Bansberia and Adisaptagram. The first is a town in West Bengal, 60 kilometres north of Calcutta, and the second is a village adjoining it. Between the two they have 10 edifices that are a combination of private houses, a temple, a club house, a workshop and a community centre. These were built between 2012 and 2021 with fair participation of the people of the area. More such projects are on the anvil, including renovating the local municipal school, the cremation ground and a temple.

In its August 2021 issue, The Architectural Review, a monthly international architectural magazine, devoted a monograph on these projects by Abin Design Studio (ADS) of Calcutta. ADS derives its name from its founder Abin Chaudhuri.

Editor Manon Mollard writes in the monograph: “The story of post-Independence architecture tends to rely heavily on the contributions of Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn, who supposedly ‘set the foundations of modern architecture’ in India. As built monuments, they speak loudly of these architects’ individual journeys… Yet as monopolising narratives they prevented a richer set of ideas and practices from unfolding and compromised the potential future modernities of the Indian subcontinent.”

It all began with bamboos. Bansberia is known to grow an abundance of the plant, as may be evident from the name it took. In 2012, when Chaudhuri was approached by the neighbourhood club to design their Kartik Puja pandal, he created a rainbow installation comprising 1,800 bamboo poles. At night, the structure was lit up with halogen lamps. After the puja, the poles were reutilised to build a fence around the local football ground and favourite trespassing ground of stray cattle.

Soon after, several businessmen of the area thronged to Chaudhuri. One of them asked him to transform his ancestral property to a modern residential house, another asked him to build a new house keeping a towering tree intact.

Chaudhuri took up some of these and also managed to impress upon clients that there was a need to be sensitive to the people and the surroundings beyond a certain structure. When someone asked him to build a garage and residential quarters for live-in helps, he convinced the owner to turn the site into a community building.

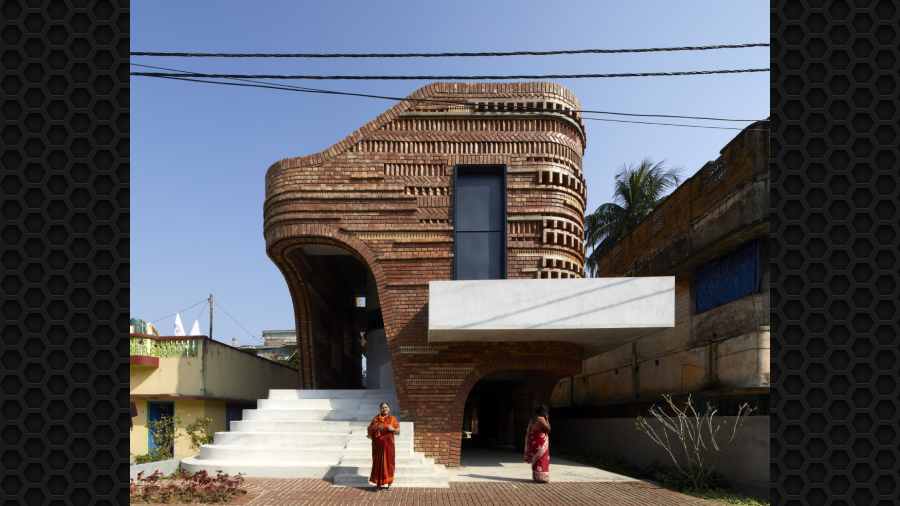

So, on the one hand, the structure is what it set out to be, and on the other, it also weaves itself into the lives of the greater community. It extends onto the street through a series of wide steps, which double as galleries for men, women and children who like to watch a Kartik Puja procession. The structure dives in as well, steps dip into the ground floor that is used as a community hall, while another flight of steps lead to the upper floors that serve as classrooms by day and dormitories at night. The structure called the Gallery House makes extensive use of terracotta inspired by the Hangseshwari and Ananta Basudeb temples nearby.

The Narayantala Thakurdalan is another of Chaudhuri’s creations, an open podium. It came about when the trustees of the thakurdalan requested Chaudhuri to do something about the decrepit structure. The architect got to work and the result was a jafri structure that allows ample space to participate in the religious rituals. Says Chaudhuri, “Accepting exposed concrete as a temple was not easy for them. It came gradually.”

Since then, however, Chaudhuri has discovered that he cannot please everyone all the time. “My mother was not too impressed by my work on the thakurdalan, preferring the earlier more conventional space for devotion,” he says.

To get back to Bansberia and Adisaptagram, several other projects, such as the Waterfront Clubhouse and the Panchayat Society Hall, are design interventions made in collaboration with local communities. Chaudhuri says, “It is important to get their participation from an early stage. It becomes easy to source funds. Besides, one has to get an idea of how they want to utilise the space.”

For the Adisaptagram club, Chaudhuri realised they wanted a gallery. “So what if they are poor, this was their aspiration and I involved them in building one for themselves. The lattice work at Narayantala Thakurdalan happened because the trustees told me that the fumes from the hom (a fire ritual) needed an outlet,” he explains.

The clubhouse and the hall are both public properties. The funds have come from the state government and local patrons have done their bit with building materials and labour.

A. Srivathsan, who is the executive director of the Centre for Research on Architecture and Urbanism, CEPT University, writes in the monograph how the ADS projects mark a “substantial departure from prevalent practices that have lost sight of architecture as a service profession”.

Colombian architect and Leob Fellow from Harvard, G.S.D. Alejandro Echeverri, met Chaudhuri when he was in Calcutta and visited Bansberia and Adisaptagram. In the monograph he writes that he was struck by the shared complexities of Medellin (in Colombia) and Calcutta, complex realities, deep inequalities and difficult political and social issues. “There are undoubtedly many elements, codes and messages, all echoing from our cities of the Global South,” says Echeverri.

Chaudhuri cannot agree more. He adds, “Architecture becomes meaningful when it expands its sphere of influence and transforms not only the surroundings but also the lives of its users — becoming an emblem of generosity.”