My characters are refusing to act their age, my book will never get done, your endless chess-playing is shooing away my concentration, the world is ending. It’s all your fault.

Wait. What, now?

A decade and some ago, in the middle of pouring rains and gathering relatives, we marry. We have known each other for five years, surviving Presidency College and Jawaharlal Nehru University together, and are, as might well be apparent, young and foolish.

In our defence, we don’t know that.

None of our friends are remotely interested in the business of marriage; they are almost embarrassed for us — so seventies! they keep saying — and they appear like anthropologists at our rainy wedding, bearing presents their parents have bought for us and lovingly packed. My best friend has her MA finals the next day and can’t dally; other friends who have promised to come from Delhi use the cyclonic weather to stay away. We grin as the bright light shines into our faces, the shehnai softens, and the jasmine begins to wilt in our garlands in the monsoonal heat; we cannot wait for the future — our future — to begin.

It all begins, predictably, with an empty apartment that needs to be filled, painstakingly, over the months, with objects one might need. But by the time we own a gas connection, several bookshelves and books, an air conditioner, beautiful utensils, multiple bank accounts, EMIs to worry about and a landline phone with broadband, we have changed our minds. We now want to leave our jobs, give away our painstaking acquisitions and become writers, travelling the country on a budget. Real writers need real material, we keep explaining to each other, through the intense evenings at home, where the haze of high idealism hovers dramatically over us, though it is a bit like preaching to the choir. We have already bought the narrative. We need to see the country — for his economic theories and my grand novels — and we need to shock ourselves out of our bourgeoisie dependence on monthly pay checks. Authenticity, that’s what we need.

It is a tough act to sell to the parents.

However, we have not mastered the art of delivering the fait accompli for nothing.

We attempt to become writers, publish a few books. On balance, it is a good thing that we feel nostalgic about the seventies. As a book writer, I’ll have you know, one’s earnings are respectable in socialist-era terms. But while one’s peers are making code while the globalised sun shines, rushing offsite and piling bank accounts, buying their second houses and cars, our book-writing endeavours — slow-moving and tortuous at the best of times — albeit peculiarly joyful, seem long and unnecessarily complicated.

We steadfastly look the other way though and go about our business. We fill our attic with more books, sit in the terrace and complain about past mistakes, and between all the hundred things we must do to subsidise our art, tap away at the laptops. Fear lurks just outside the threshold — but we have learnt to live with it. Except when there are meltdowns. There are often meltdowns. The one thing that you learn while living with another writer under the same roof is that there may not be a roof someday. Concrete might just not be able to withstand the intermittent shock waves that emanate from below.

Below are reproduced three snatches of conversation from our house on a mild February day. (A few expletives might have been removed since our families dutifully read The Telegraph with their morning tea.)

11.30pm

D returns from an excursion with bursting bags.

“Aaargh. Have you bought more books? Where will we keep them? Were the five hundred thousand books we own, and will possibly die buried under, not enough?”

“Yes, I did buy a few. Not that I need to explain my purchases, but I’ll have you know these are for my students.”

“Then what’re they doing here?”

“If they’d given me an office, it’d be there. No need to rub it in.”

“That’s why I keep saying we need to sell more books than we buy. We could have afforded our own offices then.”

“Ah yes, your magnum opus on growth theory will certainly give Chetan Bhagat a run for his money. Did you order the groceries?”

“I did. But they are out of chocolate digestives.”

“Convenient.”

“What was that?”

“You obviously don’t want me to get out of bed tomorrow morning and finish my pending article and grade those essays.”

“Are you suggesting I deliberately forgot to order your chocolate digestives?”

“Not suggesting, stating.”

“Damn right, Roy. I did too. I won’t let you eat that poison any longer. I had a chat with your mother this morning. She concurs.”

At that clearly below-the-belt collusion, D narrows her eyes and delivers the punchline.

“Your publisher called me, Jha. She wants her book. And by the way Modern Bazaar is not the only place in the world that sells dark chocolate digestives. I was prepared for your treachery.”

There is unearthly clatter as both lunge for Roy’s bag.

(It is possible that a long, circuitous, blame-filled conversation results, with several mini and one massive meltdown. It is possible nothing happens, and cups of tea are brewed.)

4.30pm. Tea-time

“By the, way there’s a mail from Freddy. He wants to you to write that piece on India-Israel relations. Quickly.”

“Oh, you mean Modi-Netanyahu relations. Both are rather good at the same thing.”

“And what is that?”

“This chaa is excellent. We’re a good team, all said.”

“I noticed what you did. Of course, the only reason we are a team is because of me. I hold us together.”

“This is exactly the premise upon which world-class teams have fallen apart.”

“Hmph. So now you are suggesting we are a world-class team?”

11.45pm

“Why aren’t you sleeping? Don’t you have a plane to catch early tomorrow?”

“Lit fests, lit fests. Why don’t you come with me?”

“No can do. At least two of my publishers are likely to be there. I can’t dodge them all.”

“Maybe, we should not have gone down this path, you know. We should have just settled down, made babies, brought them up.”

“We still could you know.”

“Not go down this path?”

“Ah, no. Too late to turn. Not too late for the other thing though.”

“Are you sure? It seems like we have lost a lot of time. The days have become months and the months have become years.”

“As they most inevitably do. It only shows that you can’t have it all, all at once. And what didn’t kill us... etc. etc. We have paid our dues, though, I think, and we have some cheques to cash now.”

“Why do you have to be so optimistic? It’s annoying. I hate these oppressive nights. I only wish we had some of those cheques in the past.”

“The past the past! Wake me up when you come to the future.”

“As good a time as any other to ask: will you love me in the future?”

Outside the house, the lane is unusually quiet. The Saptaparni tree sends out its maddening mysterious scent which, it is believed, drives people to crazy ideas. The pigeons nestle under the awnings, cooing and fluffing their feathers if a car goes past screeching too loudly. Spring courses under the earth silently. It will burst into the trees and the terraces soon.

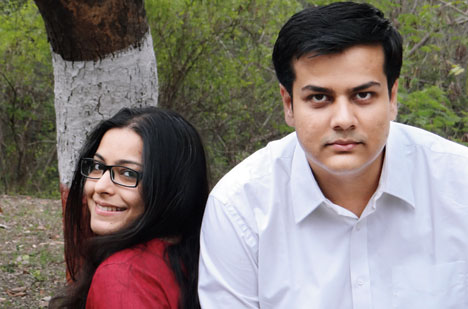

Devapriya Roy and Saurav Jha are writers who live and work in New Delhi while constantly pining for Calcutta. The book they wrote together, The Heat and Dust Project: the Broke Couple’s Guide to Bharat, recounts a part of their crazy journey across India on a very very tight budget