The past has a way of occasionally catching up with the present. Suddenly, without any warning whatsoever, you feel for a few fleeting moments that you have plunged headlong into an episode of history you could never have been a part of. It’s all inside your head. Yet it’s almost tangible.

It happened to me at the Indenture Memorial jetty at the Kidderpore Docks. The past became an overwhelming presence.

It had happened to me once earlier in June 2018 when I accompanied Jeffrey Clark, a friend from Scotland, to visit the abandoned Gourepore Jute Mill near Naihati. In the 1950s, Jeff grew up in one of the many huge bungalows that still dot the compound of what was once the biggest jute mill in Bengal. Now it is nature’s kingdom, with all the bungalows and factories in the fatal embrace of parasitic vegetation. As Jeffrey looked around for his former home, both of us suddenly felt the electrifying presence of the past. Nature seemed to be in empathy as the wind sprang up, the blood red krishnachura blooms wafted down in a shower, and the dark clouds started rumbling. And then the heavens opened.

I realise now that this time, it couldn’t have happened out of the blue. Unbeknown to me, it had been building up for a long time. Perhaps the lurid cover illustration of a black man being whipped by his white master in Tom Kakar Kutir had fuelled my pre-teen imagination. That would be Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin in Bengali. That was the first time I realised that one human being could trade others as if they were commodities.

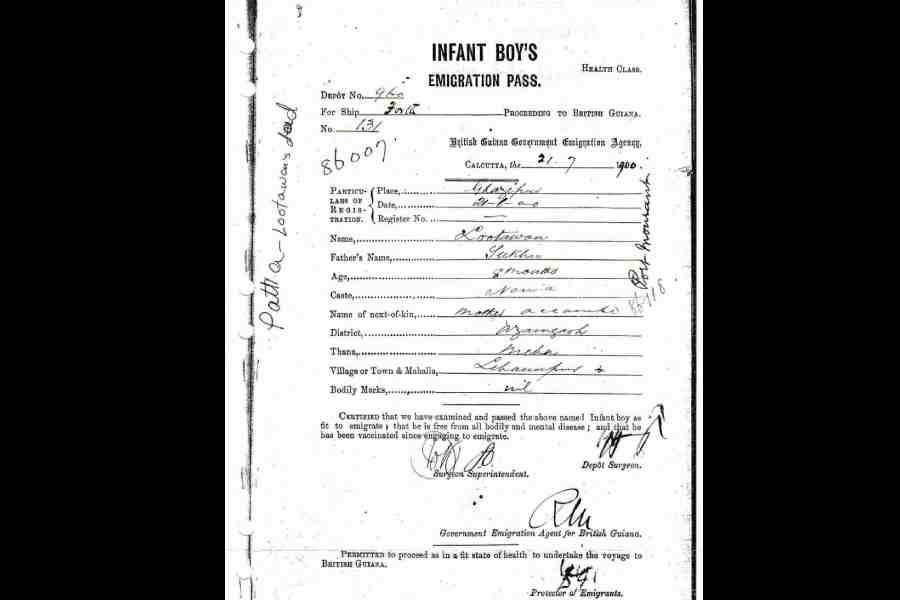

The immigration pass of an eight-month-old. Kolkata Port Maritime Archives Publications

Who knows, possibly A House for Mr Biswas was a major factor as well for the way I was feeling. It was so easy to identify with this man, whose family had been brutally uprooted from India and dumped on a faraway, hostile island a few generations ago to fend for themselves in the plantations.

By law the coolies, as they were called, were not slaves any longer, but that was only on paper. Only the violent and monstrous machinery of colonialism that had stripped entire nations of their wealth and identity could have enforced that. Naipaul’s compassion, not unqualified by irony, for this otherwise weak vessel who was trying desperately to hold his own despite the adversities he faced always resonated with me.

The frenzied clash of the khartal played by upcountry labourers on evenings outside roadside shrines in Calcutta as they relaxed after a day of back-breaking work must have entered deeper inside my brain than I ever cared to acknowledge. This was the kind of music that the labourers deprived of their selfhood would have made in the plantations beyond kalapani or the ocean, which they were forced to cross despite the taboo in late 19th century.

A few weeks before we made our trip, a friend of mine had taken her guest, a composer and teacher who created sound art based on listening to both sound and silence, to Suriname Ghat, one of the points of the Hooghly from where thousands of local people set sail for destinations across the mighty seas to work in plantations. They were promised heaven. They ended up in hell.

All this had been happening since 1834. The port’s docks were yet to materialise, and only a series of ghats and a few jetties existed, and the sound artiste was trying to listen to the voices of the past and record absent sound.

Our — a motley group of heritage enthusiasts — journey to the jetty began at the Maritime Archives and Heritage Centre on Strand Road overlooking the Hooghly. It was March and still not unbearably hot. I was there on the invitation of Gautam Chakraborti, known for his passionate involvement with Calcutta Port’s heritage, and Atreyee Basak and Poulomee Auddy, the two young friends who organise the Ganges Walk, for a ride on the refurbished paddle boat of 1940s vintage. It started advancing almost imperceptibly from the Man O’War Jetty adjacent to the Prinsep Ghat.

Then early evening, a steamer carrying us left Outram Ghat as we moved northwards in the dark. As we reached Shobhabazar, we made an about turn and headed towards the Indenture Labour Ghat in Kidderpore.

Gautam Chakraborti outlined the history of indentured labour. Slavery was abolished in 1833 in the British colonies. But the plantation and mining economy of the colonies needed cheap labour in Mauritius, Fiji, Reunion, Suriname, Jamaica Guadeloupe, the British Guinea and other colonies along the Indian Ocean to the Pacific Islands.

Lila Gujadhar Sarup, who had extensively researched the colonial emigration of the 19th and 20th centuries, wrote: “G.C. Arbuthnot, a private recruiting agent, signed an agreement on September 9, 1834, in the presence of the chief magistrate, and the superintendent of the Calcutta Police, which enabled him to take 36 Hill Coolies to Mauritius. These coolies were illiterate and they were made to affix their thumb impressions on this very first contract…”

The quasi-legal contract was valid for five years. They were meant to get to and fro free passage; Rs 5 per month as wages; six months advance pay; Re 1 to be deducted per month on account of repatriation passage, besides free rations, accommodation and clothing.

“The planters in Mauritius and later on in Natal and other colonies found ways and means to prevent the return of the natives of India… Fourteen ships sailed from Calcutta, taking indentured labourers to Mauritius,” Sarup wrote.

After the Permanent Settlement was brought into effect in 1793, the East India Company allowed zamindars to fix the land revenue. Zamindars terrorised farmers into cultivating cash crops. Famines followed, and the peasantry was forced to look for jobs elsewhere. Hustlers (adkathi) lured them away from their villages. Joining the indentured labour workforce was their only recourse. According to Unesco estimates, from “the 1830s and over a period of roughly 100 years 11,94,957 Indians were relocated to 19 colonies”.

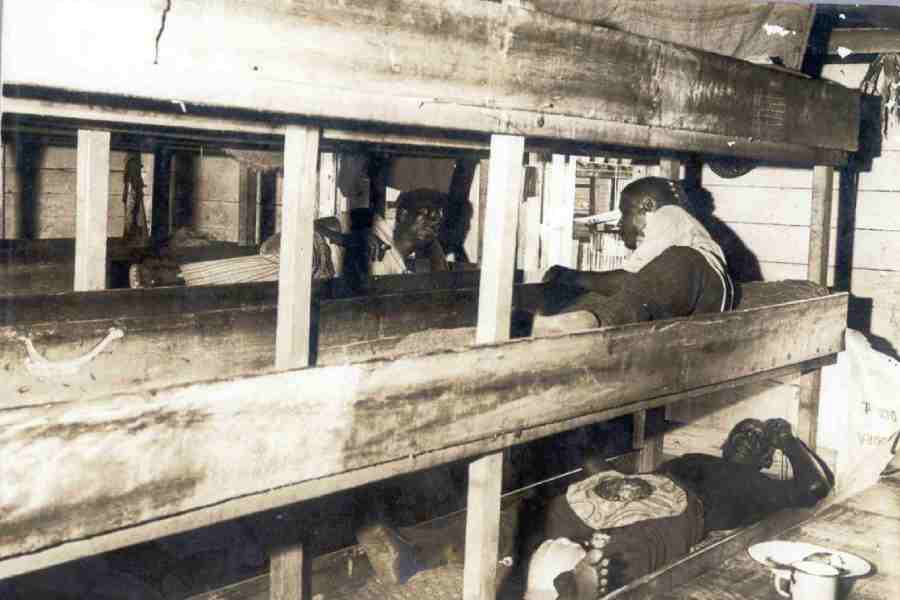

They arrived at the depot on D.L. Khan Road on foot and on bullock carts, and after 1854, when the railways were introduced, till Raniganj by train. They had to pass a fitness test, and in the morning they sailed by boat down Adi Ganga to the Hooghly where the ships were moored midstream. No landing stage or jetty existed then and sailing ships made of wood later gave way to iron vessels and steamers. There is a record of a woman carrying her two-month-old baby wading through the waters to board a ship. Many perished en route.

The entire stretch of the river witnessed the drama of deracination. The Indenture Memorial jetty and other memorials to the diaspora would never have come up without the tireless efforts of some enthusiasts like Leela Sarup and Sarita Budhu, whose husband was Deputy Prime Minister of Mauritius, added Gautam Chakraborti.

We arrived at the jetty late in the evening. The swirling waters of the river took on a darker shade. The memorial is simple. The clock tower, which allowed passing vessels to check the time, dates back to 1899. The absence of bright lights deepened the shadows.

In the gloom, the gurgling river seemed to give voice to the plight of the helpless humans shipped into the unknown from here. Their sighs and murmuring voices brought the murky past back to life again.