The Narendra Modi government, which recently found itself stymied by the public outcry against its controversial move to raid the capital reserves of the Reserve Bank of India, has now cast its eye on another cash hoard.

This is the compensation cess corpus under the goods and services tax (GST) regime that was meant to cover any shortfall in revenues earned by the states during a five-year transition period starting July 2017, when the tax reform was introduced.

In August, the Modi government had cleverly pushed through an amendment to the legislation on the GST compensation cess that gave the Centre the right to stake claim to “the unutilised (amount) in the Fund at any point of time in any financial year during the transition period”.

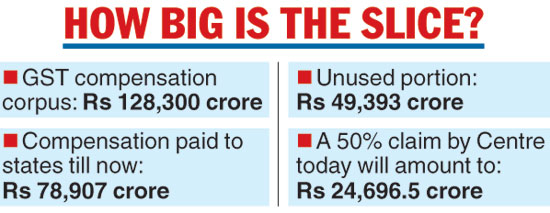

The cash hoard has swelled to Rs 1.28 lakh crore in the 16 months since the GST was introduced.

The GST Act had promised states a projected nominal growth in revenues of 14 per cent per annum over a period of five years from the date the GST regime came into effect. The compensation payable to the states was to be calculated after taking the financial year ended March 31, 2016, as the base year.

The so-called transition period ends on June 30, 2022.

Under the original plan, it was agreed that 50 per cent of the unused sum in the non-lapsable compensation cess fund “at the end of the transition period shall be transferred to the Consolidated Fund of India as the share of the Centre and the balance 50 per cent shall be distributed among the states in the ratio of their total revenues from the State tax or the Union territory Goods and Service tax as the case may be, in the last year of the transition period”.

Obviously, the Centre could not have claimed any amount from the fund until July 2022.

Not any more. The August 9 amendment in the compensation cess legislation — introduced and passed on the penultimate day of the monsoon session — means the Centre can now claim the unused amount at any point of any financial year.

No state protest

When Piyush Goyal moved a stack of legislative amendments to the GST Act and subsidiary laws, the debate had focused on the cuts in the GST rates and legislators had missed the opportunity to question the Centre’s motive for empowering itself with the right to tap into a fund that had a very specific purpose: compensating states for any loss of revenue.

The compensation kitty was the biggest selling point that persuaded the states to accept the principle of cooperative federalism and agree to subsume their taxes under an overarching GST legislation in order to work towards the goal of creating a pan-India common market.

Under Section 7(2) of the compensation cess legislation, the “compensation payable to a State shall be provisionally calculated and released at the end of every two months period, and shall be finally calculated for every financial year after the receipt of final revenue figures, as audited by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India”.

If any excess amount has been released as compensation to a state in any financial year during the transition period, according to the audited figures of revenue collected, the excess amount so released shall be adjusted against the compensation amount payable to the state in the subsequent financial year, the proviso adds.

The amendment to the GST (Compensation to States) Amendment Bill was passed after the Congress walked out of the House. There was little debate in the depleted House and the bills were passed quite easily.

BJD parliamentary party leader Bhartruhari Mahtab, a member of the parliamentary standing committee on finance who has often debated GST issues in the House, said he was not present in the Lok Sabha on August 9, the day the amendment to the legislation on the GST compensation cess was passed. He said his party had not objected to the move and added that the Centre could not dip into the fund without the approval of the GST Council.

“As far as I understand, the GST Council has to approve this. And it has to be a collective decision of the states,” said Mahtab, adding that the fund itself was a creation of the council and had been ratified by Parliament.

Mahtab did not say whether Odisha would protest if the issue came up before the GST Council next month.

Odisha finance minister Shashi Bhushan Behera said: “The state government will take a stand after the Centre makes the purpose for a withdrawal from the fund clear.”

But the intriguing question remains: why didn’t the legislators stop the move when the bill was moved? The Centre could still inveigle the GST Council into passing its request and bail itself out of a sticky situation.

The payout

States have been paid a compensation cess of Rs 78,907 crore between July last year and September this year.

So, the unused portion in the kitty has now shrunk to Rs 49,393 crore. If the Centre were to trigger its claim to 50 per cent of the unutilised fund today, it would be able to enrich itself by almost Rs 25,000 crore, which would then have to be transferred to the Consolidated Fund of India.

It’s a sum that will come in handy, especially now that the fiscal deficit — which stands at Rs 6.49 lakh crore — has already breached the full year’s target of Rs 6.24 lakh crore.

This has made it imperative for the Centre to find funds from anywhere it can to fill the gap, else it must slash its expenditure drastically over the next five months, which may not be politically prudent before the general election.

It is not clear how the “unutilised amount” in the fund will be calculated in the middle of a financial year to enable the Centre to dip into this kitty “at any point of time in any financial year”.

Any move to transfer funds to the Centre must be ratified by the GST Council — so there still is a provision for checks and balances in the system. The council is expected to meet before Christmas.

North Block officials said the move to press for a transfer of funds could be taken up “nearer to the budget if there is a shortfall”. They are hoping the kitty will grow by then and the Centre could hope to tap nearly Rs 50,000 crore.

The Telegraph