Dimapur: First it was the British. Then the Christian missionaries. Then the Indian state they had never asked to be a part of.

For centuries, the indigenous Naga people of India have struggled to preserve their culture against external forces.

Now, Nagas are trying to reclaim a part of that lost history, but the process has been anything but straightforward.

Their efforts to repatriate ancestral remains, which have been in a British museum for more than a century, have been “a trigger for the Nagas”, said Dolly Kikon, a professor of anthropology at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who is Naga herself.

Naga society has changed immensely since those remains were taken. To contemplate their return means reckoning with those changes, and with how many of them are the result of external forces and violence.

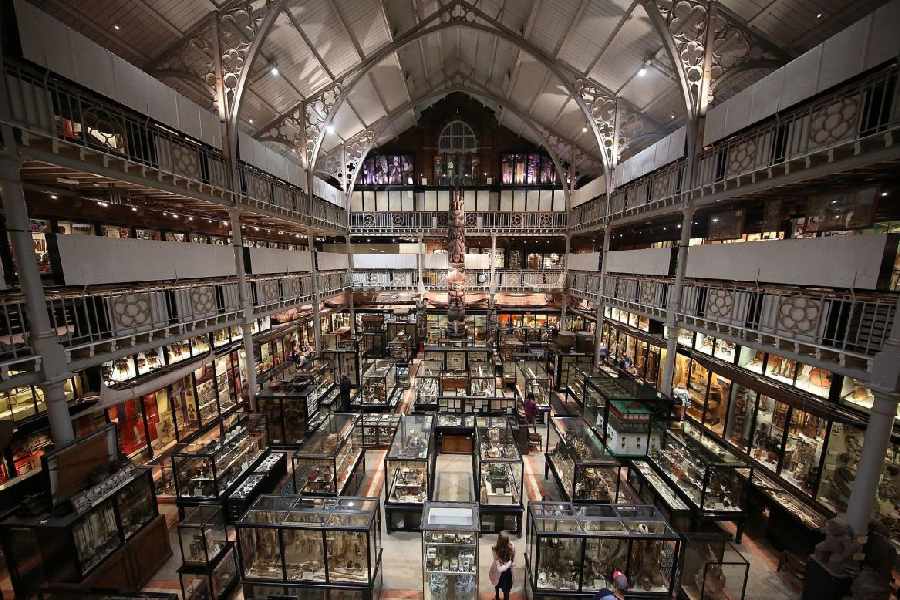

Members of Naga communities in northeastern India have worked for five years with the Pitt Rivers Museum at the University of Oxford, whose collection of Naga cultural objects is the largest in the world, towards the goal of repatriating the hundreds of human remains in the collection. In June, a delegation of 20 Naga leaders, elders and scholars visited the museum and saw those objects for the first time.

“I stood there beside them quietly, feeling a deep sorrow in my heart,” Kikon said.

The human remains in the collection, which number more than 200, include a warrior’s cranium, a woman’s skull decorated with buffalo horns and a piece of skin with hair attached.

Naga tradition holds that human remains are sacred, carrying life and spirit. “They are restless, the spirits will not be in peace unless they find a resting place,” said K. Ongshong, a Naga elder from Longleng village in Nagaland.

Most of the remains were donated to the museum by J.P. Mills and J.H. Hutton, British colonial administrators in northeastern India. While some were given to the men as gifts, most were collected against Naga people’s will during military expeditions into villages, according to experts.

For years, the skulls were included in a Pitt Rivers exhibit titled “Treatment of Dead Enemies,” under the label “headhunting trophies” alongside remains from other indigenous groups, including the well-known shrunken heads of the Shuar people of South America.

That changed in 2020, when 120 of the human remains in the collection, including the shrunken heads and Naga remains, were removed from display and put in storage. In their place stand blue information boards explaining the contentious collection and the museum’s decolonisation efforts. “These displays didn’t match with our values any more,” Laura Van Broekhoven, the museum’s director, said in an interview.

Headhunting was practised among Naga warriors, who collected the heads of enemies they killed in raids or war. (Despite the labelling by the museum, experts said it was unlikely that all the Naga skulls were enemy trophy heads; some may have been taken from burial sites.) Because of the gruesome nature of the practice and the way it helped to feed a persistent stereotype of the Nagas as violent and warlike, some Nagas are hesitant to bring the remains home.

The repatriation discussions are also touching on deeper wounds for many of the Naga people, who number around 2.5 million. That is clear from the difficulties raised, in this case, by one of the first questions in any repatriation process: Where should these objects go?

Today, most Nagas live in Nagaland. But Naga communities can also be found in the states of Assam, Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh — and Myanmar. Before the British colonists drew their borders, the Nagas lived in the Naga hills, now divided among those modern states.

Akum Longchari, a peace and conflict activist based in Nagaland, said Naga society had been in a constant state of struggle since British colonisation in the 1800s. “Nagas have had no time for reflection,” he said, adding, “One coloniser left and another took their place right after.”

Another factor complicating the repatriation process is the enduring legacy of American Christian missionaries, who first arrived in the Naga hills in the 19th century.

If the remains are laid to rest, some Nagas wonder, what funeral rituals should they be accorded — the rites of Christianity, since that is the religion most Nagas now follow, or traditional, animistic ones?

Knowledge of those older rites may now be limited, since the missionaries changed the region’s culture along with its religion, said Nepuni Piku, a human rights activist.

“They did not just come with their Bible, but with their cultural baggage,” Piku said. Naga culture was painted as backward and outdated, Christianity as modern, which led to the abandonment of many Naga cultural practices and rituals, he said.

Naga activists and scholars, along with the Forum for Naga Reconciliation in Nagaland, a civil society organisation, have been trying to build consensus on these questions and more. Once there is agreement on a plan for repatriating the remains and artifacts, a claim will be made to the university. If the university accepts the claim, then the governments of both countries will get involved.

Nagas’ discussions with the Pitt Rivers Museum have also been an attempt to reconcile with the past. But the return of the remains in the museum’s collection could conceivably take decades. The fastest repatriation the museum has ever carried out took a year and a half, while the longest — the repatriation of Tasmanian human remains — took 45.

The Naga delegation to the museum opened its June visit with an Indigenous chant that alludes to the original parting of the Naga ancestors from their creator. The chant concludes with the hope that the ancestor will be reunited with the creator and help to heal the wounds of the past.

“I don’t know if the process of repatriation will do the healing for us,” Kikon said. “But I do know there’s a lot of trauma and we need the healing.”

New York Times News Service