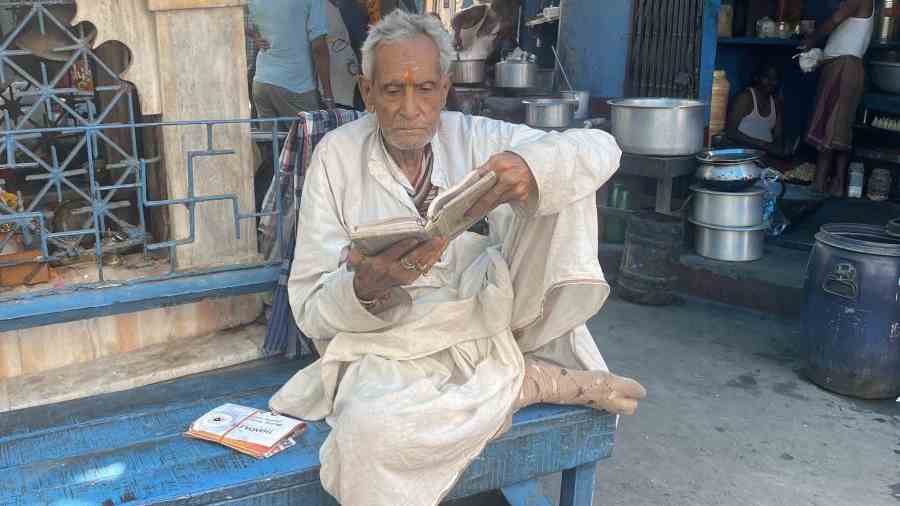

He sits on his perch on any given day like an ancient bird. His itinerant dhoti and kurta are both a smoky white. His shrunken frame of 95 years does not quite fill his shirt and the sleeves flop down like tired wings. His utterances are low-pitched warbles and difficult to grasp; it is only later that he tells me he has no teeth! By mid-morning, the plumage on his head is dishevelled. I am reminded of a Biblical reference: “I am like a pelican of the wilderness: I am like an owl of the desert.”

Should you be making your way through this throbbing vein of central Calcutta on a weekday, in all likelihood you will not see him. He is not easy to spot through the criss-cross of parked cars, motorbikes, the man on the bench peeling potatoes or kundri, the hive of customers outside the tea-cum-sweet shop facing the roadside temple and, of course, the constant arrivals and departures of the faithful to the temple itself.

But sometimes, when the day is winnowing to an end, I have seen him in clear view, minus the hide and seek. Against the marble altar, one foot folded under him, another folded before, face tilted heavenwards as if in mid-conversation with the Maker, palms pressing against the little blue bench he sits on as if readying for a long flight. That’s him — Ramji Pandey, the pujari of the little temple on Sooterkin Street.

Panditji is a great talker but he is not used to talking about himself. Every personal story melds into some kind of universal or the other. So when I ask him if he was born in Calcutta, he replies he is from the same place as Rajendra- babu. Almost immediately, he starts to recite in a sing-song voice a poem he attributes to India’s first President who was born in Bihar’s Siwan district. “Tara ki jyoti me chanda chhupe nahin/Suraj chhupe nahin badal chhayon etc. etc.” Suddenly he stops, switches to his normal voice and slowly quotes what is possibly the last line. “Aur karma chhupe na bhabhoot lagayo… No marker of righteousness or purity can hide one’s actions.”

Another time I ask him if one can become a man of god by virtue of his birth alone or does one have to earn that qualification, but he launches into an anecdote about one gyani patrakar. The journalist came to him and said: “I don’t know how to pray.” Panditji leans in and says in his parched voice: “I told him, ‘My dear fellow, it is you who know how to pray. Just like a mother does not have to be told that her child is hungry because she knows instinctively, the Supreme Mother also recognises a true prayer when She hears one. Ma bhav bojhe’.”

Yes, he keeps switching between chaste Hindi, clear English and good Bengali. He speaks so softly that I cannot take my eyes off him lest I miss a word. But from the corner of my eye, I can see people stopping to offer flowers at the temple and then pausing to hear him speak. They are mostly men, office-goers with bags and tiffin boxes. One or two come forward, touch his feet and leave without a word. Panditji says “He is from Brindavan” or “He has come from Bhowanipore”. Once or twice a greyhead stops by and Panditji clasps his hand fervently and says, “He is my samakalin… contemporary. There are very few left.”

It is end-March, but he is wearing socks and a half sweater. I am more curious about the seven rings on him. I ask what they are for but he appears to think I am asking him about an umbrella hanging from the iron railing behind us. He says, “A Muslim man and his wife had come, after they had prayed the wife offered me this umbrella.” I too jump topic. Does he believe in the equality of religions? He does. Does he share this thought with those who come seeking his wisdom? He replies, “Certainly not. Everyone cannot receive every kind of wisdom.”

Like I said, it is impossible to get any linear tale out of Panditji. But this is what I manage to glean. Our man was born in Bihar, lost his mother when still a boy and moved to Benares. He also spent some of his boyhood years in Calcutta, where his grandfather and later his father served as pujaris at the Rani Rashmoni estate in Janbazar, and then he went to Banaras Hindu University to read Sanskrit. He taught in schools till his father commanded him to take his place as pujari of the Rashmoni Estate. Panditji got married, raised his children, and though he lost his wife some years ago, he continues to live in Janbazar with a grandson and a very obedient granddaughter-in-law.

He came to occupy this fond place on Sooterkin Street possibly in the late 1970s. A “Rajasthani businessman” called Jagannath Daga built this shrine to Shiv and Shakti. (Today, this temple is also home to Saraswati.) The businessman heard Panditji’s pravachan and invited him to be keeper of this temple.

To date, Panditji walks down from Janbazar around 6 every morning. He says with fierce pride how he did not alter his routine even when corona raged. “I shall die on this street, but I will not stop coming here,” he says. What is it that you find here, I ask him. He replies: “Vidwan ghar me nahin milta, bahar hi milta hai.” And god? After so many years of being in god’s service, what is his definition of god? He replies with a smile and a wiggle of a bony finger: “Aap bhagwan hi toh hain.” You are god or god is in you, whichever way you want to read that.