Sherri Denney was in the fourth day of quarantine in her home in Springboro, Ohio, when she thought about the toll the coronavirus was taking. She sat in her recliner chair and cried as the state’s governor checked off the number of dead and sickened, knowing there would be more the next day. Overwhelmed, Denney, 55, tried to put her feelings into words.

“Wow,” she began writing on an old sketch pad, quickly realizing the precise words would not come easy. “That’s all I can say. My emotions are ranging from sadness to fear to anger.”

The week before, a woman in Nevada turned to her own version of journaling. Mimi J. Premo recorded a video on her cellphone, giving voice to a kind of stunned weariness so many Americans are feeling. And in Indianapolis, in an interview recorded by two university research assistants, a man who is diabetic and HIV positive talked about how the speed and unclear ways of transmission “freaks me out.”

The three accounts, snapshots of intimate moments during the pandemic, are a response to a call from historians and archivists across the country to document this extraordinary moment in history.

Universities, archives and historical societies, ranging from the Smithsonian Natural Museum of American History to a tiny college radio station in Pennsylvania, are rushing to collect and curate the personal accounts of how people are experiencing this sprawling public health crisis as told in letters and journals, audio and video oral histories, and on social media.

They are inviting people such as Denney and Premo to share stories and material from the 2020 coronavirus and its aftermath in real time. The idea is to bridge communal history and offer a fully realized look at the outbreak that can help the public, researchers and policymakers better understand how the pandemic permeated our lives.

Whether a somber handwritten journal or an endearing Instagram post, the contributions will offer a look at a nation attacked by a virus coast to coast. The stories document sickness and death. The profound disruption of American rhythms and rituals, evidenced by empty shelves and streets. The gnawing restlessness of sheltering in place. The ways people showed resilience and managed to still find joy.

“What we as contributors record is what the future generations will remember,” said Mark Tebeau, one of the project directors of a virtual archive founded at Arizona State University.

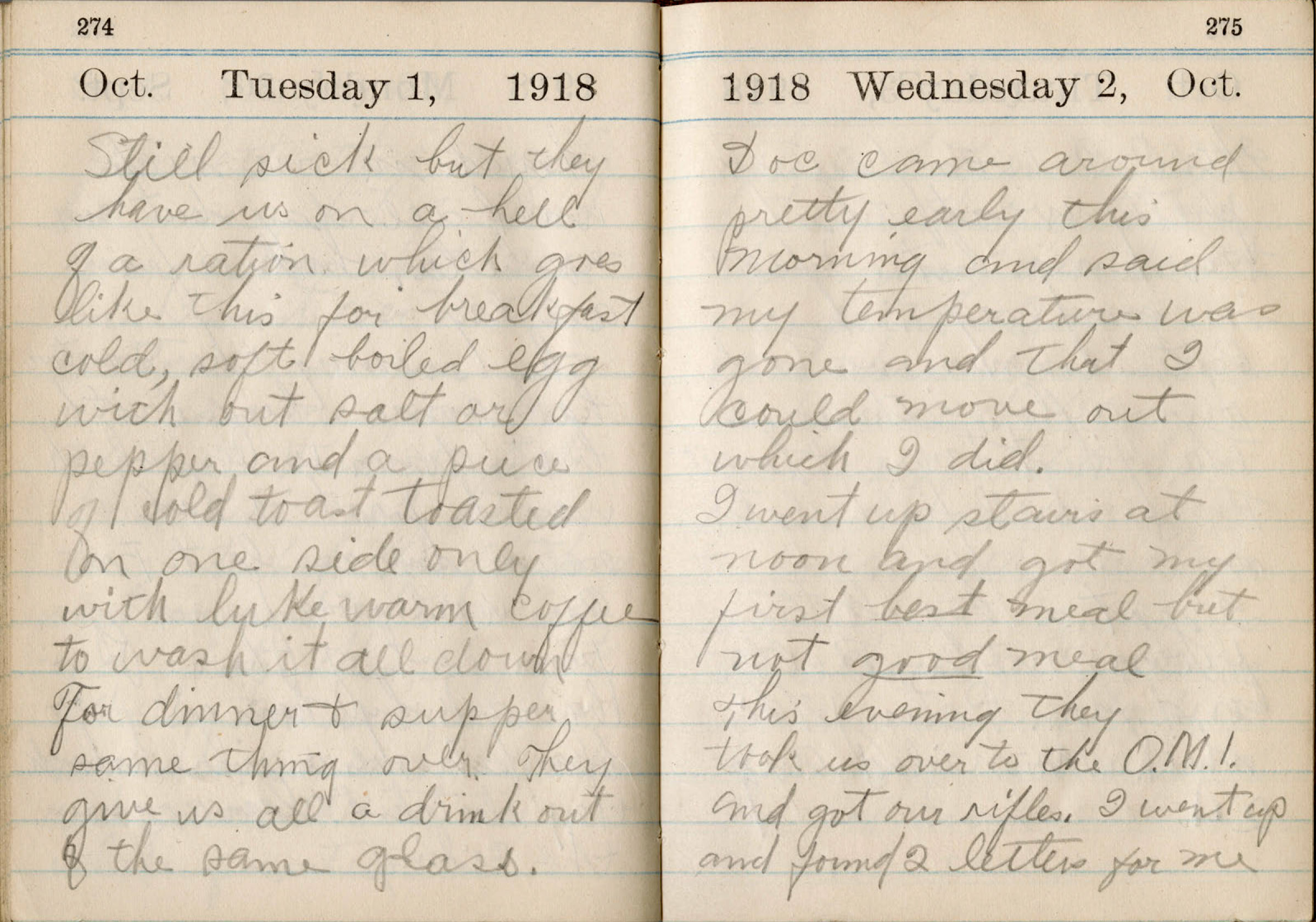

In an undated photo from Wright State University, a journal entry by Sherri Denney. Universities and institutions are inviting the public to share their experiences during the 2020 coronavirus pandemic and its aftermath. (Wright State University via The New York Times)

The team of historians and artists launched A Journal of the Plague Year: An Archive of Covid-19 on March 13, two days after the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus a pandemic. The name was inspired by Daniel Defoe’s novel “A Journal of the Plague Year,” which chronicles the bubonic plague in 1665 London through the lens of one man.

With the help of graduate students and scholars from about 20 universities, the archive has amassed more than 1,400 entries from 500 contributors across the world, including Australia, Peru and China.

Last week, the Library of Congress received its first Covid-19 collection: street scenes from New York, New Jersey and California by the photographer Camilo Jose Vergara. In addition to documenting stay-at-home life, mask styles, health care workers, the economic effect and how people are helping one another, the Library of Congress is also collecting web content, data and maps.

The Smithsonian National Museum of American History deployed a Rapid Response Collecting Task Force to chronicle the pandemic. “Museum staff is working to formulate a plan that achieves a balance between the urgency to document the ephemeral aspects of the historic turning points as they happen,” the museum said in a statement, “and the need to provide a long-term historical perspective.”

Local archives are also calling for oral histories and materials. The Atlanta History Center, for example, is asking the city’s residents for digital files and physical artifacts (the latter would be collected once the center reopens). The project, called Corona Collective, lays out how seemingly mundane items — a no-frills furlough notice, a handmade banner thanking emergency medical workers — help tell the story of how daily life in Atlanta changed.

Similar efforts are cropping up in big cities and small towns. Sometime during spring break in March, Jason Kelly, a professor at the Indianapolis campus of Indiana University, realized the coronavirus was likely to be the defining event for generations. For a professor who teaches digital public history, it meant something else, too: How people experienced the outbreak needed to be captured and organized in a searchable database. That was the seed of what is now the Covid-19 Oral History Project, based at the Arts and Humanities Institute on the Indianapolis campus.

Kelly turned to the 19 graduate students in his digital public history class and asked if they would put other coursework on hold to focus on the project, which uses “rapid response collecting” for Covid-19 lived experiences. Eventually the project will merge with the larger Plague archive.

Such efforts to collect memories in real time was also used by groups after the Sept. 11 attacks, Hurricane Katrina and the Pulse nightclub massacre.

The page from Denney’s diary became one of the first submissions to the coronavirus public memory project set up by Wright State University.

“All of a sudden the pandemic was right here and personal,” said Dawne Dewey, head of special collections and archives at the university. “We put the call out because we need stories to help future generations understand this moment in history.”

The archive, partly housed on the fourth floor of the school library, includes the journals of survivors of the 1918 flu pandemic. One was written by Donald McKinney Wallace, a farmer who served in the Army.

McKinney was sickened with the flu in the fall of 1918. He was quarantined in barracks, separated from others by blankets hung from a wire. He wrote about the daily meal of soft boiled eggs and cold toast, feeling weak, a stubborn fever, isolation and the deaths of fellow soldiers — an account that could have been written today.

“A century ago, people told their stories in written journals,” said Dewey. “Now, we are capturing people’s thoughts and experiences through social media posts, email, audio and photographs.”