The BJP’s disdain for the Mughals is known but it had chosen the route, tread by the Mughals to conquer Kashmir, for its own foray into the troubled paradise.

Where the Mughals triumphed, the BJP, fearing an imminent defeat, abandoned its expedition mid-way.

Emperor Akbar’s army is said to have swept up the original road, then a mere dirt track across the Pir Panjal mountains, in 1586 to conquer Kashmir by defeating Yousuf Shah Chek.

That ended the centuries-long rule of Kashmir-centric leaders in the Valley and beyond.

Soon after, the emperor was on his way to Kashmir leading a huge caravan of horses, chariots and elephants to start the dynasty’s love affair with the Valley.

Poonch resident and nomad Manzoor Ahmad, who was grazing sheep at Shopian, returns home to vote four days in advance.

For many Kashmiris, thus began its centuries-old “foreign rule” — Mughals were followed by the Afghans (1753-1819), Sikhs (1819-46), and the Dogras (1846-1947).

The 84km stretch of the road, connecting Bafliaz in Poonch with Shopian in South Kashmir, was made motorable in late 2009 in the face of decades-long purported opposition by the Centre, fearing a direct road link will connect the Muslim majority Valley with Muslim majority Pir Panjal — strengthening the cause of “Greater Kashmir”.

The road remains buried under a thick carpet of snow during winters, closing it for months.

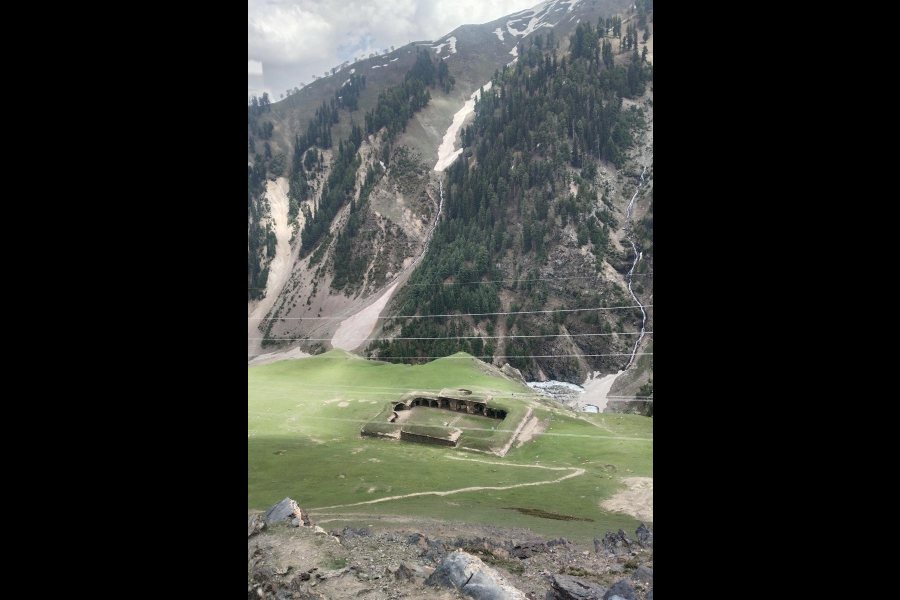

The road criss-crosses the range up to a high point of 11,500ft at Peer Ki Gali, where Kashmir Valley meets Pir Panjal, running past pine groves, lush meadows and gushing streams.

It is dotted by old serais (inns), at Aliabad, Khanpur, Shadimarg and Hirpur, the remnants of Mughal glory, where they stopped and freshened themselves. Hundreds of tourists flock to Peer Ki Gali to savour its breathtaking scenery. Some patches of the mountain remain packed with snow till June.

By conquering South Kashmir, the BJP had set on a mission that would have been unthinkable some years ago. The south was the ground zero of separatist sentiment until the August 2019 scrapping of special status, witnessing hundreds of protests, encounters and deaths.

Electorally, it has been a Peoples Democratic Party turf, where it was helped by the separatist Jamaat e Islami, which has a strong presence.

The BJP seemed to have a plan, though controversial to the brim, to achieve

that. South Kashmir was completely disfigured.

Veteran journalist Mohammad Sayeed Malik said South Kashmir’s disfigurement was one of the momentous, though lesser known, decisions of the central government during the last five years beginning with the scrapping of special status.

A controversial 2022 delimitation took out the rebellious core of South Kashmir — Pulwama and parts of Shopian — and clubbed it with the Srinagar Lok Sabha constituency. Poonch and Rajouri districts (barring two Assembly segments) were clubbed with South Kashmir, which was earlier the Anantnag parliamentary seat.

Now it is called the Anantnag-Rajouri seat, in which more than a half of the 18 lakh voters are ethnic Kashmiris and the rest are nearly equal populations of Gujjars & Bakerwals, a Scheduled Tribe, and Paharis.

Pir Panjal, or Rajouri-Poonch districts, has a big Muslim majority but they are mostly Gujjars & Bakerwals (who are all Muslims) and Paharis (majority Muslims).

The BJP has been courting Gujjars for votes but only with some success. The community gave BJP the first and only Muslim MLA, Abdul Gani Kohli, in the 2014 Assembly elections. In 2022, Ghulam Ali Khatana, a Gujjar, was nominated to the Rajya Sabha in another outreach.

Earlier this year, Parliament gave Paharis and some other groups the coveted ST status, in a first where a language-based group instead of an ethnic group got it. Paharis include high-caste Muslims and Hindus like Peers and Brahmins.

Political observers say the party hoped that support from large chunks of the two communities, in addition to a boycott by majority Kashmiris, might give it a seat.

The Anantnag Lok Sabha seat saw a turnout of 28 per cent in 2014 and 8.96 per cent in 2019, when the 2016 agitation and subsequent unrest further dulled voter enthusiasm.

The quota for Paharis triggered howls of protests

by Gujjars, who feared encroachment into their share. The National Conference added to the party’s woes by fielding veteran Mian Altaf Ahmad, a prominent Gujjar politician and spiritual leader, on the seat.

That, along with reports anticipating a higher participation of Kashmiris in the polls, seems to have forced the BJP to go on the backfoot and decide against contesting.

The constituency is now locked in a triangular contest between Altaf, Mehbooba Mufti of Peoples Democratic Party and Zaffar Iqbal Manhas of Apni Party, which is “friendly” to the BJP.

Mehbooba initially wanted to contest the seat as an INDIA bloc partner but NC was unwilling to budge. The main contest is between NC and PDP.

With the BJP out of the contest, it has put its weight behind Manhas, also a Pahari, looking to open an account through the “backdoor.”

Paharis — who were expected to vote for the BJP en masse — are now up for grabs by the three parties.

The constituency was going to polls on May 7 but it was deferred on request of the BJP and friendly parties – who said the condition of Mughal Road was not good — to May 25.

That was seen as a ruse by NC to prevent thousands of nomad Bakerwals, who migrate to Valley pastures for grazing their sheep and goats in spring, from returning home to vote.

The road has since been largely motorable but on Monday, a landslide blocked it at Chata Pani. But dozens of nomad Bakerwals, including Manzoor Ahmad and his brother, were heading home to Poonch and Rajouri to ensure the victory of their “Peer,” the sobriquet for Altaf.

“We have kept our flock of sheep under the protection of our uncle Lal Hussain at Jabran Shopian. He has already cast his vote (during the Srinagar elections). We are going back to vote for our Peer. Everything else comes second,” Manzoor told this newspaper, sipping tea at Peer Ki Gali, named after Sufi saint Sheikh Abdul Karim. He is believed to have meditated there and there is a shrine dedicated to him.

“Mufti Sahab (Mehbooba’s father Mufti Mohammad Sayeed) gave us this road and the Baba Ghulam Shah Badshah University. We are thankful to him. Par Vote To Hum Peer Sahab Ko Hi Denge (but we will vote for Peer Sahab),” another nomad Talib Hussain said.

Mehbooba on Tuesday took a dig at NC, saying Peer Mureedi (priest disciple) relation should not be exploited for votes.

Journalist Malik said the treatment meted out to Mehbooba by NC (by denying her the seat) has generated sympathy for her (among Kashmiris). Many Kashmiris have earlier blamed her party for bringing the BJP to Kashmir by aligning with it for government formation in 2015. After 2019, she has taken a firm anti-BJP position, criticising it for the abrogation of Article 370 and other issues.

“Her party was literally moribund (after 2019 as it faced the brunt of central crackdown and most of its leaders deserted her to float Apni Party). But the party is suddenly rediscovering itself,” he said.

Anantnag-Rajouri votes on May 25