's family.

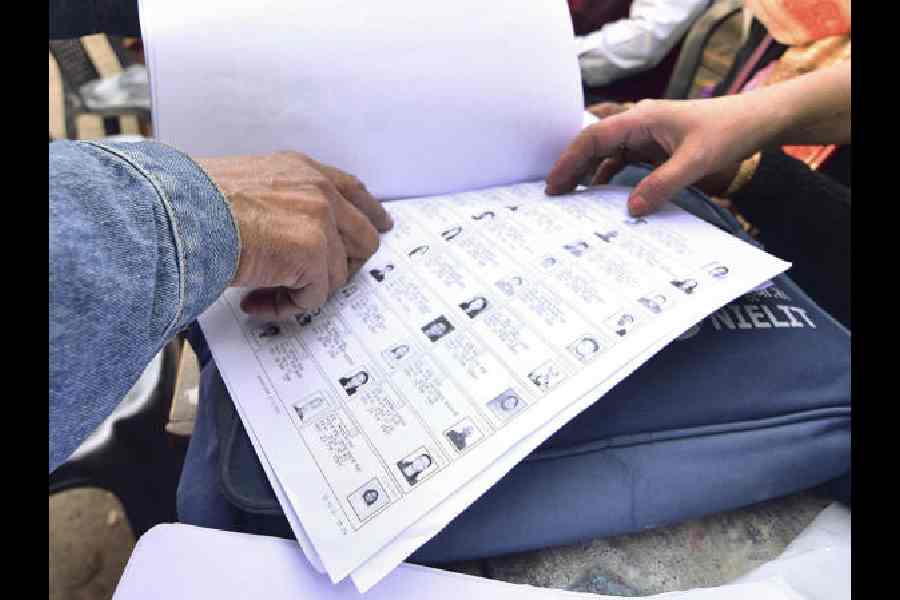

A tour of around 15 villages in Azamgarh, Varanasi and Gonda revealed that there are more then 1,000 such people.

The state government had directed the Revenue Board in October 1999 to launch an abhiyan (mission) to trace out Uttar Pradesh's 'living dead' and bring them 'back' to life. But the resurrection project has not been much of a success.

After it came to light that in Jaithpur village of Gonda district, 22 people were declared dead in May 1998 in one single day, the National Human Rights Commission rapped the state government and asked it to furnish a report about the 'deaths' within 10 days.

In January, Allahabad High Court had ruled 'to declare living people dead is a gross violation of human rights under Article 21' and referred the issue 'unanimously' to the rights panel.

The Association of the Dead has taken up the dead men and women's cause.

Its president, Lal Bihari, who suffixes 'Mritak' to his name, could successfully bring himself 'back' to life. He was declared dead in 1976, but pronounced living after 16 years.

But the struggle was 'killing'. He tried to contest the elections against Rajiv Gandhi for Amethi in 1989, which the high court said 'doesn't make sense' and his candidature was cancelled. He kidnapped his nephew and held him in captivity for 15 days so that a case against him would be lodged in the police station. The police laughed it off.

Then he created a ruckus in the Assembly and threw things at the Speaker. Though the police arrested him, they could not slap a case against a 'dead man'.

In 1994, he was pronounced 'living' again by the court.

Though the Association of Dead People has been fighting for its kind, they lack the funds. 'The lawyers charge exorbitant amounts to fight our cases,' says an association member.

In the Gonda village, while no one got the property back, 12 were 'brought back to life' after the government cancelled their death certificates. But four of those who were decrepit with old age and disease have died since then.

Says Gopal Bindeshwari, 70, 'After transferring my land to my four nephews I was declared dead. I fought for sometime and went to the police and hired lawyers. But now I feel defeated. Where do I get the money to feed the police and lawyers? Old people like me can only hope for death.'

In Mazharat, another village, Daya Ram Sangam, 'killed' by his own sons, says he has been fighting for 17 years and has lost the will to fight. 'I have no money, no strength. My own sons have declared me dead. I cannot fight anymore.'

Rajiv Sharma, chief revenue officer in Gonda, says it is very difficult to prove one is not dead after the revenue department says so officially. 'If the whole village says you are dead, what can you do?'

Police officials investigating such cases go and meet family members of the victims and say that the person in question is dead and gone.

'They produce witnesses who claim they have attended the funeral,' says Sharma, adding that 22 revenue officials have already been punished for forging documents. 'There is very little the old and poor can do,' he adds.

When Jaiprasad Tiwari of Gonda returned from Ahmedabad to attend his wife's funeral in his village, he found out to his surprise that he too had 'died' along with his wife in an accident.

His brothers, who had by then received a letter transferring the land in their names, called out some villagers who accused Tiwari of being an imposter and swore that the 'original' Jaiprasad had been cremated along with his wife.

'The police and revenue officials take money from both sides - those that want to prove others dead and those who want to come back to life,' says Brij Bhusan Khuswaha of Belloriganj.

'After a certain while it is better to remain dead,' he says, tears welling up in his weary eyes.

Wednesday, 11 February 2026

Wednesday, 11 February 2026