New Delhi, March 23: Narendra Modi sent junior foreign minister V.K. Singh to Pakistan's mission here this evening to maintain a longstanding tradition, but serial flip-flops amid a maelstrom of studio protests exposed the government's dilemma on ties with a country Modi relished baiting a year ago.

Singh spent barely 15 minutes on the lawns of the Pakistani high commission, where the neighbouring country was celebrating Pakistan Day. But his brief to drive down to Chanakyapuri capped three days of twists and turns in the Modi government's response to Kashmiri separatists joining the event.

Pakistan has for years invited and hosted Hurriyat Conference leaders, Indian government representatives and Opposition parties on its national day, the anniversary of the Muslim League's 1940 resolution for a separate country.

Traditionally, New Delhi has deputed ministers of state for external affairs - like Singh - to represent India at the celebrations.

But Modi took the final decision today only about 6pm, after which a senior official confirmed by text to The Telegraph that Singh was "likely to go" to the high commission.

That decision came after an initial view in the government to skip the celebrations completely was first overturned and then revived before being finally dumped, three officials familiar with the developments said on the condition of anonymity.

Sandwiched between these see-saw discussions was a letter Modi had sent his Pakistani counterpart in the morning, wishing him on Pakistan Day - a warm gesture that made the cold vibe in the evening harder to justify.

"It was a bit of a back-and-forth," one of the officials acknowledged. "It was a difficult decision either way, because of the public sentiment some of the television studios were trying to whip up."

One channel ran programmes through the day declaring Pakistan as the "enemy" and accusing Indians participating in the Pakistan Day celebrations of joining a "party with the enemy".

But the challenge the Modi government faces even in keeping up tradition stems also from its own decision last August to call off foreign secretary talks with Pakistan after the country's high commissioner, Abdul Basit, met Hurriyat leaders on the eve of the dialogue.

India has long allowed Pakistani diplomats and visiting leaders to meet Hurriyat leaders while insisting that any resolution of disputes between the nations must be strictly bilateral.

In cancelling the talks last August, the Modi government had laid down a new red line that Pakistani officials later emphasised could not politically be accepted by any Prime Minister in Islamabad. Effectively, that red line had killed any possibility of a dialogue.

Modi deftly sidestepped the line by sending foreign secretary Subrahmanyam Jaishankar to Pakistan earlier this month on what he called a "Saarc yatra", without any precondition barring Basit from meeting Hurriyat leaders.

The external affairs ministry argued that the red line was meant for bilateral talks - though unofficially, several diplomats acknowledge that the August condition has tied India's diplomatic positioning in knots.

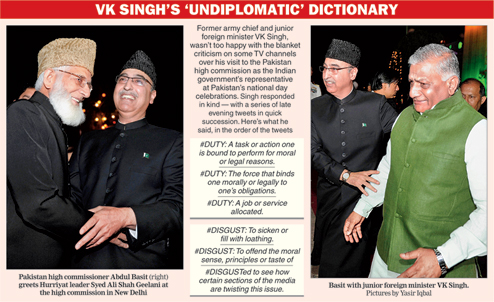

Days after Jaishankar's visit, Basit met Hurriyat leader Syed Ali Shah Geelani to "discuss the foreign secretary talks", a Pakistani high commission statement said.

India's foreign ministry hadn't been surprised when Basit invited Geelani and other Hurriyat leaders to the Pakistan Day celebrations, but the government was preparing options to manage any fallout from public sentiments against their participation.

Threatening not to send any government representative to the celebrations if the Hurriyat leaders participated could work, lobbies within the government argued, officials said.

On Friday, foreign office spokesperson Syed Akbaruddin hinted the government was readying a "surprise" in response to Pakistan's invitations to the Hurriyat.

"I think, in decision-making, surprise is always an element that needs to be taken into consideration," Akbaruddin said. "I am not going to let off the surprise right now for you. Wait and watch."

But by this morning, as it became evident that Pakistan would not withdraw its invitation to the Hurriyat leaders, Modi wished Sharif through a letter.

"It is my firm conviction that all outstanding issues can be resolved through bilateral dialogue in an atmosphere free from terror and violence," Modi wrote.

As a candidate for Prime Minister, ahead of the Lok Sabha elections, Modi had frequently targeted Pakistan as also the then Manmohan Singh government for talking to Islamabad.

The next twist came within an hour, when television reporters accosted Basit at the high commission and asked him about India's concerns on Hurriyat leaders participating at the evening event.

"I don't think India has objected to us inviting the Hurriyat," Basit said.

Within an hour, Akbaruddin responded with a terse statement. Asked about Basit's comment, the foreign office spokesperson said: "The government of India prefers to speak for itself."

He added: "There should be no scope for misunderstanding or misrepresenting India's position on the role of the so-called Hurriyat. Let me reiterate - there are only two parties and there is no place for a third party in resolution of India-Pakistan issues."