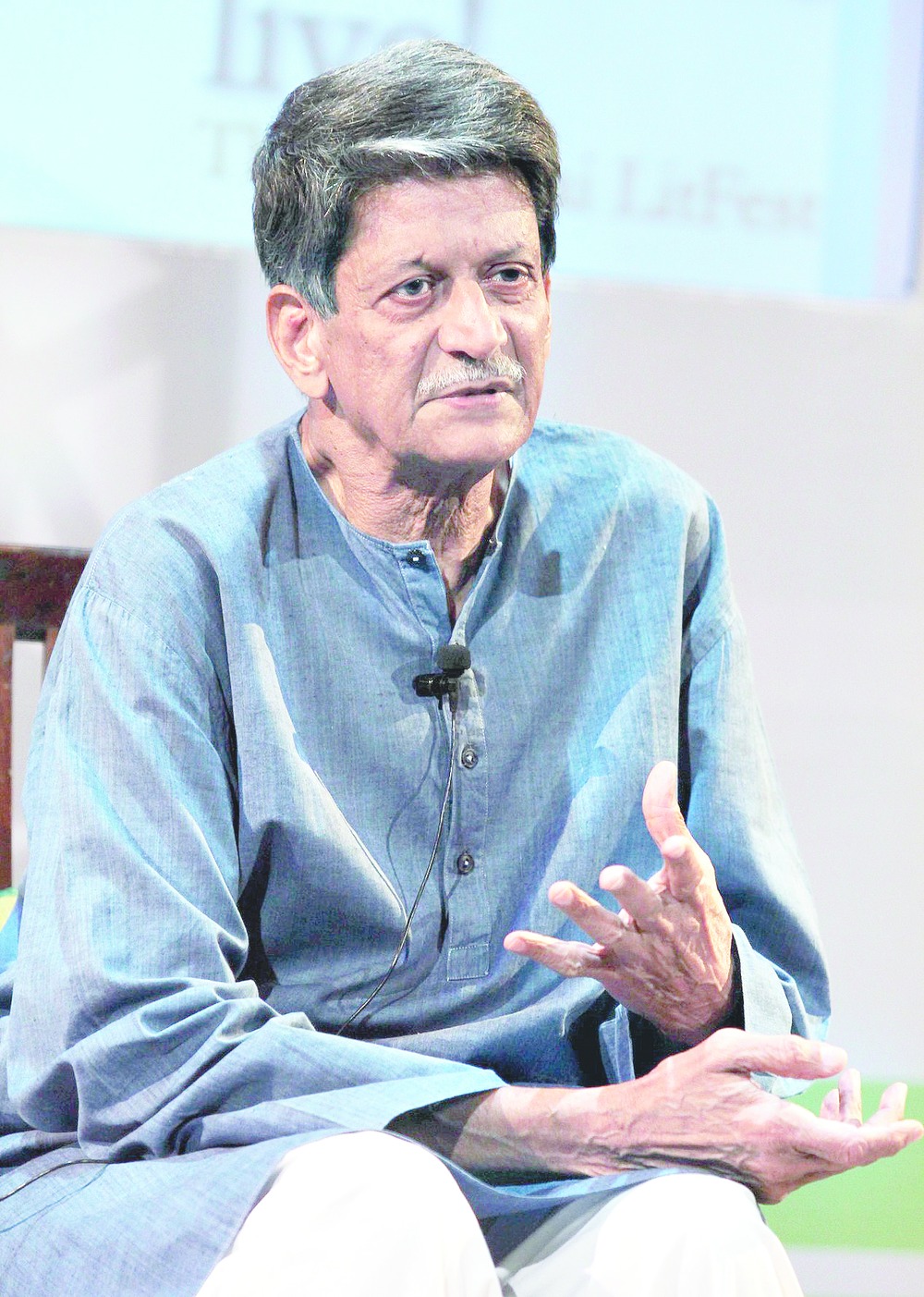

Calcutta, Oct. 28: At the time of Emergency, Kiran Nagarkar wrote a play called Bedtime Story, based on Mahabharata. The Shiv Sena and other fundamentalist parties did not allow it to be performed for the next 17 years.

"I used the stories of Mahabharata on the basis of which I tried to parley my own notion of responsibility. The Shiv Sena and other people banned it, but I am not just talking about the ban," says Nagarkar, speaking over the phone from Mumbai.

In his play, the Pandavas and the Kauravas were not easy moral opposites. Together they represented a duality, both dark, one side a shade darker. It upset the Shiv Sena.

But Nagarkar, who is a Sahitya Akademi award holder, brings the conversation back to before the ban, to why he wrote, to responsibility. "As early as 1977, one thing I realised was extremely central to my life and thinking is that each one of us must accept that we are responsible for anything that happens on the face of the earth." More so in a growing atmosphere of intolerance.

"Democracy does not come without a cause," says Nagarkar, author of Saat Sakkam Trechalis (1974; considered a milestone of Marathi fiction by many) and the English novels Ravan and Eddie (1994), Cuckold (1997) and God's Little Soldier (2006).

If Bedtime Stories earned a ban from Hindutva fundamentalists a decade before Salman Rushdie achieved his fatwa, Ravan and Eddie, which is about two young boys from a Mumbai chawl, one a Hindu and another Christian, romping through their city and adolescence, was criticised for being both anti-Hindu and anti-Christian. Cuckold was about Meerabai's husband, a sobriquet not usually bestowed on him, and God's Little Soldier was about a young man addicted to forms of extremism. Nagarkar won the Sahitya Akademi award for Cuckold.

He does not think of artists as superior to the common citizen in any way. "At the same time, the responsibility of the writer is far greater. From Greek mythology to our mythology, the act of creating something is a divine gift. If you can write, you have even more duty to stand up for the freedom that is the breath of our democratic life," he says.

"Why are we persecuting the Muslims? When a Muslim man has been appallingly murdered and on top of it the murder is defended, how can there not be an outrage at the topmost level of our government?" he asks.

"If someone is going to say 'Oh, that's so sad', it's not enough. Any death of this manner, whether it is Gandhiji's or a common man's, is absolutely unjustifiable.

"But in India there are not too many platforms, unless you happen to belong to a political party, or an activist organisation, from which you can register your protest.

"One way is by writing an article. Another is by giving up an award like the Sahitya Akademi's. For that's what democracy means: it leaves one with a choice.

"But when a writer sees that human rights are being violated left, right and centre, for there is a pattern and there is a barrage, then he should wake up," says Nagarkar.

And censorship is the worst enemy of any art whatsoever, because it shrinks and narrows your own mind. "You say: 'I can't write about Shivaji.' I think this is the responsibility of the Sahitya Akademi. Nobody, but nobody, should even remotely tell writers what to write. When a Sahitya Akademi member from Karnataka (M.M. Kalburgi) was murdered, along with two other very fine writers (Govind Pansare and Narendra Dabholkar from Maharashtra), where was the voice of the Sahitya Akademi?"

Let each person make up his mind about how to protest. "But there is something going on in the country that is thoroughly undemocratic and utterly reprehensible."