Thursday, 22 January 2026

Thursday, 22 January 2026

Thursday, 22 January 2026

Thursday, 22 January 2026

India emerged as the clear winner in the four-day drone-and-missile war with Pakistan that marked the first real test of advanced military technology on the subcontinent. That’s the verdict of three international experts on South Asia who have analysed the conflict and the ceasefire aftermath.

“India demonstrated an ability to deliver precise standoff attacks across large swathes of Pakistan,” says analyst Christopher Clary, writing for the Stimson Center, a non-partisan think-tank based in Washington, which focuses on security issues. Clary adds that it didn’t all go India’s way but it still came out ahead: “Despite Pakistani tactical successes, India appears to have largely achieved its stated objectives.”

Clary offers a day-by-day detailed analysis of the four-day war (he calls it a conflict) and concludes that India probably took a hit on May 7, when the fighting started. Sifting through the available evidence, he believes, “India likely lost several aircraft to Pakistani counterair operations.” He notes that Indian officials have neither acknowledged or denied any losses.

India enjoyed the upper hand for the next three days, concludes Clary, both in defence and offence. “India’s integrated air and missile defence system appears to have largely defeated several waves of Pakistani drone attacks.” Crucially, the defences were, on May 9-10, even able to ward off a few Pakistani short-range missile attacks, he adds. “It seems more likely than not that many or perhaps all Pakistani ballistic missiles employed on May 10 were intercepted or they missed,” he said.

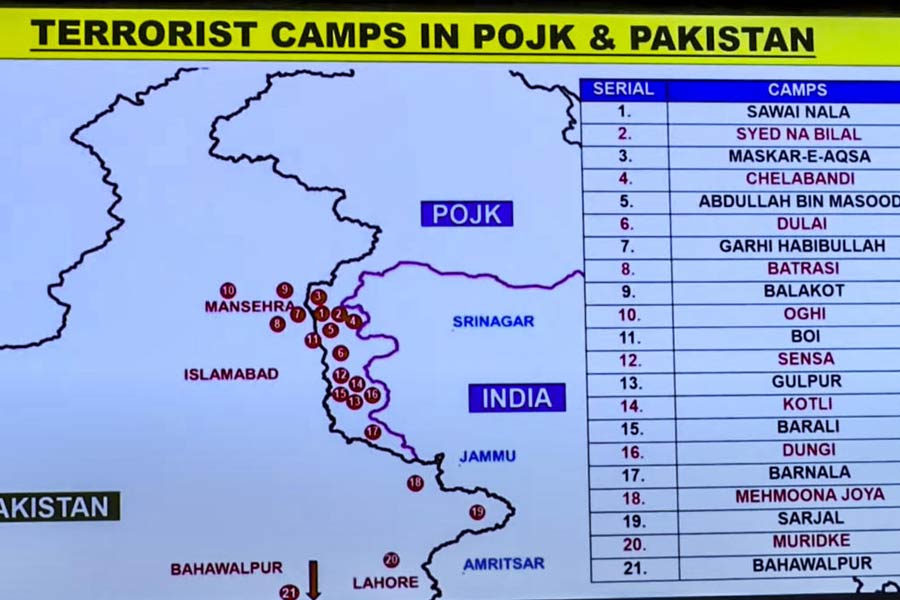

Walter Ludwig, of the influential London-based security think-tank Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), also reckons that the Indian Air Force performed creditably right from the start and that its first strike against the terrorist headquarters in Muridke and Bahawalpur was a spot-on success.

Ludwig reckons that the IAF “demonstrated a credible capacity to identify and destroy what New Delhi characterised as terrorist-linked infrastructure in Pakistani territory, employing stand-off weapons to deliver precision strikes at speed.”

He goes even further to credit the IAF with greater successes, saying: “In the following days, operations expanded in scope, penetrating Pakistan’s Chinese-supplied air defence network to target select forward airbases for the first time since the 1971 war.”

The IAF definitely came out on top over Pakistan, according to Ludwig, who says that losses “must be evaluated against the scale and complexity of the mission.” Additionally, he points out the fact that the IAF, “could strike targets under defended conditions and undertake follow-on attacks demonstrates its capacity for coercive precision operations.”

Similarly, Clary concludes from the evidence available that apart from the “apparent downing” of Indian aircraft on May 7, “Pakistan inflicted virtually no observable damage on Indian military units or facilities.”

Both sides were trying to avoid an all-out war and attempted to keep escalation within controlled limits. On the first day, India carefully did not strike Pakistani military installations. Clary suggests that both sides were reasonably successful at this as they worked to “calibrate escalation and showed some ability to manage escalation adequately.”

Ludwig insists the IAF scored its successes even though its pilots were “under strict rules of engagement that prohibited initiating attacks on Pakistani aircraft or pre-emptively suppressing air defence systems. This decision – to accept heightened operational risk in order to confine the conflict strictly to terrorist-linked infrastructure – is telling.”

Joshua T. White, a fellow at the Washington-based Brookings Institute, focuses on the fact that “Indian weapons not only crossed the international border but also demonstrated accuracy against defended sites. The Indian Air Force was able to strike Nur Khan air base in Rawalpindi – not far from Pakistan’s army headquarters – and other key airfields.”

Clary adds that, despite Indian denials, the US almost certainly played a big role in halting the fighting. It’s clear, he says, that neither side was looking for a longer war.

But this was a war unlike any of the India-Pakistan encounters or battles of the past. Both sides used the latest technology that has transformed warfare.

One Indian analyst reckons that over 100 aircraft were involved in what may have been the largest aerial dogfight since World War 2. Extraordinarily, the dogfight took place at long distance with both sides staying within their own airspace.

Forget about Battle of Britain images of Spitfires and Messerschmitts weaving around one another. If an Indian plane was downed it may have been shot down by a missile fired from a distance of almost 150km.

The power of drones and missile warfare was first demonstrated in the Azerbaijan-Armenia conflicts, which escalated in 2016. Azerbaijan showed how missiles would rule the battlefield by launching hundreds at its enemy. That war opened the Indian armed forces’ eyes to the shape of future conflict and they began acquiring huge numbers of drones and also missiles. The Russia-Ukraine war confirmed what Indian military thinkers had already figured.

Importantly, Clary also points out that the India-Pakistan conflict has been the first time that Chinese military equipment was battlefield-tested against western weapons.

But while India seems to have got the upper hand in the fighting, it only managed to get an odd trio of Israel, Afghanistan and Taiwan to come out openly on its side.

Nevertheless, the three analysts insist that India shouldn’t take the lack of loud expressions of support to heart. Pakistan’s reputation globally has sunk so low over the last two decades that nobody really believes its protestations of innocence.

White puts it bluntly: “The United States and India’s other key partners have, over the last decade, largely adopted New Delhi’s approach of imputing culpability for terrorist attacks to Pakistan, based on a long-standing pattern of Pakistani support to anti-India militancy rather than on publicly disclosed evidence.”

The US has had its own problems with Pakistan, particularly when its troops were in Afghanistan. By contrast, India’s economic development has turned it into a useful global partner. Says White: “The United States’ prolonged exposure to Pakistan-based terrorist groups, and India’s growing appeal as a strategic and trade partner to countries around the world, no doubt also contributed to this evolving dynamic.”

Both sides did their level best not to escalate the crisis but it still intensified at alarming speed because of the new hi-tech weaponry they were using. That could bode ill for the future. Says White: “The widespread use of drones and loitering munitions has complicated how both militaries interpret the escalation ladder,” Each of these developments could make the next crisis more unpredictable than the one we just experienced, he said.

“Should another attack occur, New Delhi may feel compelled to reach deeper into its playbook, and deeper into Pakistan, to find sites with comparable political and operational value,” White added.

This could lead to targeting Pakistani military or intelligence facilities, increasing the risk of rapid escalation.