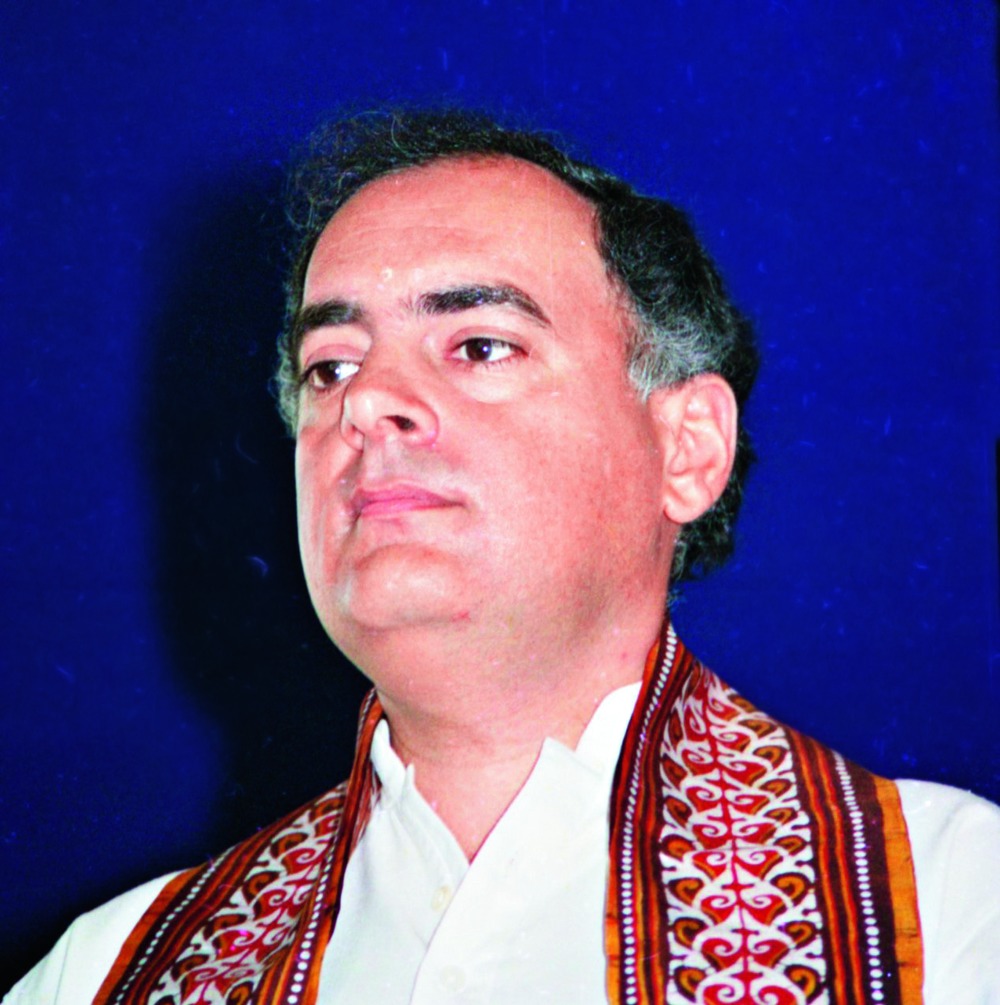

Aug. 16: Journalist Neena Gopal, who interviewed Rajiv Gandhi moments before he was assassinated in 1991, says the former Prime Minister had a premonition of his death.

In her book The Assassination of Rajiv Gandhi (Penguin), released yesterday, Gopal, who was foreign editor of The Gulf News then, recalls asking Rajiv whether he felt his life was at risk.

"Rajiv responded with a counter-question: 'Have you noticed how every time any South Asian leader of any import rises to a position of power or is about to achieve something for himself or his country, he is cut down, attacked, killed... look at Mrs (Indira) Gandhi, Sheikh Mujib, look at Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, at Zia-ul-Haq, (Solomon) Bandaranaike...'"

Gopal says that within minutes of making that prophetic statement that hinted there were dark forces at work and that he knew he was a target, Rajiv himself was gone. "It catapulted me from an unknown reporter to someone who would always be known as the last journalist to have interviewed Rajiv Gandhi, minutes before he died. A macabre twist. And not the kind of exclusive I had bargained for," she writes.

When Rajiv stepped out of the front seat of a car at Sriperumbudur, he had asked Gopal: "Come, come, follow me."

In response, she had told him: "I have one more question, I'll wait for you here."

When an LTTE suicide bomber blew herself up, killing Rajiv instantly, Gopal was barely 10 steps behind. "...But as the huge explosion went off a few minutes later and I, standing about ten steps away, felt what I later realised was blood and gore from the victims splatter all over my arms and my white sari, a nameless dread took hold - something terrible had happened to the man I had just been talking with," Gopal recalls.

In her book, Gopal quotes Chandran Chandrasekharan, a senior Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) officer, telling her: "We failed Rajiv Gandhi, we failed to save his life."

The author insists there were hundreds of intercepts between April 1990 and May 1991 that showed that the LTTE was planning to kill Rajiv. She quotes Col Hariharan, who had a small army of anti-LTTE Jaffna Tamils keeping an eye on the militant group for him, as saying that he was taken aback when he was given a cassette to listen to.

Hariharan's code-breakers who had decoded the intercepts, in a mix of Tamil and English, told him a plot was afoot to kill Rajiv. "Blow Rajiv Gandhi's head off", "Eliminate him", and "Kill him" were some of the intercepted messages in English.

Gopal says that of the hundreds of intercepts between the 38-odd Tamil insurgent camps in the Nilgiris in India and their cohorts in Jaffna, Sri Lanka, almost every single one centred on arms shipments and gunrunning between Vedaranyam and Point Pedro, barely 18km from the coast to coast.

"But no intercept would be as chilling as the kill order that came through in short bursts of VHS communication on a frequency that the LTTE favoured, that April day in 1990," Gopal says.

While researching for her book, Gopal had interacted with Chandrasekharan, who had served as an additional secretary in the cabinet secretariat and was in charge of the RAW in Sri Lanka.

Chandrasekharan, now 85, had been sidelined once the Rajiv government fell in 1989 and his years of cultivating the Tamil militants came to nought.

"By that time, the government had changed. Nobody wanted to hear what we had to say anyway. And I had been shunted out," Chandrasekharan told Gopal. "The IB and RAW didn't agree on much. If we had read the signals right, if we understood what was going on in (LTTE chief) Prabhakaran's mind, who knows, we could have prevented this. It was our fault, we made a huge error of judgement. We misread Prabhakaran. We never believed he would turn against us in this manner. We should have seen it coming. We didn't. We failed Rajiv Gandhi, we failed to save his life," he said, close to tears as he spoke to Gopal.

The author says the V.P. Singh government and subsequently the Chandrashekhar government remained casual towards security requirements for Rajiv.

"They failed to restore the 'Z' security that Rajiv Gandhi used to have before he lost the prime ministership. Opposition leader or not, he was on the hit list of the Khalistanis and the Sikhs, and warranted more than the negligible cover he had been provided," Gopal writes.

In his assessment, Rajiv was too proud to ask for security from his political opponents who lacked the generosity of spirit to give it to him.

"In fact, Col Hariharan said he had his knuckles rapped for raising the alarm about the plot to assassinate the former prime minister even though the intercept was nothing less than Prabhakaran putting a hit on Rajiv Gandhi."

Hariharan told Gopal: "I was asked to stick to my brief. The IPKF (peacekeeping force) was after all, packing up to leave Sri Lanka, removing the main source of the grouse against Rajiv Gandhi."

Politically too, Hariharan felt, he and other army personnel had become unwanted baggage in both Colombo and New Delhi. Their "mandate was finished", he told the author, "we were on our way out. "But R&AW, overconfident of its influence over the LTTE, failed to factor in that revenge was always on the cards when it came to VP (Vellupillai Prabhakaran)."

Gopal today received a call from Priyanka Gandhi's office. The caller said Rajiv's daughter wanted to meet her.