The number of registered voters in the first Lok Sabha polls was just over 173 million — a fraction of the 968.8 million voters registered for the 2024 polls. Even so, the task was formidable.

The foremost challenge was the geographical vastness of the newly carved nation with poorly connected cities, towns, kasbahs, villages in remote hills, islands, deserts and wasteland. The inhabitants were mostly unlettered (84 per cent of the electorate), and not expected to cast their votes intelligently and secretly. In addition, identifying and registering the names of a vast majority of the people was difficult because lakhs of them had lost their identity documents in the turmoil of Partition. Above all, there was a political challenge: even though India became independent in 1947, it was still a dominion till 1950 headed by a British governor-general more powerful than the Indian prime minister. The transition could be completed only after the elections, paving the way for a new democratic republic.

Sukumar Sen, a seasoned Indian Civil Service (ICS) officer, plotted the elections over many months — from September 1951 to February 1952. This was around the time when the first Prime Minister of Pakistan, Liaquat Ali Khan, was assassinated, plunging the neighbouring nation into a military dictatorship.

Former chief election commissioner, S.Y. Quraishi, calls Sen the “father of the Election Commission of India (ECI)” in his book An Undocumented Wonder: The Making of the Great Indian Election. He writes, “We cannot thank Mr Sukumar Sen enough for laying the foundation of the election management apparatus of India without any previously available experience or infrastructure.”

High praise, but the fact is that Sen is a mostly forgotten figure. His contribution finds sporadic mention in government documents, newspaper reports, archives and a few of his own official reports. Nilay Kumar Saha, a professor and fellow at the Indian Council of Historical Research, Delhi, faced immense difficulty while writing Sen’s recently published biography in Bengali, titled Sukumar Sen — Ek Ananya Jibon. He says, “It took nearly nine years to gather the information on him and his work.”

Sen was born in 1898 in Sonarang village in Munshiganj district of today’s Bangladesh. He was educated at Calcutta’s Presidency College and at London University. A gold medallist in mathematics, he was compelled to opt for ICS in order to provide financial support to his family. “He had to fund the education of six brothers and two sisters,” reminisces his grandson Debdatta Sen, an advocate in Calcutta High Court. Debdatta’s father Dipak Sen, a former chief justice of Patna High Court, was Sen’s eldest son.

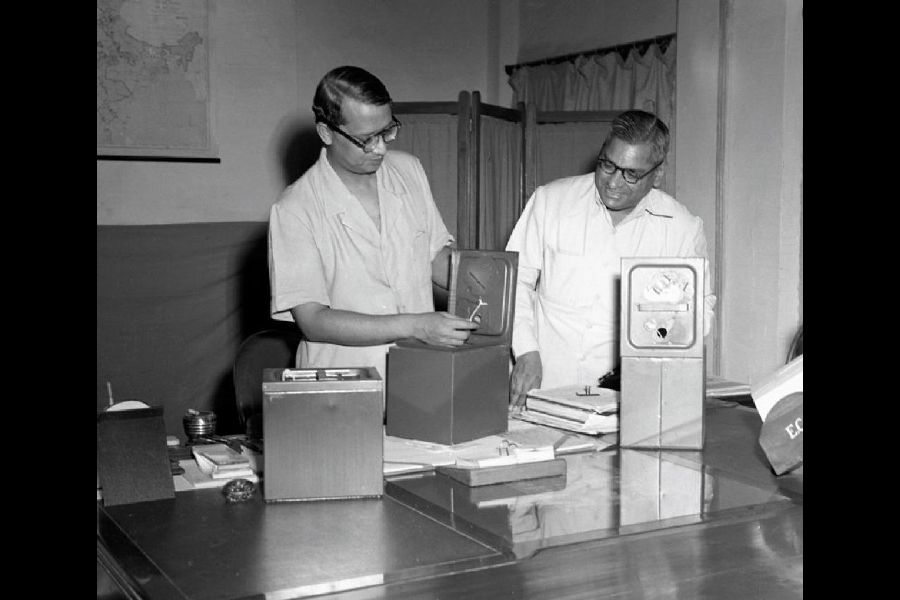

October, 1951, A31A. Mr. Sukumar Sen, Chief Election Commissioner and Mr. P.S. Subramaniam, Secretary to the Commission examining some supplies of ballot boxes specially designed for use in India’s colossal elections. Press Information Bureau archive

Sen first held positions as a district and a sessions judge in Bengal. After Independence, West Bengal’s first chief minister Prafulla Chandra Ghosh handpicked him to be the state’s chief secretary. His mathematical reasoning and style of stern administration impressed Bidhan Chandra Roy, Bengal’s second chief minister too. And when Jawaharlal Nehru was looking for an able administrator to organise the country’s first general elections, he recommended Sen’s name to the Prime Minister.

Nehru was in haste for a quick general election by spring of 1951, but Sen was firm in his decision to defer the election till autumn. After all, he had to build the electoral apparatus — infrastructure, staff, training facilities and so on — from nothing. New recruits of the ECI and other government agencies had to conduct house-to-house surveys across the country to prepare the electoral rolls. It was not easy to involve women since those from conservative families refused to disclose their names. They enrolled themselves as, say, A’s mother, B’s wife or C’s daughter. Sen issued an order to strike off such women’s names from the rolls. As a result 2.8 million women voters were not allowed to cast their votes in the first election.

In a 1956 piece titled “The First General Elections in India and Indonesia” in the journal Far Eastern Survey, Irene Tinker and Mil Walker wrote: “Theresulting furore over the omission of these women’s names was considered a good thing by the Electoral Commissioner; he hopes that the prejudice willvanish by the time the new electoral rolls are complete.”

Since a majority of the voters were illiterate, pictorial symbols drawn from their daily life — such as an earthen lamp or a pair of bullocks — were used to represent a political party. To make things still easier, each candidate was allotted a separate coloured ballot box with his or her name painted on it along with the party symbol. The process required two million ballot boxes at 2,24,000 polling booths.

Sen visited almost every state and ensured mock polls were held. “He introduced the use of indelible ink on a voter’s finger to prevent impersonation,” says Saha. “Sen also used the media — newspapers, radio and a film — to educate the electorate,” he adds. The documentary film was shown in 3,000 cinemas across India to enlighten voters.

The 1951 election turned out to be a grand success. Sen’s meticulous work set the standard for all future elections. According to Quraishi, 80 per cent of the system still remains the way Sen founded it despite multiple electoral reforms over the past seven decades.

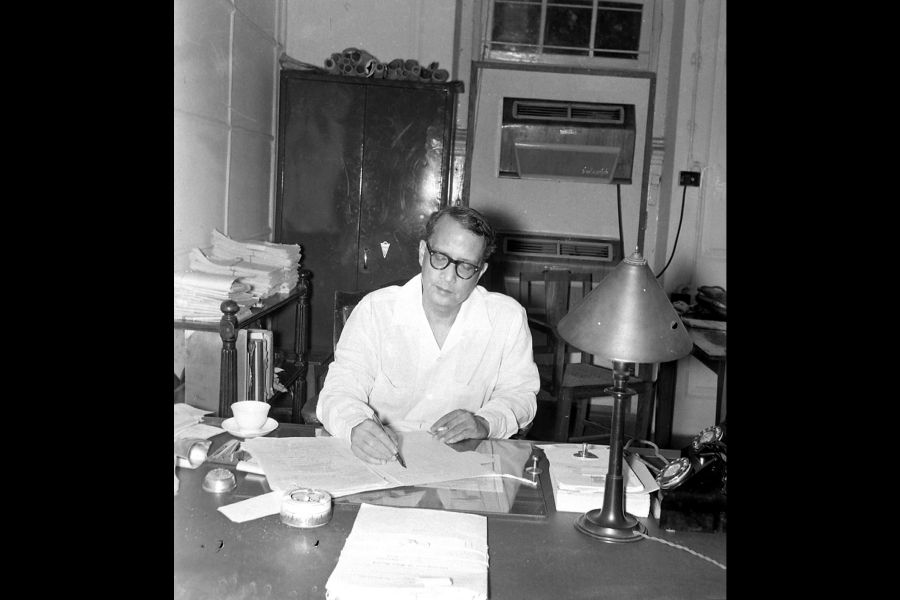

Sukumar Sen, I. C. S. Press Information Bureau archive

Once the elections in India were over, Sen was assigned to supervise elections in Sudan, a country that had just gained independence from British colonialists and whose voters were mostly illiterate, just like in India. He worked nine months there to set up the country’s election machinery and made it work perfectly. Sen returned to India and further refined the election process for the second general elections held in 1957.

Debdatta has faint memories of his grandfather at their house on Bally-gunge Circular Road, built after his retirement. He says, “I was four when Dadabhai died in May 1963. But I have a clear memory of a calm and confident man who never raised his voice.” It is only later that he came to know how firm he had been as head of the family and what a strict disciplinarian he was.

According to Debdatta, Sen and his work are largely forgotten today because he detested publicity. “Like most stalwarts in those days, he chose to stayaway from the limelight. He believed in doing and not talking about the work,” says Debdatta.

After retirement, instead of choosing a peaceful life, Sen accepted a tougher assignment. He became the head of the Dandakaranya project formed by the central government to rehabilitate refugees from East Pakistan in an arid zone of Odisha and Chhattisgarh. It is said the work pressure hastened his untimely death at the age of 63. Just a few days before his death, he wrote a philosophical essay titled What Life Has Taught Me. Here’s a line from it: “A rational adjustment of ambition and contentment is, to my experience, the key to human happiness...”