Lakshmi, a 32-year old female elephant, arrived from Karnataka’s Tumkur district after a 500-kilometre journey to lead the annual Bibi ka Alam procession in Telangana.

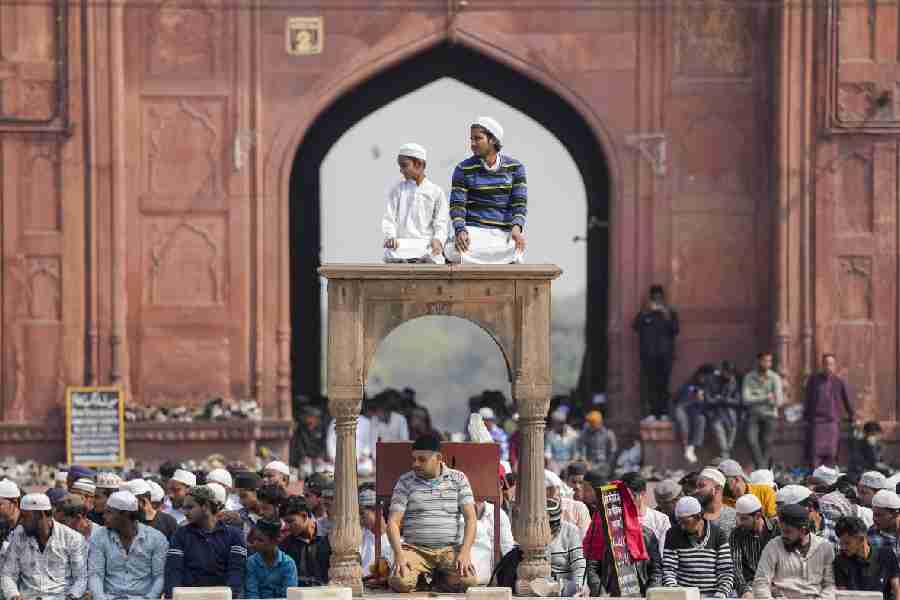

Mounted with a bejewelled plaque, Lakshmi joined a tradition that dates back to the 17th century Golconda era when elephants were used to lead Islamic religious processions in Hyderabad.

Just days earlier, in the congested lanes of Ahmedabad, another elephant had gone on a rampage during the Jagannath Rath Yatra. Startled by loud DJ music and the narrow chaos of Khadia’s old quarters, the animal broke away from a group of 18 elephants, charged into the crowd and injured at least two people.

Mahouts and forest officials struggled to control the animal. The elephant was eventually tranquilised and removed, but not before video footage captured it running toward devotees as people scrambled for safety.

The procession resumed shortly after with the remaining elephants and a heavy deployment of 23,000 police officers, 41 drones and 25 AI cameras meant to monitor crowd behaviour in real time.

Despite these high-tech precautions, the moment revealed what has become an increasingly common spectacle in India’s religious festivals: elephants used as symbols of sanctity and tradition.

A national pattern of panic

The incidents in Ahmedabad and Hyderabad are not isolated.

They are part of a troubling pattern stretching across years and states. In 2024 alone, at least 14 captive elephants were reported to have turned violent, often reacting to heat, loud music, long hours of standing and overexertion.

In early 2025, at least six people died in Kerala due to similar episodes involving elephants in festivals.

Even during the pandemic years, between 2020 and 2021, records show the deaths of 20 to 29 elephants annually, many attributed to stress, injury and mishandling during processions.

PETA India, which has long campaigned against the use of live animals in religious rituals, renewed its appeal this week.

In a letter to the organisers of Hyderabad’s Muharram procession, the group requested the use of a mechanical elephant instead. “With realistic appearance and functions, these mechanical elephants can replicate the experience of a real animal. They can shake their heads, move their ears, swish their tails, and also lift their trunks,” the letter stated. Earlier in June, following the Ahmedabad incident, PETA had offered Gujarat authorities a similar solution...a life-sized mechanical elephant for future Rath Yatras.

The elephant as a religious fixture

The elephant's role in religious culture in India is profound and complicated.

In Hinduism, elephants are not only associated with Lord Ganesha but also seen as sacred beings, often leading temple processions and chariot parades.

In Islam, though elephants are not symbolically central, regional traditions such as the Golconda-era processions in Hyderabad have adopted the animal as a ceremonial carrier of the Alam, a sacred relic.

This convergence of religious practice, sentiment and spectacle has made reform difficult.

Sreedhar Vijayakrishnan, a scientific advisor to the Oscar-winning documentary The Elephant Whisperers, had earlier told The Telegraph Online that elephants subjected to long hours of standing in heat, exposed to loud sounds, and deprived of rest or free movement are likely to exhibit stress responses. “Eventually, the body gives out,” he said.

That warning seems to echo in every new incident.

In Kerala, between 1997 and 2022, over 1,300 human deaths have been attributed to elephants in temple processions and festivals.

A report from the Karnataka Elephant Task Force highlights the systemic gaps in welfare enforcement for captive elephants, including poor veterinary access, ill-fitting shackles and physical abuse with traditional tools like the ankush.

Even when courts have restricted the use of captive elephants, some organisers bypass regulations by borrowing animals from out-of-state trusts and temples.

In Kerala however, several temples have replaced live elephants with animatronic replicas, crafted with metal and fibre. These units can mimic key movements and are often operated by motors or remote control.

In the last two years, PETA has reported that at least 17 such mechanical elephants are now in regular ceremonial use across southern India.

But for many religious bodies, the symbolic weight of the live animal remains irreplaceable.

The grandeur, the perceived blessing, and the cultural weight of an elephant leading a divine procession are hard to let go.

Lakshmi will remain with the Telangana government for four more days. No accidents have been reported yet.